Missional Worship: A Mild Critique of the Five Marks of Mission

They came up in a discussion I was having recently: the so-called “Five Marks of Mission”, here taken from the Anglican Communion, in which they were developed over the last 30-40 years.

They came up in a discussion I was having recently: the so-called “Five Marks of Mission”, here taken from the Anglican Communion, in which they were developed over the last 30-40 years.

The mission of the Church is the mission of Christ:

1) To proclaim the Good News of the Kingdom

2) To teach, baptise and nurture new believers

3) To respond to human need by loving service

4) To transform unjust structures of society, to challenge violence of every kind and pursue peace and reconciliation

5) To strive to safeguard the integrity of creation, and sustain and renew the life of the earth

They are intended to “express the Anglican Communion’s common commitment to, and understanding of, God’s holistic and integral mission.” They’ve got a lot going for them.

They’re not perfect, of course. The Anglican Communion website recognises, for instance, that they don’t fit together like five equal parts.

The first Mark of Mission, identified with personal evangelism at the Anglican Consultative Council in 1984 (ACC-6) is a summary of what all mission is about, because it is based on Jesus’ own summary of his mission. This should be the key statement about everything we do in mission.

And this is a worthy observation. After all, you clearly can’t do 2) (teaching and nurturing) without also doing 1) (proclamation).

The last three are, in my mind, in a slightly different category, because they incorporate forms of activity in which the specific revelation of the gospel in Jesus is not entirely necessary. What I mean is this: It is conceptually impossible to proclaim the gospel of Jesus and nurture new believers in Jesus without actually having a faith in Jesus. However, it is possible to engage in loving service, transforming unjust structures, and renewing the life of the earth without knowing or speaking the name of Jesus.

This does not denigrate these last three. They are a necessary and important outworking of the gospel in the lives of Christians and Christian communities. Moreover, they are forms of mission where our cause overlaps with many other activists who do not follow Jesus. Not only are they achieving a good in their own right, they also facilitate the first two as we are provided with opportunities to give reason for the hope that we hold (1 Peter 3:15).

In many ways I applaud them. I love it when the church is moved to do, rather than to sit apathetically behind rose-colour stained glass windows. As the saying goes, “It’s not the the Church of God that has a mission in the world, it is the God of Mission who has a Church in the world.”

My critique of the Five Marks, then, is not about what they say, but what they don’t say. It’s more than omission, it’s like there’s something askew. It’s a slant that is often present in conversations about mission. I think of the “Mission Minded” tool that we used during my training years; in many ways it was excellent, but there was something missing. That tool outlined various activities that churches could be involved in, but there wasn’t a clear place for something that seemed crucial to church life. That something was worship. Where is the doxological character of Christian mission?

Christian mission, for it to be something deeper than “mere” activism, must be essentially worshipful.

After all, the “chief end of man”, as the Westminster Shorter Catechism states in its very first question is to “glorify God and enjoy him forever.” What an excellent definition of worship! The “chief end” is not the making of Christians and the bringing of justice (although they are necessary corollaries) it is to the glory of God.

The Catechism is not going out on a limb here. Jesus, himself, would have us pray “hallowed be your name” even before we pray “your kingdom come, your will be done.” The hallowing of God’s name is not just prior, it is integral to our seeking the kingdom and the will of God.

Similarly, the mission of Jesus is not essentially pragmatic but is rooted and immersed in the adoring, loving relationship between Messiah and God, Son and Heavenly Father.

Very truly I tell you, the Son can do nothing by himself; he can do only what he sees his Father doing, because whatever the Father does the Son also does. For the Father loves the Son and shows him all he does.

John 5:19-20

In the big-picture eschatological scope, the glory of God is also the chief point of mission. When Paul speaks to the Corinthians about the end of time, he speaks of Christ’s mission as “putting all his enemies under his feet,” and then submitting himself, and all that is under him (that is, everything!), to God his Father. Christ’s mission is to ensnare all of creation into his own worship of his eternal Father.

But Christ has indeed been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep. For since death came through a man, the resurrection of the dead comes also through a man. For as in Adam all die, so in Christ all will be made alive. But each in turn: Christ, the firstfruits; then, when he comes, those who belong to him. Then the end will come, when he hands over the kingdom to God the Father after he has destroyed all dominion, authority and power. For he must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. The last enemy to be destroyed is death. For he “has put everything under his feet.” Now when it says that “everything” has been put under him, it is clear that this does not include God himself, who put everything under Christ. When he has done this, then the Son himself will be made subject to him who put everything under him, so that God may be all in all.

1 Corinthians 15:20-28

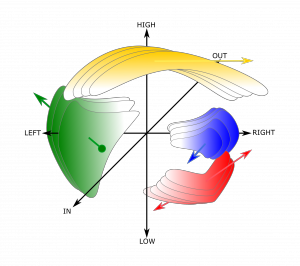

When I was young, I was moved towards activism. I was moved towards doing mission. In my zeal I misunderstood or even disparaged more “worshipful” aspects of our spirituality such as contemplation, adoration, and prophetic acts. At best, I used “quiet times” and “retreat days” as ways of stoking the fire for the “real work” of reaching people with the gospel or “building the church.” If I used the “up-in-out” triangle, my emphasis was on the “out.”

I was wrong. And I am not alone. The “up” must come first, because it is the heart of both the “in” and the “out.” Even now I run into situations where there is a false dichotomy between “worship” and “mission.” If there is a separation between doing the “work of God”, “drawing people to God”, and “adoring and worshipping God” then, frankly, we’re doing it wrong!

One of my greatest concerns for the contemporary Western church is our entrepreneuralism. When that speaks of innovation and focused pursuit of the gospel, I cheer it on. But sometimes it lapses into pragmatism, or even task-oriented rationalism, and, more often than we might care to realise, self-glorification. When we are at risk of asserting control for the sake of our own existence or empowerment, even as we pursue the five marks of mission, we risk losing the way of faith. We must return to worship, attuned to a King who will bring all things under the father at the end, by being a living sacrifice now, hallowing his name. That is the chief mark of mission – to glorify God.

We are encountering, more than we ever have, a growing number of people who are moved to worship. Sometimes it is through prayer and intercession; they travail, literally groaning as they filled with the Spirit. Sometimes they adore, and rest, and exhibit the peace, sometimes ecstasy, of that very same Spirit. Sometimes they offer words of knowledge and wisdom, speaking prophetic truths that do what all prophetic truths do; they call us back to hallowed ground where Father’s name is all in all.

Many (but not all) of these feel homeless in today’s church. They feel tangential to the missional machine, un-embraced and unreleased, because the missional return on investing in them is not clear to a “missional church.” Yet, I am fully convinced, without their leadership, we have lost our way. Without their heart, we can do “our” mission, and find on the last day that we already had our reward.

This is not a new thing. And I’m not trying to paint a black picture. Different traditions have the tools to do the recalibration of mission around the heart of worship. The Catholic propensity to interweave mission and the eucharist encapsulates, at the very least, the missional value of simply bringing the presence of God to where it is needed and administering his grace. The Charismatic and Pentecostal world values times of “worship and ministry” as a place where the Holy Spirit administers healing, revelation, acceptance, and conviction; a space into which Christian and non-Christian like can be invited. The Liberal claim to self-effacement, to be followers of the Word rather than asserting ourselves, can line up with this. And the Evangelical posture of submission to the Word of God in all things, for its own sake, takes us to where we need to be.

For myself, as I think about mission in my own context, and have found myself being led by worshippers: Let us first turn our face to our Heavenly Father. Let our hearts and our very beings resonate in adoration. Let us cry “Holy Holy Holy” with the choir of heaven. The chief mark of mission is to glorify God, who made heaven and earth.

Thanks Sarah. An interesting question. Allow me to answer it generally, and then more specifically.

Thanks Sarah. An interesting question. Allow me to answer it generally, and then more specifically.