Like churches themselves, there’s a tendency for those of us in pastoral ministry (ordained and lay) to become self-referential; the aim of a “good” pastor is just to be good at it, for some insipid definition of “good” and indistinct definition of “it.” As an older priest once told me when I was young and green when I asked about his aims in ministry, it was simply “to survive, Will, to survive.”

Like churches themselves, there’s a tendency for those of us in pastoral ministry (ordained and lay) to become self-referential; the aim of a “good” pastor is just to be good at it, for some insipid definition of “good” and indistinct definition of “it.” As an older priest once told me when I was young and green when I asked about his aims in ministry, it was simply “to survive, Will, to survive.”

I know what he means now. Sometimes the vocation becomes merely a lurch of survival from Sunday to Sunday on a merry-go-round of meetings and rotas. It can look like duty and diligence and all manner of virtuous things, but it’s hardly the stuff of a world-changing gospel.

All of us in ministry need an occasional reordering, a return to a sense of vocation that cuts across the self-referential malaise and gets us looking Jesus-ward again.

Vanhoozer’s and Strachan’s The Pastor as Public Theologian is a book for such a reordering. It aims to “reclaim a lost vision” and does so in a way that is not just timely but also (as Eugene Peterson claims on the cover) urgent. Personally speaking, it has been a long time since I have read a book throughout which I have exclaimed “Yes!” and “That’s right!” and “This! Absolutely this!”

The authors begin by decrying the tendency to dislocate theology from the work of on-the-ground ministry by relegating it to the academy. The separation of “practical” and “theological” is truly a false dichotomy. With my background in both Pentecostal and Reformed streams it’s one that I have flailed against. It is why I have sometimes described my framework for ministry as that of an “applied theologian.” Application and theology go together.

We are reminded that the straitjackets of this dichotomy are still prevalent. Expectations on the pastor take the shape of counsellor, business analyst, sociologist, manager, entertainer, or educator. It’s these expectations that creep into board meetings, “action planning,” and even (if they happen at all) times of prayer.

The book has been edited to include a number of short “pastoral perspective” chapters from other contributors. One of them, Gerhald Hiestand, wonderfully describes this malaise by recognising that pastors are often “swimming against the current of the atheological swamp that is contemporary evangelicalism.” (p29).

In this way, Vanhoozer and Strachan are not just writing to pastors, they are also writing to churches. The reordering they stimulate is not just about church leaders, but about the nature and shape of the church itself.

Theology is in exile and, as a result, the knowledge of God is in ecclesial eclipse. The promised land, the gathered people of God, has consequently come to resemble a parched land: a land of wasted opportunities that no longer cultivates disciples as it did in the past. (pp1-2)

We are writing to you, churches, because you need to be encouraged to rethink the nature, function, and qualifications of the pastors whom you appoint to serve you… We also think you need to reclaim your heritage as a theological community created by God’s Word, and sustained by God’s Spirit, and to remember that you are part of God’s story, not that God is part of your story (pastor-theologians ought to be able to help you with this!). (p2)

The key phrase used throughout is the double-barrelled “pastor-theologian.” It usefully interacts with their fundamental concerns about the false dichotomy. But it is an awkward phrase with no clear scriptural anchor point. There are some other words which might better serve the purpose.

For instance, the work of the “pastor-theologian” is the work of a missionary.

The word “missionary” has its own baggage, of course, but it makes clear that whenever Vanhoozer and Strachan describe a pastor-theologian in action, they actually end up dealing with missiological issues. They end up discussing the demonstration and application of the gospel in the shifting culture of the real world. This is necessarily theological work; how else do you apply the gospel but by first understanding it? And it is also countercultural work; how else do you apply the gospel but by finding the touchstone points where it pushes back and has something different to say?

Missionary language would have helped the authors as they show us the challenges of this work. Missionaries understand the difficulty of articulating and demonstrating the application of the gospel in the real world. They know that the countercultural gospel, when filled with the theological richness of Christ’s death and resurrection, will always be resisted, passively or otherwise.

Make no mistake: it is not easy to go against the cultural grain, and in a real sense, the faithful pastor will always be a countercultural figure: what else can pastors be when they proclaim Christ crucified and then ask disciples to imitate their Lord by dying to self? (p3)

The flock of Jesus Christ is threatened not by lions, bears, or wolves (1 Sam 17:34-35) but by false religion, incorrect doctrine, and ungodly practices – not to mention “principalities and powers” (Eph. 6:12 KJV). Consequently, pastors who want to be out ahead of the congregations must be grounded in the gospel and culturally competent. Public theologians help people understand the world in which they live and, what is more important, how to follow Christ in everyday as well as extraordinary situations. (p23)

In this aspect of pastor-theologian as missionary I particularly valued Melvin Tinker’s short contribution which is a missiological reflection with respect to the UK. Reflecting on a “Babylonian captivity” in English culture, he describes symptoms that I am coming across in my current context:

The nature of the “captivity” shows itself… by relativism in public and private ethics, valuing people by their looks and work, secularization with the marginalization of religion in public life (“privatization”). Taken together, the Christian certainly feels like an alien and is alienated. The gap between what is believed and how it can be practiced (without guidance) can reach cavernous proportions in people’s minds, and so the temptation to capitulate to the world by privatizing religion is strong. (p62)

Secondly, it would have been more helpful for “pastor-theologian” to be understood in terms of the five-fold ministry, and particularly with regard to the apostolic.

The five-fold ministry of Apostle, Prophet, Evangelist, Pastor and Teacher is unpacked by Paul in Ephesians 4. These are gifted roles which have the purpose of “building up the body” to maturity in Christ. Vanhoozer and Strachan explicitly apply the same function to the pastor-theologian who has the work of “growing persons, cultivating a people” (p125).

I would have thought it would have therefore been more helpful to interact closely with these five offices. Rather, although the teaching, pastoral, prophetic, and evangelistic work of the pastor-theologian are all teased out at one point or other, it is an implicit correlation.

Instead, they fill the phrase “pastor-theologian” theologically by exploring its ambassadorial nature which “participates” (p48) in the “prophet, priest and king” (p39) offices of Christ’s new covenant ministry. This is helpful, but in sum it most readily describes an apostolic form of ministry; the apostolic ministry is inherently representational of Christ (“as the Father sent me, so I send you”, John 20:21) and, in practice, informs, guides and demonstrates the missiological exercise of the other four.

Apostolic ministry is also marked by a kenotic (self-emptying) character that carries the church, in her suffering and adversity. This is a characteristic that Vanhoozer and Strachan pick up and apply to the “pastor-theologian”:

Here is the central paradox: the pastor is a public figure who must make himself nothing, who must speak not to attract attention to himself but rather to point away from himself – unlike most contemporary celebrities. The pastor must make truth claims to win people not to his own way of thinking but to God’s way. The pastor must succeed, not by increasing his own social status but, if need be, by decreasing it. (pp13-14)

The prophet did not generally minister from a position of earthly power but rather by entering into the people’s suffering. (p46)

The pastor images the old-covenant priest by modeling for the church a set-apart life. This righteous model is designed to inspire, edify, and if necessary critique the people – all for the sake of encouraging them to pursue the Lord with zeal so that they too may be transformed. The pastor is no more (or less) righteous than the people. Ministry does not scrub away personal imperfections and weaknesses, but rather magnifies them, drawing pastors to first lay claim to divine grace before ministering it to their people. (p51)

Pastoral leadership ought to march to the beat of a different world-defying drummer, participating in Christ’s kingship by personifying the cruciform wisdom of God. (p54)

In the end the authors rest the theological task (and hence its doxological, liturgical, didactic, and pastoral expressions) of the pastor-theologian on something fundamentally epistemological and Christ-centred. It is a “ministry of reality” (p108), a communication “in word and deed, in person and work, [of] the reality of the new resurrection order: the renewal of human being” (p107) and of culture. Whatever really is, is in Christ, and is therefore known in him.

There is a touching point for this in my own Anglican context. Vanhoozer and Strachan’s reordering of vocation brings us continually back to consider time again that which is in Christ. Our ministry is formed and shaped by what is in Christ because what is in Christ is fundamental reality, an epistemological fixed-point in space-time. Moreover, “Scripture alone provides an authoritative account of what is in Christ (p114).” A shared scriptural epistemology is therefore essential not only to the building up of the church (because what is in Christ is the rich common ground of true koinonia) but consequentially essential to the unity and collegiality of pastors themselves. As I have reflected on in other places, this is at the heart of current Anglican disagreements.

It is clear that I resonate with the vision that Vanhoozer and Strachan attempt to reclaim. After all, this blog is called “Journeyman,” which also alludes to a “jack-of-all-existential-trades” (p104) vocation! I’d be happy for that to mean for myself, to be “in some sense a public theologian, a peculiar sort of intellectual, a particular type of generalist.” (p15) I am with Kynes (another minor contributor to the book) who recognises that theology is not dead, but living. Its appeal is both affective and cognitive. It is “truth, goodness, and beauty” (p134).

This beauty excites me, it drives me to prayer. It lingers when I think of the society and community in which I am now placed. It is the beauty of our Saviour who gave himself for this world. It is the beauty of God’s rag-tag people. It is the beauty of the new life to which this world is called. It is worth a lifetime of effort.

One of the most important dynamics in living churches is that of intentional one-on-one relationships that help individuals mature in their faith. We have our Sunday gathered worship times, and our small groups, and prayer triplets and things like that, but intentional personal investment is invaluable. Many of us can reflect on the individuals who have invested in us over the years, be it formally or informally; they are invariably God’s gift to us.

One of the most important dynamics in living churches is that of intentional one-on-one relationships that help individuals mature in their faith. We have our Sunday gathered worship times, and our small groups, and prayer triplets and things like that, but intentional personal investment is invaluable. Many of us can reflect on the individuals who have invested in us over the years, be it formally or informally; they are invariably God’s gift to us.

Like churches themselves, there’s a tendency for those of us in pastoral ministry (ordained and lay) to become

Like churches themselves, there’s a tendency for those of us in pastoral ministry (ordained and lay) to become  I have learned that the Scottish love Scotland. And the Welsh love Wales. But do the English love England?

I have learned that the Scottish love Scotland. And the Welsh love Wales. But do the English love England? Gill and I had a wonderful opportunity to be in Canterbury last week. Canterbury Cathedral had made a “Canterbury Cross” for our former church,

Gill and I had a wonderful opportunity to be in Canterbury last week. Canterbury Cathedral had made a “Canterbury Cross” for our former church,

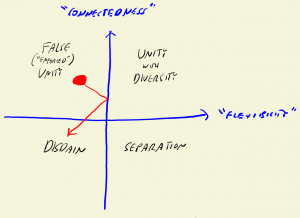

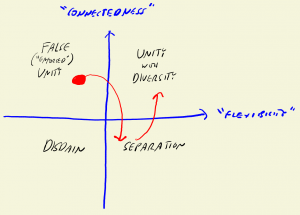

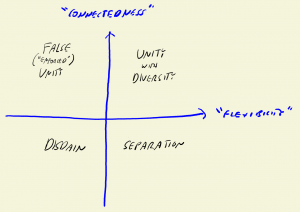

The framework loosely draws on the concepts of flexibility and connectedness. There are some marriage preparation courses that use these words to look at family of origin issues and modes of how people live together. I’m using them in a modified sense (and perhaps inaccurately) and applying them to ecclesial “family.”

The framework loosely draws on the concepts of flexibility and connectedness. There are some marriage preparation courses that use these words to look at family of origin issues and modes of how people live together. I’m using them in a modified sense (and perhaps inaccurately) and applying them to ecclesial “family.”