Unity, Diversity, and Conflict

I’ve adapted this from a talk I gave a number of years ago in my church-planting days. These were the heady days of the “mixed economy church” and, as a young gung-ho missional fresh-expressioner, I was asked to talk about how the church can draw together both the traditional and the contemporary. At the time, there was a degree of conflict between the “old” and the “new.”

I’m thinking about it now because of my current reading about the current issues of conflict. The current issues are epistemological and ethical, rather than missional, but there is still a correlation.

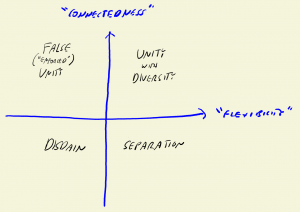

The framework loosely draws on the concepts of flexibility and connectedness. There are some marriage preparation courses that use these words to look at family of origin issues and modes of how people live together. I’m using them in a modified sense (and perhaps inaccurately) and applying them to ecclesial “family.”

The framework loosely draws on the concepts of flexibility and connectedness. There are some marriage preparation courses that use these words to look at family of origin issues and modes of how people live together. I’m using them in a modified sense (and perhaps inaccurately) and applying them to ecclesial “family.”

The ideal of course is in the upper-right quadrant. Unity is expressed not only institutionally but in true fellowship, and there is a diversity of expression in non-essentials that reveal the gospel in a fulsome and applicable way.

In the bottom-right quadrant we have low connectedness. There is a great deal of flexibility and freedom, and a full range of opinions exists, including much that reveals the gospel. Often these things are manifest independently and inefficiently. This is chaotic, but it can be creative, as we shall see.

In the bottom-left quadrant we have the worst of both worlds. There is low flexibility, but also low connectedness. The things that bind are more bureaucratic than anything else. At the same time differences are not well tolerated. This is a toxic situation marked by disdain.

The top-left quadrant has high connectedness, but low flexibility. This is not unity so much as uniformity and people are held together by some form of rigidity. This form of unity has a sense of compulsion, or at least obligation, and is therefore a false or “enforced” unity.

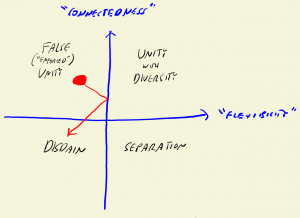

Conflict often lies in this top-left quadrant. Why? If there were less connectedness then the parties wouldn’t care about each other enough, or interact with each other enough, for the conflict to foment. If there were more flexibility then differences could be accommodated.

This is a possible way of looking at the current situation, which is manifest on matters of sexual ethics but actually runs deeper to fundamental matters of worldview. Anglicanism is still connected – at the very least (and it is much more than this) by an episcopacy, a shared geography, by history, and by formularies and legal standing. It is very clearly a broad church with a great deal of diversity of expression. But there is a point of inflexibility: an articulated, inherited, and (many would argue) necessary restriction on matters of doctrine and practice.

The rub of it is this. Conflict makes us insecure about unity. We therefore try and get to the happy quadrant of “unity and diversity” by emphasising what holds us together. But at this point unity and inflexibility are interlinked. We end up with paradoxical behaviour – we try and allow flexibility by inflexible means.

In my original context of missional expression this looked like diversity-by-management and showed the problem of “high control, low accountability” which brings new expressions to a painful and grinding halt. The attempt to get from the left-top quadrant directly to the right-top quadrant is therefore fraught. It’s a “hard wall” transition, and the likely result is a rebound to a worse situation in which both diversity and unity are diminished.

In my original context of missional expression this looked like diversity-by-management and showed the problem of “high control, low accountability” which brings new expressions to a painful and grinding halt. The attempt to get from the left-top quadrant directly to the right-top quadrant is therefore fraught. It’s a “hard wall” transition, and the likely result is a rebound to a worse situation in which both diversity and unity are diminished.

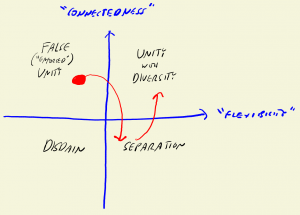

Rather, the road to “unity in diversity” is achieved more effectively by loosening the connectedness, and offering freedom, even a degree of separation. This allows room for the diversity to manifest itself. In the missional context, it gives space for a new expression to “find itself” in God, to work out its vision and communal life, and so be blessed.

Moreover, as the diversity grows, free of connectedness, there can be a discovery of things held in common. Upon this common ground a unity can be explored and expressed, resulting in a life-giving “unity in diversity.” Connectedness increases without reducing flexibility, and the result is good.

Moreover, as the diversity grows, free of connectedness, there can be a discovery of things held in common. Upon this common ground a unity can be explored and expressed, resulting in a life-giving “unity in diversity.” Connectedness increases without reducing flexibility, and the result is good.

In sum, the “conflict” is resolved by letting go, offering freedom, and then seeking to restore unity from a place of possible separation.

In the current troubles, I wonder if this is the shape of a way forward. Rather than grasping at unity, allow freedom, recognising that that freedom may include at least some element of separation. From that place of honesty and freedom, the common ground can then be re-explored, and expressed in a mutually appreciated way.

In recent times many of us preachers have had our sermons recorded, turned into mp3s, and placed online. It doesn’t make us “internet preachers”, but it is the “tape ministry” of a previous decade in current form. It also means that, for better or worse, our homiletical efforts are recorded for posterity.

In recent times many of us preachers have had our sermons recorded, turned into mp3s, and placed online. It doesn’t make us “internet preachers”, but it is the “tape ministry” of a previous decade in current form. It also means that, for better or worse, our homiletical efforts are recorded for posterity.