Richard Foster’s Prayer is a classic of the early ’90s but I’m glad that I have only just recently read it. I don’t think I would have truly understood it, or been impacted by it, if I had come to it before I’d lived some life.

Richard Foster’s Prayer is a classic of the early ’90s but I’m glad that I have only just recently read it. I don’t think I would have truly understood it, or been impacted by it, if I had come to it before I’d lived some life.

Foster is, of course, known for his teaching on spiritual disciplines with contemporary application. This book is in the same vein. It is a compendium of independent chapters, each considering the sorts of prayer that we see in the biblical narrative and in Christian experience. A quick look at the table of contents reveals the gist: “Simple Prayer, Prayer of the Forsaken, The Prayer of Examen, The Prayer of Tears, The Prayer of Relinquishiment…” and so on.

Foster takes us to the base foundation of spirituality, to the character of God himself. God is a God who speaks, and who listens, and who creates and restores the relationship between himself and his people. How we interact with him, i.e. how we pray, is the question that takes us into these depths. Like similar relational questions (e.g. “How do I speak and be closer to my husband, my wife, my child?”) the answer is both simple (“Just speak!”) and profoundly deep, even mysterious. Like all relational issues, it requires both deliberate action and humble response. Prayer is not something to “master, the way we master algebra or motor mechanics” (page 8), but “we come ‘underneath’, where we calmly and deliberately surrender control and become incompetent.”

As I record my thoughts here I am not going to touch on every chapter, but on those parts that have challenged me, taken me deeper, or have reminded me of the gracious permission I have, as a child of God, to come to him in prayer.

Prayer of the Forsaken.

It is right that Foster touchs on forsakenness early in the book. This sense, occasional or frequent, is part and parcel of the Christian experience; we feel as if we are praying to bronzed-over heavens, when everything would scream at us that God is absent. Foster has drawn on “old writers” to give me a new phrase, “Deus Absconditus – the God who is hidden” (page 17) for those times when God appears to have disappeared.

The prayer of the forsaken is the prayer of the pair on the road to Emmaus who stand with “downcast faces” because of their dashed hopes about the one who was “going to redeem Israel.” They walk with Jesus, but he is hidden from them. It is the prayer of Jonah in the belly of the whale. It is the prayer of David, and Jesus himself, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

Times of forsakenness are a given in the Christian pilgrimage of life. And they are necessary. They take us to the bedrock of God’s sovereign grace where we are stripped of any pretence that we might manipulate God in relationship or prayer.

That is the next thing that should be said about our sense of the absence of God, namely that we are entering into a living relationship that begins and develops in mutual freedom. God grants us perfect freedom because he desires creatures who freely choose to be in relationship with him. Through the Prayer of the Forsaken we are learning to give God the same freedom. Relationships of this kind can never be manipulated or forced. (Page 20)

Such seasons are seasons of refining that burn hot. We question ourselves, and “nagging questions assail us with a force they never had before” (Page 23)… “‘Is there any real meaning in the universe?’ ‘Does God really love me?'”

Through all of this, paradoxically, God is purifying our faith by threatening to destroy it. We are led to a profound and holy distrust of all superficial drives and human strivings. We know more deeply than ever before our capacity for infinite self-deception. Slowly we are being taken off vain securities and false allegiances. Our trust in all exterior and interior results is being shattered so that we can learn faith in God alone. Through our barrenness of sould God is producing detachment, humility, patience, perseverance. (Page 23)

In the last year we have experienced a sense of this forsakenness. One instructive experience stands out for me: At a summer festival in 2017, ironically surrounded by the joy and bustle of the worshipping people of God, we found ourselves in this dark place – a deep sense of being lonely, abandoned, forsaken. As I breathed and paced myself to get to the next workshop a leader approached me and gave me a word that had been impressed upon him as he saw me randomly within the crowd. What was that word of the Lord in the midst of emptiness, frailty, darkness, and lost hope? “God is saying, he is giving you the courage of a lion.” It broke me, I wept, and it was bitter. It was bitter, but right.

True courage rests not on ourselves, but on faith. The prayer of the forsaken takes us deeper yet; faith rests on trust.

When you are unable to put your spiritual life into drive, do not put it into reverse; put it into neutral… Trust is confidence in the character of God… I do not understand what God is doing or even where God is, but I know that he is out do me good.” This is trust. (Page 25)

We cry out to the infinite mercy of God. We learn that “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” finds its answer in “Into your hands, I commit my spirit.”

The Prayer of Relinquishment.

There is faithfulness in the simple prayer of petition, in which our needs are laid out before our Lord and provider. But I have noticed that this form of petition can actually play an opposite role; we often use it as a defense against the leading of the Spirit. We lay out our needs before God and say “Lord, bless us” with a heart that actually says “I am going this way. I am doing these things. Now do your part, God, and make them work.” We build self-reliant castles, and hold our petitionary facade as evidence of faithfulness.

I have noted this tendency in my own journey with Jesus, sometimes with a desperate internal monologue: “Look at these things, fix them, sort them, don’t let me fall! I’ve turned up to work, where are you?” In an era of church which is fundamentally performance-driven, and amongst my generation of church leaders who are so readily anxiety-driven, I have heard this insecure form of “prayer” echoed time and time again.

The prayer of relinquishment calls us away from this dysfunction. It is the spiritual equivalent of a trust exercise, or, as Foster describes, “a person falling into the arms of Jesus, with a thirst-quenching sense of ‘ahhh!'” (page 50). Yet while this “soul-satisfying rest” is the end result of the Prayer of Relinquishment, it is not the journey.

The journey is Gethsemane. It is “yet not my will but yours be done”, prayed not as a catch-all default at the end of a prayer, but as a positive deliberate choice to submit our plans, our desires, our lives to the will of God. “All of my ambitions, hopes and plans,” sings Robin Mark, “I surrender these into your hands.”

We pray. We struggle. We weep. We go back and forth, back and forth, weighing option after option. We pray again, struggle again, weep again. (Page 53)

Indeed, “relinquishment brings to us a priceless treasure: the crucifixion of the will.” (Page 55) Personally speaking, given my first name, I can almost take this literally! And it is a treasure. In many ways, the battle of the cross was won at Gethsemane; from this point in the garden, Jesus endures for the sake of the joy set before him.

There is death to the self-life. But there is also a releasing with hope… It means freedom from the self-sins: self-sufficiency, self-pity, self-absorption, self-abuse, self-aggrandizement, self-castigation, self-deception, self-exaltation, self-depreciation, self-indulgence, self-hatred and a host of others just like them. (Page 56)

The Prayer of Suffering

When the journey with Jesus takes us to fields of forsakenness, or roads of relinquishment, our prayer can bear substantial internal fruit; we grow spiritually and the path leads to maturity. But prayer is not all about introspection. As his book concludes, Foster’s focus becomes increasingly external, even missional. He turns to intercession, to what he calls “radical” prayer, and to a vision for church as missional community (Page 268) that the rest of us are only just starting to realise.

The prayer of suffering embraces the missional concept of incarnation. This is not to undermine, as some have taken it, the salvation-bringing incarnation of Jesus. Rather, it takes the character of God in Christ as a model for how we obey the Great Commission and are sent as Christ was sent.

Christ serves us not from above and beyond our condition, but from within it. And so Paul can speak of a participation in the afflictions of Christ as part and parcel of his participation in his mission. And Peter can extend that participation in both suffering and glory to his readers, and so to us. In this sense we talk about suffering as redemptive, the same sense in which confession, preaching, evangelism, and other forms of witness are redemptive. The prayer of suffering expresses it.

In redemptive suffering we stand with people in their sin and in their sorrow. There can be no sterile, arms-length purity. Their suffering is a messy business and we must be prepared to step smack into the middle of the mess. We are ‘crucified’ not just for others but with others. (Page 234)

This is a conscious shouldering of the sins and sorrows of others in order that they may be healed and given new life. George MacDonald notes, ‘The Son of God suffered unto the death, not that men might not suffer, but that their suffering might be like his.” (Page 238)

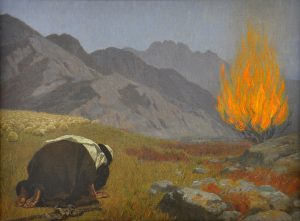

As Foster points out, (page 233), the concept of suffering is almost anathema to the consumerist culture of comfort that coerces conformity in the contemporary church. But this, itself, can create the redemptive suffering. Uncomfortable prophets and travailing intercessors are politely pushed aside or even directly silenced; their suffering and sorrow embodies the plight of the church and they cry out in the anguish of the church’s self-abuse. And so Jesus yearns for his Jerusalem and Moses refuses to give up the Golden-Calf-enslaved people of God:

‘I will go up to the LORD; perhaps I can make atonement for your sin’ (Exod. 32:30b). And this is exactly what he does, boldly standing between God and the people, arguing with God to withhold his hand of judgment. Listen to the next words Moses speaks: ‘But now, if you will only forgive their sin – but if not, blot me out of the book that you have written’ (Exod. 32:32). What a prayer! What a reckless, mediatorial, suffering prayer! It is exactly the kind of prayer in which we are privileged to participate. (Page 257)

What I have learned from Foster here is that this form of suffering is not only permitted, but valued in the dynamic of Jesus with his followers. In recent years I have come across many of the faithful who are have been all but submerged in the bloody mess that flows from the machinations of our religious organisations. I have come across the abused with their wounds flowing. I have witnessed the weary weeping of senior leaders overcome by the inertia of apathy. I have seen the delicate shells of those discounted, despised, condescended to and cut off by orphan-hearted panderers. I can count myself amongst both the wounding and the wounded.

The prayer of suffering turns this pain towards redemption. Daniel prays in the pain of exile, confessing the sins of those others that sent him there. Jesus, impaled by the nails of desperate human rebellion, prays for their forgiveness and Stephen later echoes him as the stones descend and Saul looks on. Their prayers availeth much, redeemeth much. They are prayers of suffering.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer says that when we pray for our enemies, ‘we are taking their distress and poverty, their guilt and perdition upon ourselves, and pleading to God for them. We are doing vicariously for them what they cannot do for themselves.’ (Page 240)

There is intimacy in this prayer, and it brings intimacy to our mission with Jesus. Only in intimacy can we pummel the chest of our heavenly Father, offering prayers of “holy violence to God” (Page 241). Only in intimacy can the accusatory cry of the martyrs, “How long, oh Lord?” find its answer in the divine heart.

This is not anger. It is not whining. It is, as Martin Luther puts it, ‘a continuous violent action of the spirit as it is lifted up to God’. We are engaging in serious business. Our prayers are important, having effect with God. We want God to know the earnestness of our heart. We beat on the doors of heaven because we want to be heard on high. We agonize. We cry out. We shout. We pray with sobs and tears. Our prayers become the groanings of a struggling faith. (Pages 241-242)

Foster has reminded us here that suffering can be redemptive and should be released, not suppressed, in prayer. It is not wrong to demand a divine audience. It is not wrong to be more persistent than the widow. It is entirely right to bring our cause before our righteous, just, and loving Father. Maybe our cause is unjust; he can meet us in our prayer and change our heart. But maybe it is true, and we have been unknowingly sharing the heart of God, who mourns with those who mourn, and is stirred to redemptive action.

Come, Lord Jesus.

Thanks for the question, Sarah. There’s a lot in here.

Thanks for the question, Sarah. There’s a lot in here.