Review: Reinventing Organizations – An Illustrated Invitation to Join the Conversation on Next-Stage Organizations

What a fascinating book. This is about more than management techniques, it’s a distinct vision of how people might organise, relate, and flourish.

What a fascinating book. This is about more than management techniques, it’s a distinct vision of how people might organise, relate, and flourish.

Reinventing Organizations is doing the popular rounds. I’m going to approach it, learn from it, and critique it from the point of view of church leadership. The author is Frederic Laloux, about whom I know little. It is wonderfully, helpfully (although somewhat, um, caucasianally) illustrated by Etienne Appert. This is not some tome. It’s like a printed powerpoint presentation, and reading it feels like attending a seminar.

Laloux’ framework builds upon an evolutionary understanding of human organisation. He imagines human society having grown through “sudden leaps” (page 18) from “red (impulsive)” communities characterised by gang-like dominance (page 21), through “amber (conformist)” army-like shaping of the world (page 22), through “orange (achievement)” machine-like enterprises (page 26), and “green (pluralistic)” family-like cultures. He imagines, and this is the book’s raison d’être, a “teal (evolutionary) worldview” (page 38) which is shaped by “individual and collective unfolding… taming the ego… inner rightness as compass… yearning for wholeness” (pages 38-39). This is what he examines, explores, and seeks to apply in the real world.

There’s a lot that is good in his vision, and we’ll get to that, but there are two fundamental disagreements with which I must clear the air first.

Firstly, I disagree with the worldview in which he explores these worldviews (his meta-worldview?). It is typical human progressivism: We were once ancient and primitive, and we have slowly grown more enlightened over the years, passing through the different colours of the sociological rainbow until we find ourselves at the brink of the next leap forward. This is not peripheral to his outlook; his vision has a religious fervour. His language is almost eschatological: “This might sound surprising, but I think there is reason to be deeply hopeful… the pain we feel is the pain of something old that is dying… while something new is waiting to be born”! (pages 16-17).

Such language might be novel in the business world, but it’s entirely familiar to the world of faith and spirituality. This world, however, offers the necessary pushback: A linearly progressive story in which we go step by step into either utopia or the apocalypse is rarely a helpful picture. The best eschatology is an insight into the here and now. The different colours and types that Laloux puts forward are useful depictions, but they are less helpful when locked into some sequence of progression. It is more real to think of them as different facets of what human life is like now, and what it has always been. If only he would talk about organisations operating in certain ways rather than at certain evolutionary stages, his work would be much more accessible.

The fact is, we have always had the dominant reds, and the conformist ambers, and the organised oranges, and the organic-but-not-quite greens, and yes, the wholeness-flowing teals. For sure, they have not always been in balance, but they all have their place, and they all have their ongoing, present value. e.g. red organisations can be excellent in a crisis, or where order needs to be brought in the midst of chaos. These worldviews have always been there. To ignore that is to embrace a sort of generational bigotry which refuses to learn from our ancestors who were somehow unable to “hold more complex perspectives” (page 33) than our much more virtuous generation.

Secondly, and relatedly, his teal worldview is nothing new. It might be that it isn’t particularly apparent in the contemporary Western world, and so it is a good corrective. But he isn’t broaching untapped waters here. At best, he is re-discovering something long forgotten.

Perhaps he can’t see it because of a typically prejudicial view of religion that sees the church as being primarily about “rules and traditions” (page 33) and conformity to hierarchy (“oppression” even, page 24). It’s clear he simply doesn’t get religion, especially of the organised Western sort, which isn’t stuck in amber-conformity but orange-machine! I audibly laughed when he assumed that “priests aren’t assigned KPIs, as far as I know” (page 27). He really doesn’t know!

It’s a shame. This prejudice makes this an awkward book to use in a Christian context. Moreover, it overlooks the deep riches there are in faith traditions, including Christian spirituality, that actually supports his teal worldview.

For instance, the language and concept of vocation or calling is ever-present in his teal world. Similarly, the sense of belonging and organic flourishing resonates with Biblical imagery of being members of a body, in which we not only exercise our gifts, but we are a gift of grace to the larger whole. Organic organisations have been part of missiological thinking for some time now; the lifeshapes framework of a couple of decades ago may not always be practiced as it is preached, but it looks to biology in the heptagon and speaks of “low control, high accountability.” Laloux speaks of being a “sensor”, the charismatic and contemplative world speaks of discernment and intuitive insight. He speaks of the teal “yearning for wholeness” (page 39) and I reflect on the language of “groaning” for fulfilment in not only Paul (Romans 8), but the laments of the Old Testament. He speaks of the need for “reflective spaces” and I look to the vast wealth of liturgical rhythms and spiritual disciplines. None of these are on his radar, and that’s a shame.

So Laloux’ wisdom, like most living wisdom, has an unacknowledged companionship and heritage. But in the end that’s not necessarily a problem; there’s still good here.

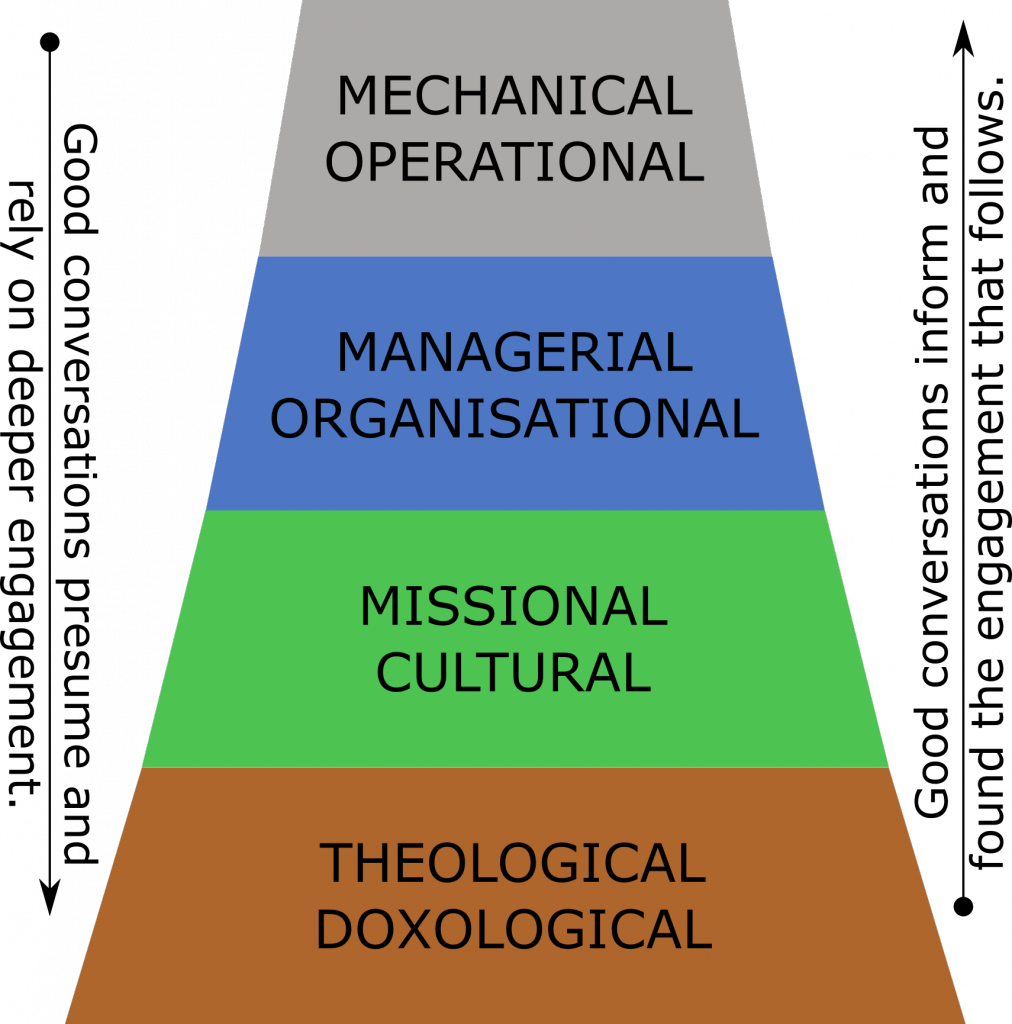

There’s a refreshing honesty in his analysis. I found his exploration of the interplay between the green-pluralist and orange-machine to be very applicable to church leadership. These two worldviews are the predominant ones in the West, and they often collide. Many churches, and most church hierarchies, are unashamedly orange, and they should be ever mindful of orange’s shadow side (page 29). Many who have fallen out of the religious industry now lean towards green. Here we are “aware of Orange’s shadows: the materialistic obsession, the social inequality, the loss of community.” Greens “strive to belong, to foster close and harmonious bonds with everyone… they insist that all people are fundamentally of equal worth, that every voice be heard.” Orange–green typifies, sociologically speaking, the evangelical–liberal divide.

For many, being green seems to be the answer. The reality, however, reflects Laloux’ insight into the “contradictions” of green-pluralist organisations (page 32). It’s certainly something I’ve observed:

In many smaller organisations, in particular in nonprofits or social ventures [churches?], the emphasis lies with consensus seeking. More often than not it leads to organizational paralysis. To get things moving again, unsavory power games break out in the shadows. (Page 32)

I’ve seen such paralysis. I’ve been knocked about by these shadowy power games. The games are often in the shadows of church dynamics; power is often pursued with a degree of self-delusion that denies that power and ego is present at all. It’s a complex dynamic to navigate and Laloux does us all a service by acknowledging it.

There is much that is virtuous about the teal (“evolutionary”) worldview. The interplay of teal’s central characteristic of “self-management”, “wholeness”, and “purpose” (page 55) is an exciting and dynamic way of exploring organisations such as churches. It leads to some aspirations: e.g. to embody a culture in which “we are called to discover and journey towards our true self, to unfold our unique potential, to unlock our birthright gifts” (page 38). I only need to look at my teacher, nursing, and clergy friends, and others who have pursued a vocational path, to see such a yearning.

I resonated with his understanding that the “one critical variable” to the success of organic teal systems is “psychological ownership people feel for their organization” (page 140). It applies to the ecclesiastical world. In the end, a church’s health does not usually come down to capacity, resources, or opportunity; it comes down to motivation. What do we care about? Have we actually bought into the love of God and the Great Commission of Jesus? What’s the difference between our espoused theology, and our actual lived-out beliefs?

I loved his image of the “bowl of spaghetti” (page 139), as a metaphor for the task of unravelling a complex system with simple, sensorial movements. In the church world we speak of “the long walk of obedience” with steps of both discernment and faith. It is similar; each step is gentle tug on a strand of spaghetti, to see what is next on the path.

Above all, I was encouraged to find that as questions arose in my mind, they would almost always be answered.

For instance, he speaks of leaderless self-managed teams, with little if any hierarchy. I could admire the picture, but couldn’t conceive of it working unless there was firstly a dynamic leader who could create the culture and hold the space in which the organic could emerge. His main example of the nursing company Buurtzorg and its leader, Jos de Blok, reinforced what appeared to be a contradiction. How can self-management rely on a dynamic leader?

Laloux recognises the dilemma, and engages with it. He doesn’t eschew the concept of power, as if it doesn’t exist – “the goal is not to give everyone the exact same power… it is to make everyone powerful” (page 123). He recognises the necessity of visionary, culture-setting leaders, such as Jos de Blok. Sometimes “a committed and powerful CEO is needed” (page 144) to be a “public face” and a chief sensor (page 148).

It has similarities with the dynamic of being a vicar! In church traditions we speak of the “apostolic” gifting, which is interestingly connected to, and often at odds with, the “episcopal” function; perhaps that is an orange (episcopal) – teal (apostolic) creative tension! The apostolic covers, and articulates the common purpose around which others are organically coalescing. It is a joy when a church operates in this mode, and doesn’t need micro-managing; “the organization’s purpose provides enough alignment.” (page 125). It’s why we harp on about purpose, mission, and gospel… or at least we should.

This leadership dynamic is especially applicable within the pioneering and church planting worlds. In some circles we speak of pioneer “dissenting pathfinders” who push on into the unknown with gospel purpose; and we have also learned of the need for an “authority dissenter” who covers them and “holds the space” (crf. page 149) in which they can thrive.

Nevertheless, the self-contradictions of the teal vision cannot be fully resolved. For instance, teal is organic and flourishing with self-management, yet in the pragmatics “control is useful and necessary” (page 145). Laloux is honest about most of these tensions, but doesn’t fully resolve them.

I am left, therefore with some unease, and it comes back to the philosophical foundations. Laloux’ vision is effectively a progressive utopianism, and that is rarely, if ever, grounded in the real world.

For instance, it is a virtue for “inner rightness” to be our compass (Page 39); this is the stuff of vocation! But if Laloux had looked into centuries’ worth of engagement on human issues, including the monastic traditions, he would have learned how vocation falls when it becomes self-fulfillment alone. Jesus demonstrates this with his spirit and attitude of kenosis, or self-giving/self-emptying (see Philippians 2:1-11). Ironically, without that kenotic aspect, Laloux’ “inner rightness” is inherently egocentric, tuned in orbit to an individual reality, and not to a grounded, shared, common sense of what is right and wrong. His epistemology is on show here, and it’s basic individualism.

Similarly, consider how “taming the ego” is crucial to Laloux’ vision. It’s an excellent aspiration, to realise “how our ego’s fears, ambitions, and desires have been secretly running our lives” (page 38). Again, if he had looked to the richness of how the traditions have dealt with ego over the years, he may not have missed the balancing perspective. They speak of sin, corruption, depravity, and shame, and the need for communities to both allow for it and protect from it. The teal vision is appealing, but it is only effective, and safe, when there is sinlessness. This is never the case; Laloux’ eschatology is overly-realised!

Laloux speaks often of trust. Trust is valuable. Trust is precious. And it is these things because it is rare commodity within the tensions of the real world. It is right for trust to be withdrawn, because sin abides. Sometimes, walls of protection are what is needed for life to flourish. A worldview that relies so heavily on trust runs the danger of coercing it, and therefore, of doing injury. I did a straw-poll of some friends about their emotional reaction to the phrase “This is a safe space”: the offered responses indicated elevated fear and insecurity. The assertion of “safe space” into a system coerces trust; “If you don’t trust us, you can’t belong.” I can’t shake my sense that the teal vision rests on this subtle manipulation.

This mishandling of the human condition obscures the danger in the teal worldview. For sure, I can see teal dynamics bringing life (there is wisdom in this book!) But I can also see teal structures being a place where the bullies can win, the power-games can be played, dissenting voices can be silenced, and the popular majority can rule over the lost and forgotten. Perhaps, at their best, these structures can be “natural hierarchies” (page 77), but nature can be harsh! We can imagine, with Laloux, the joy of people “showing up in loving and caring ways?” (page 93), but what happens when they don’t?

Similarly, I get that its a virtue to bring your “whole self” to work (page 82), but is it really? My whole self has corruptions as well as goodness. Is that allowed? My whole self has shames and injuries. Should I take those out from “behind my professional mask”, or from behind whatever persona might actually make work a safe place for me and others? There is a subtle demand for exposure in the teal framework, and this is not entirely healthy.

What I do know, from observation and experience, is that the more you lead with the whole of yourself on display, the more you have to count the cost of the inevitable injuries. Every room has it’s shibboleths. Teal isn’t a worldview in which masks can be dropped; it’s a different mode in which different masks must be learned, enforced by tingsha bells.

Vulnerability is inspiring and powerful (let’s hear it for Brene Brown). By definition, however, it is a choice to be self-givingly “unsafe”. There is goodness in it; Jesus himself shows that it is a path through pain to life. We may aspire to this form of open resilience in ourselves, hope for it in our leaders, and nurture others towards it as well. But vulnerabilty cannot be demanded without causing injury. We do not cast our pearls before swine; there’s a reason we offer our deepest parts to the Lord alone, or in close, intimate relationships.

Teal has it’s virtues and I have learned much from this book. But just like all the other colours, I do not think it is entirely safe. “Practices are lifeless without the underlying worldview”, Laloux rightly records towards the end (page 131). And here’s the crux of it. There is some wisdom in this book. Some good things to ponder, insights that can offer a corrective. But in the end, I cannot base my life, my leadership, my wholeness, my organisation upon his utopianism. As a church, we have our founding worldview, and we begin with Jesus.