Review: Good Disagreement? Pt. 5, Pastoral Theology for Perplexing Topics: Paul and Adiaphora

I am continuing with my chapter-by-chapter, essay-by-essay review of Good Disagreement? Previously:

I am continuing with my chapter-by-chapter, essay-by-essay review of Good Disagreement? Previously:

- Part 1: Foreword by Justin Welby

- Part 2: Disagreeing with Grace by Andrew Atherstone and Andrew Goddard

- Part 3: Reconciliation in the New Testament by Ian Paul

- Part 4: Division and Discipline in the New Testament Church by Michael B. Thompson

N. T. Wright. Big fan. I’ve been exploring the depths of his perspective for some time now. In this contribution to Good Disagreement? he not only delivers his insights into the broader framework for conflict, he actually applies it to the issues at hand. Are sexual ethics a matter for indifference in the church? Wright’s answer is a resounding “no”.

Wright identifies a “double stress” in the current problems: an apparent tension between “unity” and “holiness.” For Wright this is only an appearance because “properly understood, they do not form a paradox, pulling in opposite directions… they actually reinforce one another.” (p67). I suspect those who would differ from him on sexual ethics would also resolve the tension; but for a different understanding of ‘holiness.’ The tension exists when there is need to agree to disagree.

For matters of adiaphora, (so-called “things indifferent), this tension is resolvable in charity – significant charity! Speaking of Paul’s appeal at the end of Romans, Wright offers:

He does not here ask the different groups to give up their practices; merely not to judge one another where differences exist. As Paul well knew (though we sometimes forget), this is actually just as large a step, if not larger, than a change in practice itself. …That is, of course, why the apparently innocuous “live and let live” proposals for reform are the real crunch, as most reforming groups know well. (pp76-77)

I love this summation of how the tensions of adiaphora are to be handled: “Messiah-people will make demands on one another’s charity; they must not make demands on one another’s conscience.” (p77). And similarly:

…the subtle rule of adiaphora is about as different from a modern doctrine of “tolerance” as can be imagined. “Tolerance” is not simply a low-grade version of “love”; in some senses, it is its opposite, as “tolerance” can imply a distancing, a wave from the other side of the street, rather than the rich embrace of “the sibling for whom the Messiah died. (p81)

I think I was saying something similar earlier about the danger of mere “conversation” being the stuff of theological strangers.

For issues that are not indifferent, the “live and let live” tension is simply not tenable. They are matters which define and undergird the unity, rather than those which are worked out in the charity of unity. On such matters the difference is not simply a tension, it is a chasm.

To discern, therefore, the scope of what is adiaphora we must come to where Wright begins, to his understanding of Paul’s “vision for the church.” Here we have straight-down-the-line New Perspectives ecclesiology. In fact, for those getting into the New Perspectives, this chapter is not a bad introduction. The detail does not need rehearsing here and he is explicit about his conclusions:

Certain things are indifferent because…

The divine intervention, as Paul saw it, unveiled in the messianic events concerning Jesus, was to create a single worldwide family; and therefore any practices that functioned as symbols dividing different ethnic groups could not be maintained as absolutes within this single family. (p70)

Certain things are not indifferent because…

This divine intervention…. was that this single family would… embody, represent, and carry forward the plan of “new creation”, the plan which had been the intention for Israel from the beginning; and that therefore any practices that belonged to the dehumanizing, anti-creation world of sin and death could likewise not be maintained within this new-creation family. (p70)

And this is where Wright picks his side.

Now, others would use these categories on their side. For some, I’m sure, the church’s traditional view of homosexuality is “dehumanizing” and therefore the correction of that through the blessing of same-sex relationships etc. is a matter of necessity, and is not adiaphora. Despite the protestations of some (I think particularly of Loveday Alexander’s declared intentions that I heard recently) it is clear that the current disagreements are much more than letting some getting on with what they want to do; it’s each side seeing the gospel denied in the other. I cannot see how, if “live and let live” is the outcome of the shared conversations, we will have done much more than prove the insipidity of the identity we have left in common.

Wright’s basis for his position enters right into that ecclesial identity, and the call on the church to embody both new covenant and new creation:

In terms of creation and new creation, the new creation retrieves and fulfils the intention for the original creation, in which the coming together of heaven and earth is reflected in the coming together of male and female. This vision of the original creative purpose was retained by Israel, the covenant people, the “bride” of YHWH, and the strong sexual ethic which resulted formed a noticeable mark of distinction between the Jewish people and the wider world. (p71)

Paul insists that the markers which distinguish Jew from Gentile are no longer relevant in the new, messianic dispensation; but the Jewish-style worship of the One God, and the human male/female life which reflects that creational monotheism, is radically reinforced. (p72)

The line he draws around the adiaphora clearly rebuts the tired argument by which critics of the church’s position play the “why aren’t you obeying the whole law?” card.

The differentiation he introduces has nothing to do with deciding that some parts of the Torah are good and to be retained (sexual ethics) and other parts are bad and to be abolished (food laws, circumcision and so on). That is not the point… Some parts of Torah – the parts which kept Israel separate from the Gentile world until the coming of the Messiah – have done their work and are now put to one side, not because they were bad but because they were good and have done their work. Other parts of Torah – the parts which pointed to the divine intention to renew the whole creation through Israel – are celebrated as being now at last within reach through Jesus and the Spirit. The old has passed away; all things have become new – and the “new” includes the triumphant and celebratory recovery of the original created intention, not least for male and female in marriage. (p74)

There can be no good disagreement if the scope of adiaphora cannot be agreed to. It is the very playing field upon which the charitable and constructive tussle of church life can occur. Wright has provided, here, a thorough and thoughtful determination of the shape of that playing field; but the very same things have also determined which side he is playing on. Those who “play on the other side” must also justify a field of play that is coherent with their position. The danger of course is that the conversation is then cross-purposed: to extend the metaphor to breaking point, one side turns up to play football on a football field, and the other turns up with rugby kit across town; by what rules do the two engage?

Or, with more precision, the ongoing problem is outlined by these concluded remarks from Wright. It’s a problem to which he offers no solution:

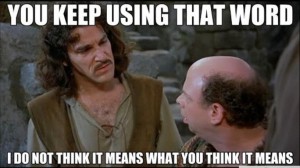

We of course, live in a world where, in the aftermath of the Enlightenment’s watering down of Reformation theology, many have reduced the faith to a set of abstract doctrines and a list of detached and apparently arbitrary rules, which “conservatives” then insist upon and “radicals” try to bend or merely ignore. It is this framework itself which we have got wrong, resulting in dialogues of the deaf, or worse, the lobbing of angry verbal hand grenades over walls of incomprehension. (p82)

Next: Part 6: Good Disagreement and the Reformation by Ashley Null

The conclusion

The conclusion In recent times many of us preachers have had our sermons recorded, turned into mp3s, and placed online. It doesn’t make us “internet preachers”, but it is the “tape ministry” of a previous decade in current form. It also means that, for better or worse, our homiletical efforts are recorded for posterity.

In recent times many of us preachers have had our sermons recorded, turned into mp3s, and placed online. It doesn’t make us “internet preachers”, but it is the “tape ministry” of a previous decade in current form. It also means that, for better or worse, our homiletical efforts are recorded for posterity.