Review: Theology of the Body for Beginners – Rediscovering the Meaning of Life, Love, Sex, and Gender

It’s not often that I encounter a book that is both intellectually and emotionally stimulating. I picked up Christopher West’s Theology of the Body for Beginners as background reading for some upcoming conversations about sexuality in the Church of England. What I encountered were some deeper insights. This isn’t really a book about sex and stuff, it’s a book about the stars; it beholds God’s grand narrative intimately and deeply and with no loss to its grandeur.

It’s not often that I encounter a book that is both intellectually and emotionally stimulating. I picked up Christopher West’s Theology of the Body for Beginners as background reading for some upcoming conversations about sexuality in the Church of England. What I encountered were some deeper insights. This isn’t really a book about sex and stuff, it’s a book about the stars; it beholds God’s grand narrative intimately and deeply and with no loss to its grandeur.

For better or worse, it is thoroughly Roman Catholic. The reason it is “for beginners” is because “Theology of the Body” is actually John Paul II’s opus. This book is Christopher West’s commentary on that work. Some caveats are therefore necessary; it is Catholic, and sometimes that is jarring. The mention of Joseph and Mary’s supposed perpetual virginity, and the censuring of contraception are two cases in point. These assertions, however, are mostly tangential to the essence of West’s argument, which remains worthwhile.

I found myself exploring the content in two aspects – personally and eschatologically – and two applications – individually and ecclesiastically. They are all intertwined, and it can be a confronting exercise.

For myself, when it comes to the personal aspect, I am quite familiar with my body. Over time, I have learned to listen to it. This is partly because as I’ve got older I’ve had afflictions, such as bladder cancer, which require me to pay attention. But mostly it’s because I am also familiar with anxiety. I know when the “fight or flight” adrenaline response kicks in, and when the knot in my stomach firms its grip. I am acutely aware when physical and existential angst overlap. I have experienced surgery trauma during a delicately intimate emergency procedure. I have also experienced, in my time, ecclesiastical mistreatment. Somehow my body conflates them and remembers both as a form of violation.

When it comes to the eschatological aspect, my engagement is this: I’m old enough to look back at my virile youth when zeal was pumping through my veins. Dreams and longings fizzed and popped. I would lie awake at night, not only moved by the prospect of juvenile romances, but by the sheer abundance of life ahead. I had idealism, expectation, and a simple desire for life. But it’s one thing to dream, it’s another thing entirely to pursue life “in the flesh.” It’s one thing to fantasize about a romance, and even act it out with someone else, exploring each other physically like adventurers on the brink of a new world. It’s another thing to bring those dreams, and those romances, into steady, stable, committed, reality. Our bodies get spent in the pursuit of life, yet that deep foundational desire is still in there. Belief, when manifest in the physical world, takes the form of desire; we long to desire life, and for life to desire us.

My question of myself, then, is how do I process this experience? How do I process it theologically? Abstractions and metaphor have their place, but it comes down to something physical: How am I loved by God? Me, in this failing, hurting flesh? Me, a fallen man. Am I safe with him? Does he love me in this fat, old, pale, body of mine? Will he be there for me when me and mine need him, literally?

And what about this church that I’m a part of? If we are, together, the Bride of Christ, then I can imagine us looking wistfully in the mirror, studying ourselves with a degree of shame. Perhaps there is torpid obesity, self-afflicted wounds dividing one member from the next, a hacking sickness as yet another abusive leader lodges like phlegm in our lungs. Are we abandoned? Can we ever be fruitful? Who are we that He, our Saviour, should desire us? In our own internal monologue, we speak to each other as if Jesus isn’t even in the room. Shared belief, when manifest in the ecclesiastical world, eventually boils down to desire, and therefore worship.

Do we trust that he loves us? Do we entrust ourselves to him? Forget about strategic plans and all the other church fippery; that’s what it comes down to in the end.

This is why a theology of the body is important. It touches us deeply, intimately, powerfully – both individually and collectively. This part of theology brings implications for all the hot-topic issues; it is why I was reading the book. But those topics are touchstones for a reason. They touch places that run very, very, deep.

No wonder we are all so interested in sex. God put an innate desire in every human being to want to understand the meaning of our creation as male and female and our call to union. Why? To lead us to him. But beware of the counterfeits! Because sex is meant to launch us toward heaven, the enemy attacks right there. When our God-given curiosity about sex is not met with the “great mystery” of the divine plan, we inevitably fall, in one way or another, for the counterplan. In other words, when our desire to understand the body and sexuality is not met with the truth, we inevitably fall for the lies…

(Page 108)

What West has encouraged me to do is to not shy away from words such as “erotic” when framing concepts of God’s love and mission. For many of us, “erotic” is a difficult word to talk about, and antithetical to anything divine. Eros often connotes uncontrolled passion, lustfulness, or a desire to dominate or manipulate. But we’re talking pure or redeemed eros here. It speaks of yearning and longing and of a form of love that is physically manifest. “Capital ‘E’ Eros – the very fire of God’s love – this is where small ‘e’ eros, the fire within each of us – is meant to lead.” (page 120). The incarnation teaches us that Jesus came in the flesh, and the defining act of “God so loved the world” was “This is my body, broken for you.” Eros is not something that taints the divine, it is the divine that defines and confines the fire of eros, and is its only satisfying end.

This maddening ache I felt inside was a yearning for the infinite, and God put it there to lead me to him… Christ doesn’t want us to repress our desires, he wants to redeem our desires – to heal them, to redirect them toward an infinite banquet of love and ecstatic bliss called “the marriage feast of the Lamb” (Revelation 19.9). Discovering this set me on fire!

(Page 3)

Therefore “the body is not only biological… [it] is also theological”, West says (page 11), and he is right. Indeed, “Ours is an enfleshed religion, and we must be very careful never to un-flesh it” (page 13). When we respond to Jesus, we don’t merely give intellectual assent, but a physical response. Not only do we “come to the altar” or wash our bodies with the waters of baptism, our very selves become his. To belong to Christ is to re-orient our physical selves, our yearnings, our longings, our actions, our sufferings. Collectively and individually we respond to his perfect and holy desire for us.

It doesn’t take too long for this to hit close to home. There were times when I had to put this book down because I was manifesting, physically, some of my traumas. I curled up in a ball. I felt, in my gut, the familiar knot of the unlovable, rejected, and ostracised teenager. I felt lonely; shallow-breathed, wild-eyed, scared, hiding my nakedness. I was being reminded that I want God’s love as more than theory; I long to know that the me-in-my-body is longed for, cared for, valued.

As I dared to dwell in this, I found the answer in the physicality of the cross. There have been times – very few times if I’m honest – when, as a man, I have expressed love by serving to the point of physical pain. But Jesus on the cross exemplifies such love. His love for me, for us, is leg-trembling, blood-sweating, shallowed-breathing, pain-moaningly clear. He loves me with his body; it is tenderness, it is affection, it is embrace. His touch on my life may be scary and frightening at times; but in his arms, I am safe, and I can surrender to him and bear much fruit to his glory.

But, to be honest, I struggle with those words. I’ve tried, and failed, to avoid sexual imagery. West’s encouragement is to not avoid it, but to find the holy foundations on which it is grounded. “In Christ eros is ‘supremely ennobled… so purified as to become one with agape‘” (page 23). There are two foundations that help us:

The first foundation is our own physicality. In the Genesis accounts God creates humanity with physical, sexed, bodies – male and female. Of course, in this current moment of trans and gender militancy, this is a difficult topic, and there is a complexity of “lived experience” to pay heed to. Nevertheless, the essential link between biblical ontology and physical sex is powerful and essential. It can’t be eradicated without fundamentally shifting how we conceive of God, and of ourselves. We are made in the image of God, and that includes our physicality. “God inscribed this vocation to love as he loves right in our bodies by creating us male and female and calling us to become ‘one flesh'” (page 12) and so to “fruitful communion” (page 18).

The second foundation is the so-called “spousal analogy.” Here is the coherence between marital union and the union of Christ and the Church. It is epitomised in Ephesians 5:25-33. And despite the misrepresentation of its detractors, it was also the substance of the recent CEEC video The Beautiful Story. West writes, “from beginning to end, in the mysteries of our creation, fall, and redemption, the Bible tells a nuptial, or marital, story” (page 21).

That’s where we can ground our language, and our thoughts.

Take the issue of masculinity. When talking to men about men it is easy to slip into caricatures: the emasculated man-of-the-cloth wearing vestments like a dress, or the macho preacher yelling for Jesus. It can only be approached through a theology of the body.

Us men must learn to be effective members of the church, the “Bride of Christ.” There is an unashamedly feminine form of intimacy in that notion; we rightly pray, as men, something like “bear fruit in us and with us and through us.” Our sisters, therefore, have much to teach us. The female form of intimacy allows someone to be inside and to leave something there. Men are uncomfortable with that, but need to learn what it means to embrace vulnerability with dignity, honour, and grace-filled empowerment. Without it we struggle to entrust ourselves fully to God, and we certainly cannot nurture and lead his people. For West, drawing on the example of Mary, “every woman’s body is a sign of heaven on earth” (page 25), and that, exactly, is the eschatological nature of the church.

Male bodies have their fragility on the outside, and in our corruption we cover and defend, often by domination. The spousal analogy points to a redemption of this. Christ “gave himself” for his bride, the church. For West, therefore, “the theology of a man’s body can be described as a call to enter the gates of heaven, to surrender himself there, to lay down his life there by pouring himself out utterly” (page 25). No wonder Augustine referred to the “marriage bed of the cross” (page 26). I’ve had enough internal dialogues with myself, and real conversations with other men, to know how dearly we need a cruciform shape to our sexual discipleship.

Clearly, some conceptions of gender, singleness, and marriage are examined by the spousal analogy. It is why these are not second-order issues that are just going to go away. What West does really well is demonstrate how the orthodox or traditional view is not founded on prohibition or repression, but on worship and gospel proclamation. Clearly there is honour in the marriage union of husband and wife; it expresses a divine eros, and it can bear, quite literally, the fruit of new life. But it’s the divine eros that comes first; and none are excluded from it.

…marriage does not express definitively the the deepest meaning of sexuality. It merely provides a concrete expression of that meaning within history… At the end of history, the “historical” expression of sexuality will make way for an entirely new expression of our call to life-giving communion.

(Page 100)

For West celibacy is not a repression of sexuality, but a “fully human – and, yes, fully sexual – vocation” (page 36). All of us – including those of us who are married and sexually active – need to take heed. Our physical yearning is grounded in a more profound yearning that we all hold; to be united in Christ and to see his kingdom birthed in all its fullness. The older I get, the more I realise how that eternal desire is deeper and more profound than that found on the marriage bed. In fact the health of the marriage bed will usually reflect and reveal what is being grasped at the deeper divine levels.

What we yearn for, whether married or single, is a participation in the “spousal meaning” of our body. “Spousal love… is the love of total self-donation” (page 56), and the spousal meaning “is the body’s ‘power to express love: precisely that love in which the human person becomes a gift and – through this gift – fulfills the very meaning… of being and existence.'” Marriage looks back to the foundations of the spousal meaning, celibacy looks ahead to its deepest eternal fulfilment. Neither is ethereal. Undergirding both is an eschatologically pure eros desire for eternal communion.

Christ is the ultimate end of our search for intimacy. For those who are single; a sexual partner will not answer your deepest longings. For those who are married; your spouse and your sexual activity will not do it either. I echo West when he offers “great reverence” for the “cry of the heart for a spouse” of the person who is single and doesn’t want to be. Eros is the “cry of our hearts for the infinite… Whether we are single, married, or consecrated celibates, setting our sights on that eternal union is the only hope that can safely see us through the inevitable sorrows and trials of this life” (page 115). We all long for Christ.

We worship whatever we think will satisfy our deepest desires. Eros yearns for the infinite, crying out to be filled with all the fullness of God” (Ephesians 3:19). In the divine plan, sexual love is meant to point us to the infinite and opens us up to it. But when we fail to see our sexuality as a sign that leads beyond itself to the mystery of God, eros gets “stuck” on the body itself, and we come to expect small “b” beauty to do what only capital “B” beauty is capable of: fulfilling our deepest longings.

(Page 62)

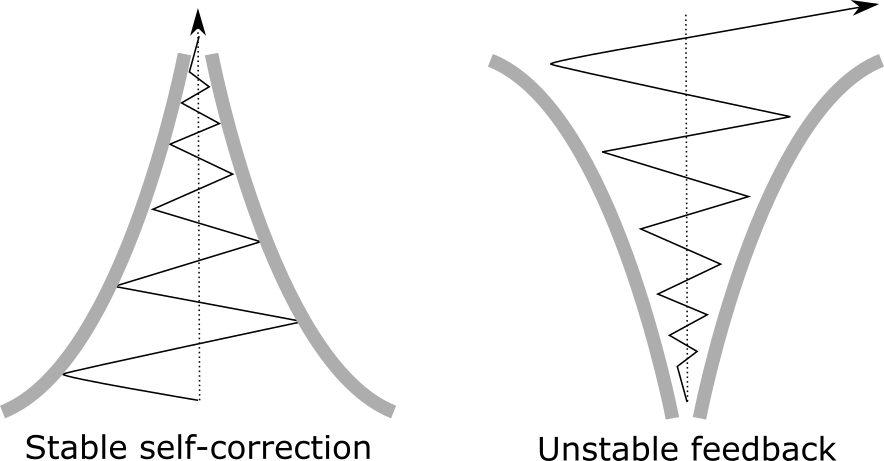

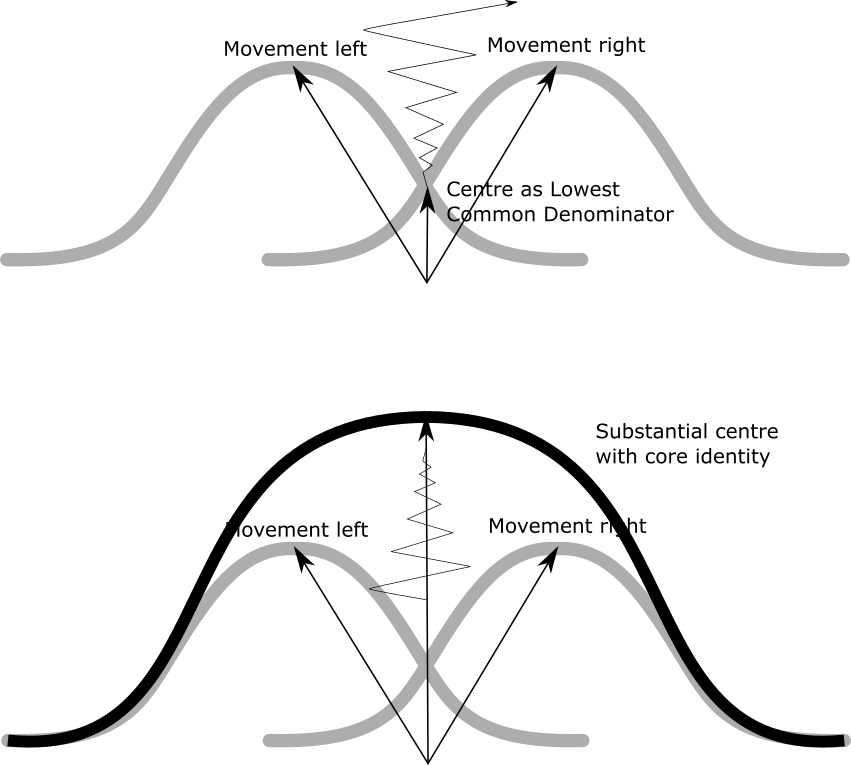

Here, at these deepest longings, the individual and the ecclesiastical intertwine. When the church tears itself apart, it reveals what it worships. At the moment much of the church is tearing itself apart over sexuality. Our eros, our worship, is stuck, and we “don’t really believe God wants to satisfy our desires” (page 73). While we desire something other than Christ – the lusts of our consumerism, traditionalism, activism, nationalism, and even some hedonism – we are simply not a real embodiment of the gospel, not really a church.

But in all things – both personal and ecclesiastical – there is hope. There is the blood of Christ poured out for us on the cross. There is new wine to receive – quite literally in Communion. There is the Spirit of God, holding us, filling us, giving voice to groans, and making all whole, new, and fruitful. God desires us. How can that not awaken and delight our heart?

If Christians themselves don’t believe in the power of redemption to transform eros, what do we have to offer a sexually indulgent world other than rules and repression? If the contest is between the starvation diet and the fast food, the fast food wins hands down. But if redemption can truly redirect our desires toward a divine banquet that infinitely satisfies our hunger, the banquet wins hands down.

(Page 86)

I came to this book expecting some treatise that may inform a church controversy. I have left with some of my cynicism eroded. I have left having brushed against a beautiful thought such that “I was filled with a painful longing, a kind of nostalgia that grabbed me in the chest and became a prayer.” I have found myself praying: “I have been afraid that living from that ‘fire’ inside me would only cause me pain or lead me astray. Awaken a holy and noble eros in me, Lord. Give me the courage to feel it and help me to experience it as my desire for your Fire” (page 109).

Amen.