Review: Good Disagreement? Pt. 10, Mediation and the Church’s Mission

I am continuing with my chapter-by-chapter, essay-by-essay review of Good Disagreement? Previously:

I am continuing with my chapter-by-chapter, essay-by-essay review of Good Disagreement? Previously:

- Part 1: Foreword by Justin Welby

- Part 2: Disagreeing with Grace by Andrew Atherstone and Andrew Goddard

- Part 3: Reconciliation in the New Testament by Ian Paul

- Part 4: Division and Discipline in the New Testament Church by Michael B. Thompson

- Part 5: Pastoral Theology for Perplexing Topics: Paul and Adiaphora by Tom Wright

- Part 6: Good Disagreement and the Reformation by Ashley Null

- Part 7: Ecumenical (Dis)agreements by Andrew Atherstone and Martin Davie

- Part 8: Good Disagreement between Religions by Toby Howarth

- Part 9: From Castles to Conversations by Lis Stoddard and Clare Hendy & Ministry in Samaria by Tory Baucum

We’ve arrived at the final chapter, and some final thoughts from me. This chapter is by former-barrister, now mediator, Stephen Ruttle. He gives us language to describe the current troubles, and a sense of how far or little we have come and are likely to go.

As a mediator Ruttle is, like many of the contributors to this book, a firm centrist. While he admits that this could include a propensity to avoid disagreement (p208) and sit on the fence, and while he recognises that he is not impartial on some theological or moral matters (p207), his presentation of mediation as “assisted peacemaking” (p195) after the way of Christ which makes it missional (p204) has great merit. For those who aspire to speak across the centre there is some wisdom to glean here.

Ruttle’s approach is strengthened by his realism about outcome and his focus on process:

“This chapter assumes that there are profound disagreements between Christians on important issues and that these disagreements are a fact of life which are unlikely to be resolved, at least in the sense that everyone will come to a common viewpoint. The questions that then arise are: How well can we disagree? Can we live together or not? If so, how closely? If not, can we separate with blessing rather than with cursing? Can we love each other despite these disagreements? How well can we “do unity”?” (p197)

In particular, his conception of “agreement” as being able to incorporate anything from full reconciliation to amicable separation means that his thoughts can be applied to the current troubles. If only “total agreement” is on the table, the conversation is already over. But if the ground under dispute is about good disagreement then there are things to talk about: honesty about the current situation, recognition of existing separation, re-connection where possible, honest exploration of faults and wounds, agreement about the extent of possible future separation, practical and symbolic implications etc. etc.

Similarly, his presentation of the mediation process is also insightful, and illuminates the current Shared Conversation strategy more than much of the rhetoric around them does. On page 213, he outlines the process as: “GOSPEL” – Ground rules… Opening Statements… Storytelling… Problem identification… Exploring possible solutions… Leading to agreement (p213). It’s a crazily complex situation of course, but from my observation the current process is passing through S (storytelling) and beginning to get honest about P (Problem identification). Many are much further on that that of course.

It’s still unclear what solutions and forms of agreement are possible in the current situation. Ruttle defines possible successes as (in order of depth):

A) Participation (p214); B) Ceasefire (p215); D) Resolution of the defining issue (p215); E) Resolution of the underlying issue (p215); F) Restitution (p215), G) Forgiveness (p216), H) Reconciliation (p216), I) Transformation (p216)

Depending on how “resolution” is defined and if “restitution” could incorporate some structural/institutional response to reduced common ground, I can see the possibility of a way through to G). This is further than what the cynic in me suggests is possible; and my caveats are deliberate!

This chapter also taps into some frustration. Ruttle gives some advice for participants in mediation to “step back” and work out the real issues, and to “slow down” (p209). Particles of wisdom such as these are already apparent, albeit chaotically. Many have “stepped back” over the years – we know what the issues are, and their epistemological underpinnings. And many have “slowed down” and persisted in meeting together through indabas and Covenant processes; the issue has been hot since 2003 and it’s cutting edge has been keen for many years before that. At some point there is also wisdom in not “drawing it out.”

Ruttle’s realism also connected with me on a personal level. As I read the following description I was recollecting the cost I counted at a particular time when I was the man in the middle.

It can be very lonely, marooned in the middle in a sort of no-man’s-land. I find myself increasingly stretched as I continue this work, particularly where I have my own opinions and judgments on the rightness and wrongness of the issues at take, or the people involved in the mediation. (p206)

The biggest difficulty in applying Ruttle’s words to the current circumstances, however, is this: who exactly is our mediator? We do not have a mere fracas between neighbours, or a financial dispute in which an impartial third-party can enter in. The issues at stake here are at the depths of a shared ecclesiology, our very identity and how it is expressed in following Christ.

It is here that Ruttle’s allusion to Christ’s mediatorial work breaks down a little. Yes, Jesus came to cross boundaries, and bring together former “enemies” (just read the first three chapters of Ephesians!). But he was not a mediator in the way Ruttle describes his work. Jesus also spoke, he spoke truth, and called us to follow him. He doesn’t pick sides, he defines the side.

And so this chapter brings us to the place where we have gone again and again in this book – the epistemological question: how do we know what Christ is saying? How do we seek God together? The only satisfactory direction – and what I hold is the Anglican direction – is to return to and come under Scripture, not merely locatively, but attitudinally. The extent to which we are unable to share in that posture is the extent of our troubles, and that is what we must deal with, and deal with it well.

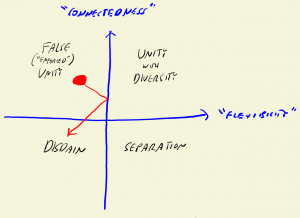

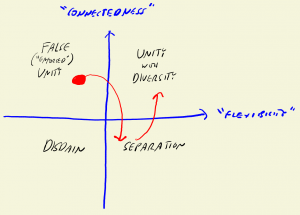

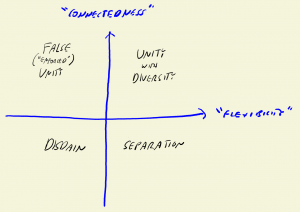

The framework loosely draws on the concepts of flexibility and connectedness. There are some marriage preparation courses that use these words to look at family of origin issues and modes of how people live together. I’m using them in a modified sense (and perhaps inaccurately) and applying them to ecclesial “family.”

The framework loosely draws on the concepts of flexibility and connectedness. There are some marriage preparation courses that use these words to look at family of origin issues and modes of how people live together. I’m using them in a modified sense (and perhaps inaccurately) and applying them to ecclesial “family.”