Q&A: Do you believe that the earth is 6000 years old?

Anonymous asks: do you believe that the earth is 6000 years old?

Oh, at least that. 😀

See my previous answer concerning evolution: here

Wild attempts at thinking things through.

Anonymous asks: do you believe that the earth is 6000 years old?

Oh, at least that. 😀

See my previous answer concerning evolution: here

Anonymous asks: Can you explain Ezekiel 30:10-11 and how it was fullfilled? because from what i could find Nebucanezzar failed to conquer Egypt

I am not an OT scholar! I would make the following points.

Those are my initial thoughts. Feel free to push back in comments (not Q&A) below.

Anonymous asks: do you anwser every question from the Q&A that is given to you?

Pretty much. Some Q&A questions are really actually comments for a post. In those cases I repost the question as a comment. Occasionally I get some spam. But yep, I answer all Q&A that I get.

W.

It takes a special book to capture my imagination. There are plenty of books that stimulate my thinking or tickle me with trivia. The occasional epic novel moves me with allegory, symbolism, and a decent hit of adrenaline. But these are nothing when it comes to a decently written biography, particularly an autobiography.

It takes a special book to capture my imagination. There are plenty of books that stimulate my thinking or tickle me with trivia. The occasional epic novel moves me with allegory, symbolism, and a decent hit of adrenaline. But these are nothing when it comes to a decently written biography, particularly an autobiography.

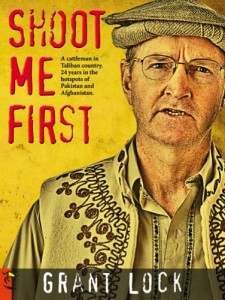

Grant Lock’s Shoot Me First is a decently written autobiography.

Grant, and his wife Janna, have worked for 24 years in “the hotspots of Pakistan and Afghanistan” – both before and after 9/11. In Shoot Me First we walk with Grant and Janna through a life of foreign aid work done properly – not from some air-conditioned hotel, but in the dust and dirt, learning the language, embedded in the culture. The sense of the difficulty is palpable – from the aridity of the climate, to the awkwardness of being new to the culture, to having their children away at boarding school, to the frustration with systemic corruption. But this is mixed with a genuine sense of love and purpose and determination so that it all comes across with a poignant reality.

The title of the book derives from a particular event in which the workers Grant was leading in building a school for women in Pakistan were threatened with violence. Grant stood in the breach – “You’ll have to shoot me first!” – and then recounts the hours of working through the nuances and complexities of human culture and human pride so that the project could proceed.

This book doesn’t just give an insight into a couple and their life, it gives insight into a region, a people, and a culture that is so vitally linked to the machinations of world politics. It’s one of the reasons why we were delighted to have Grant speak at St. David Cathedral’s Friday Forum on the topic of Afghanistan and Islam and it’s implications for Australia.

Grant has therefore positioned himself as a valuable voice for our society. The years of service demonstrates that he has put his money, and time, and effort, and pain where his mouth is when it comes to loving and building a people. He can dissect Islam the religion, from Islamic cultures, and give critiques of both that are informed and relevant.

It is therefore useful that he leaves it to near the end to build his commentary. He does this by recounting conversations. The first is with his son, discussing the problems of the region and the reason to keep on keeping on.

Matt takes a deep breath and exhales. “Doesn’t it make you feel like you ought to just pack up and go home, Dad?”

“Occasionally, Matt.” Another plate of sizzling kebabs appears on our table. “But when I see the delight of an old lady getting her first glasses, or Afghans we’ve trained building micro-hydroelectricity plants for mountain villagers, or Janna’s embroidery widows making a go of it, I just want to be here to be part of it all. There’s a local saying: Qatra qatra, daryaa mehsha.”

“Which means?”

“Drop by drop a river is made.” (Page 331)

The second is with his wife, where he talks about Islam in the West

“You know, Janna, after years of living in this part of the world, when I hear Islam being promoted as a religion of peace and freedom, I cringe… Australians should value what they have, keep their brains in gear and not believe everything without checking it out. They should understand that Islam is more that a religion. They should love and respect Australian Muslims, but they should be very alert in case, over a period of time, what they have is compromised by making gradual exceptions for a particular group in society”…

“You know, Grant,” Janna says, “if you expressed these views for the benefit of Australians, you would probably be labelled Islamaphobic by some Muslims.”

“That would just prove my point. It would show that they are not open to freedom of speech, and it would again raise the question: what is it about Islam, or any similar group, that it can’t handle open discussion?”

I didn’t have any trouble doing so, but if you pick up this book make sure you read it to the end. Much of the last part is made up of the story of a person called Omar. I wondered at the purpose of emphasising this story until I realised – Grant is using this story as a story of hope. For him, Omar represents this difficult part of the world, it’s destitution and deprivation, but also it’s eventual hope.

“Evangelical Universalism” – an intriguing theological framework It’s “universalism” because it’s a belief that all will eventually be “saved.” It’s “evangelical” because unlike other forms of universalism it maintains that Christ is the one and only way to salvation, and does not deny the authority of Scripture. On the face of it, it seems to be oxymoronic. But someone who strikes me as thoughtful challenged me to read the book, and so I did. Some time ago actually, but things have been busy.

“Evangelical Universalism” – an intriguing theological framework It’s “universalism” because it’s a belief that all will eventually be “saved.” It’s “evangelical” because unlike other forms of universalism it maintains that Christ is the one and only way to salvation, and does not deny the authority of Scripture. On the face of it, it seems to be oxymoronic. But someone who strikes me as thoughtful challenged me to read the book, and so I did. Some time ago actually, but things have been busy.

MacDonald writes well, with an appropriate studiousness and humility. My views are sympathetic with annihilationism and much of his arguments against the “traditional view” presuppose eternal torment and I approached my read with this in mind.

His introduction outlines his personal motivations in studying the topic. In many ways it is a basic theodical angst:

“The problem was that over a period of months I had become convinced that God could save everyone if he wanted to, and yet I also believed that the Bible taught that he would not. But, I reasoned, if he loved them, surely he would save them; and thus my doxological crisis grew. Perhaps the Calvinists were right – God could save everyone if he wanted to, but he does not want to. He loves the elect with saving love but not so the reprobate… Could I love a God who could rescue everyone but chose not to?… I longer loved God because he seemed diminished. I cannot express how deeply distressing this was for me…” (Page 2)

From this point he moves on to some more detailed philosophical considerations and then some exegetical considerations which he hopes will allow “universalist theology… to count as biblical.”

MacDonald exhibits some hermeneutical depth, drawing on Thomas Talbott he is honest about his assumptions:

“Talbott asks us to consider three propositions:

1. It is God’s redemptive purpose for the world (and therefore his will) to reconcile all sinners to himself.

2. It is within God’s power to achieve his redemptive purpose for the world.

3. Some sinners will never be reconciled to God, and God will therefore either consign them to a place of eternal punishment, from which there will be no hope of escape, or put them out of existence all together.

Now, this set of propositions is inconsistent in that it is impossible to believe all three of them at the same time…

Universalists thus have to reinterpret the hell texts. But they are in a situation no different from Calvinists or Arminians in this repect. ‘Every reflective Christian who takes a stand with respect to our three propositions must reject a proposition for which there is at least some prima facie biblical support.” (Page 37, 38)

And he brings a decent biblical theology to bear. Consider the diagram on Page 77 and also 105, which pretty much sums up his third and fourth chapters, that correlates crucifixion->resurrection of Christ to Israel’s exile -> return (via the suffering servant) to the fall -> (universal, in his view) restoration of humanity. This also gives a decent missiological ecclesiology:

“Thus, the church is seen as an anticipation in the present age of a future salvation for Israel and the nations in the new age. This, in a nutshell, is the evangelical universalist vision I defend.” (Page 105)

It is clear through all this that his motivations and arguments are, indeed, evangelical, even if we may question his conclusions.

It is somewhat difficult to argue against him as he does a great deal to argue that a number of theological frameworks (Calvinism, Molinism…) are compatible with universalism. So what framework do I use in any rejoinder? He could always escape into a different framework. Nevertheless, my concerns include:

1) A view of hell as mere purgatory. Apart from anything else, this quantifies grace. Some receive enough grace to be saved in this life, some need grace extended into the afterlife. In his appeal to the omnibenevolent God that makes hell redemptive, one could simply ask why the omnibenevolent God invokes hell at all and simply saves everyone forthwith, or, if there must be pain, through trials and revelations of truth in this life. Some form of hell must be invoked to maintain biblical warrant, but seems superfluous in a universalist framework.

2) Where does the universalism end? If all humanity is restored, then given his hermeneutical framework, all creation is restored. Does this mean salvation, say, for the devil and the demonic cohort, who are creatures? I didn’t see him deal with this but it raises significant questions both exegetically and theologically.

3) What does it do with our kerygma? While MacDonald usefully ties ecclesiology to soteriology, in application and proclamation he runs into difficulties in his framework. He says, drawing from Colossians, that “the Church must live by gospel standards and proclaim its gospel message so that the world will come to share in the saving work of Christ” (Page 52). But by his framework, this mode of proclamation is arbitrary and contingent – it will presumably finish, incomplete, at the day of judgement. Unless of course the redemption in hell is also done through the proclamation of the church but then we really are stretching into conjecture.

4) There are times when I think he mishandles corporate/individual salvation. His transition into considering Abrahamic covenant as a transition from nation to individual is too simplistic (Page 55). His desire to undermine categorical understandings of salvation for “all people” in Romans 5 ignores the context of Jew/Gentile categories (Page 83). Perhaps he has a need to extract individuals from the judgement on nations (and vice versa), but this again stretches into conjecture.

In the end, however, my problem comes down to “how would I preach this?” And the answer is, I don’t think I could. The finality of judgement is what gives us the impetus to cry “Maranatha”, it’s what energises our nurture as we provoke one another “all the more as we see the Day approaching”, it’s what stimulates our mission so that the Son of Man may find active lively faith on earth when he returns. These are activities, yearnings, longings, directions, purposes that inherently and rightly belong to this Kingdom, this age. To belay any aspect of these things to another mode of redemption appears antagonistic to the whole gospel imperative.

I agree with his theodical concerns. His hermeneutical critique has some merit. But if I must choose which framework to use I would still lean towards annihilationism as that which best encapsulates the biblical revelation.

This is a well written book. It does not dishonour Scripture. It is not intended to undermine the Christian gospel. It is worth engaging with. But in the end it takes us to places that are unwarranted and unhelpful.

Anonymous asks: does the anglican church believe rhat praying to saints is okay, because i seem to get rather contradictory answers….

No we don’t. One of our defining formularies is the 39 Articles and Article 22 states:

The Romish Doctrine concerning Purgatory, Pardons, Worshipping and Adoration, as well of Images as of Reliques, and also invocation of Saints, is a fond thing vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of Scripture, but rather repugnant to the Word of God.

Which pretty much sums it up really. If God is not the object of our prayers, and the agent of our prayers, then we are asserting that we can reach out to God in our own strength, or through the strength of someone else. This undermines the work of Christ and suggests that we do not have absolute need of him – something that goes against the heart of the Christian faith. Christ alone is our mediator.

We do respect the “Saints” as particular exemplars of the faith and count them amongst the “church triumphant” – but we count them as forebears – brothers and sisters in service, not the captains that we follow.

If you are being affected, or have been affected, by a long wait for surgery in the Tasmanian Health System consider joining the Waiting List Tasmania facebook group. It’s a place to share your story and raise your voice.

Delayed surgery is a situation felt by many. It affects not only the person who needs surgery but their friends and family.

Let’s talk to each other and encourage one another. Maybe we’ll get noticed.

Antionin asks: Do you believe that there are contradictions or errors in the Bible

Hi Antionin,

Thanks for the question. It depends what you mean by “contradictions” or “errors.” Your question interacts with the nature and communication of truth, which is not always simplistically propositional.

For instance in Job 38:4-7 we read

“Where were you when I laid the earth’s foundation?

Tell me, if you understand.

Who marked off its dimensions? Surely you know!

Who stretched a measuring line across it?

On what were its footings set,

or who laid its cornerstone —

while the morning stars sang together

and all the angels shouted for joy?

I assert that this paragraph is true. Yet it is ‘false’ and “in error” in some literal sense: Surely the earth does not have literal cornerstones and foundations; surely God did not use an actual measuring line! Yet the intention of this passage is clear and it is achieved – Job’s finitude in comparison to God’s magnitude is thoroughly and effectively communicated.

It is for this reason that I personally prefer to use the term “infallibility” when referring to the veracity of the Bible. It’s an imprecise term which some use to water things down to mean that Scripture is only true when it needs to be. I don’t mean it like that. I mean that Scripture always communicates truth, it achieves what it needs to be achieved, and this is infallibly true.

As for contradictions, it is hard to respond without specific examples to consider. Most of those that I have googled for usually end up at imprecision in language (or translation), different-perspectives on the same thing that aren’t actually contradictory, or forcing one part of the Bible to speak to the context of another part. Even the most famous “contradiction” of the supposedly irreconcilable resurrection accounts can be analysed using these sorts of concepts. (I’ve had a quick look at this page and it seems to be a good example)

So to answer your question, in the sense that I’ve outlined, I do not believer that there are errors or contradictions in the Bible.

Anonymous asks: When do you think the rapture will happen than? There are now wars and rumors of war (IRAN), we will not know the day or the hour, but we will know the season. Is fall 2012 the season?

Yes, absolutely, autumn 2012 is the season. And so was winter 2011, and spring of 1804, and, and…. pick a random date. We have been in the end times for approximately 2000 years and there has never failed to be wars and rumours of wars. Every war or rumour that occurs is a testimony that we are living in an age where the work of Christ’s faithfulness must, in faith, be exercised.

I don’t care when the rapture will or if it will happen. How will the answer to that help me fulfil God’s purpose for my life? I suspect those who are still living will meet Christ “in the sky” somehow to welcome him to his eternal kingdom. But in the meantime I will continue to worship him in every part of my life, whether it be planting a tree or writing a sermon, sharing fellowship in my church or drinking coffee with a new-found friend; with all my strength and by the love of Christ doing justice, loving mercy and walking humbly with my God.

Arguments about eschatological precision have always struck me as useless and vain controversies – they have no relevance to the real world! The Scriptures assures me that his kingdom will come on earth as it is in heaven and so I will continue to pray that prayer and work that work with a sure and certain hope. That is enough.

waffleater asks: what do you think about charsmatic visions like this one http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pVyMPqvnw5k do you believe in these gifts or not

Thanks for the question Waffleeater:

I’ll embed the video you link for ease of access:

It’s interesting. I haven’t heard of Unity before. Your question is a general one – what do I think about charismatic visions like this one and do I believe in these gifts or not.

Let me answer generally, therefore. I do believe that God gifts his church with visions and revelations at times. Some examples in Scripture of such “extra-biblical revelation” include Agabus’ foreknowledge of a famine (Acts 11) as well as through a prophetic symbolic act regarding Paul’s likely imprisonment in Jerusalem (Acts 21). Paul himself had dreams that directed his movements (the famous “Man from Macedonia” in Acts 16). None of this is surprising in that the fulfillment of Joel (“Your young men will see visions, your old men will dream dreams”) is applied to the church in and through the outpouring of the Spirit at Pentecost.

I know a number of people who have had similar experiences in their own ministry and mission work. I myself have had times of overwhelming conviction in certain circumstances. Surely this form of revelation/understanding/awareness/knowledge, whatever you would like to call it, can be a genuine and credible part of the Christian walk.

A key characteristic, however, is that revelations of this type are always SERVANTS of God’s clear and authoritative Revelation of himself through the Scriptures and its revelation of Jesus. If you like, the benefit of these forms of (little-r) revelation is that they help apply the (big-R) Revelation to a particular time and place. So the people of God can respond to the famine, Paul can be directed to Macedonia, and so forth.

I am ready to accept the revelations people experience from their walk with God – but they will always be tested by Scripture, and should always be a means of applying or grasping further the authoritative Truth of God.

Having said all that – let me consider Unity’s vision. It is interesting in that it is a broad statement with very little specifics. It draws on biblical imagery from Revelation 13 and Matthew 25. It does very little, however, to help us apply those Scriptures. In many ways my conclusion would be “Why do we need this vision at all? Reading Revelation 13 and Matthew 25 directly would be a lot more powerful.”

But, bring on revival in Australia. I can admire that sentiment.