Sin

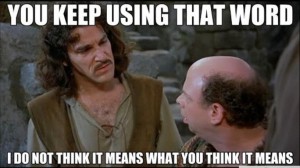

Two conversations have had me thinking about sin. Or to be more specific, what happens when we use the word “sin.” What actually gets communicated?

The first conversation was a wonderfully deep intelligent conversation in which I and my interlocutor were seeking mutual understanding on a whole swathe of issues. The relevant part involved a hypothetical where I was asked, “How would I speak to someone in situation X?” My response was, “I suppose I’d probably begin by saying ‘Well, we are all sinners.'” The response to this was some genuine, well-hearted, dismay… “Oh yes, that’s where you lot start from…”

What I intended in my response to the hypothetical was an attitude that eschewed holier-than-thou-ness or condemnation. For my part, “We are all sinners” is the great leveller. It says “I am not better than you” and “I cannot condemn you, for if I did I would also condemn myself.”

It’s not like this was beyond the capacity of my conversationalist to understand. The conversation delved into areas of a relevant common human experience: how we all wrestle with both the broken parts and healthy parts of our lives; how even the most well-intentioned relationships cannot hold selfishness at bay 100% of the time; how in our finitude (if nothing else) we each end up committing and suffering harm. This is simple reality that we both recognised.

But somehow the word “sin” or “sinner” didn’t connote any of that…

The second conversation was with someone who has a Christian faith but lives in a non-Christian context. She shared the evisceral reaction to the word, because that reaction has been part of her world: “‘Sin’ doesn’t work, it get’s turned off and tuned out.”

But, it was noted, there are words that do work. “Brokenness” is one of them. Everyone of us can acknowledge that we are broken. “Darkness” is another, recognising the fact that sometimes we just want what we want, we do what we know is harmful and wrong. Even the phrase “rebellion against the things of life” gets more traction.

The conclusion of course, is not a new thought: The word “sin” doesn’t work as a word anymore. It doesn’t do what words should do – encapsulate and communicate meaning. It’s Christian jargon. But it’s worse than that, from this perspective it signifies our self-justifying delusion, “sin” is our construct to justify our own existence and exercise power over others.

The conclusion of course, is not a new thought: The word “sin” doesn’t work as a word anymore. It doesn’t do what words should do – encapsulate and communicate meaning. It’s Christian jargon. But it’s worse than that, from this perspective it signifies our self-justifying delusion, “sin” is our construct to justify our own existence and exercise power over others.

This is not hard to understand, but it something we need to emotionally appropriate. An exercise for (the much caricatured) Christian conservatives might be something like this: You know how we feel when we get called bigots and hatemongers? We not only find it derogatory and disconnected from the reality of who we are, and hypocritically hateful, we also consider it as polemical self-justification: if they can maintain the rage against the bigoted Christians, they can get more votes. You know how that makes us feel? On the flip-side, for them, that’s what happens when we use the word “sin.”

So what do we do about it? Do we stop using the word? Perhaps. After all, our job is to communicate, and it’s not like the word is sacrosanct. Are we not preachers, homileticians? Our job is to connect the worlds and get the meaning across. Just as I don’t quickly use jargon words like “eschatology” or “propitiation” (although I do try to communicate the substance of them) perhaps we should also be careful in how we describe our harmatology.

It’s not like there isn’t precedent. In New Testament Greek “sin” is ἁμαρτία (harmatia) which connotes “missing the mark” or “wandering from the path” of God’s good ways; it speaks to a more fundamental wrongward inclination. It is also παράπτωμα (paraptoma) which has more of the connotation of “trespass”, “wrongdoing” or “lapse”; it speaks more to specific actions that are wrong or done wrongly.

I think we are being lazy. Rather than communicating our intent, we use an ineffective jargon word, in which we expect even our interested listeners to do some semantical gymnastics in order to keep up with us. But even more worryingly, we end up lazy with our own thoughts, using a catch-all word where precision is necessary not only for mutual understanding, but for genuine expression that is also loving and caring.

Therefore, and to conclude, let us take a look at the pallid rainbow of the darkside of human existence. To be honest, even in my current use I wouldn’t apply the word “sin” in all these instances. But it seems, that when we use the word it may be taken that way. It’s worth a consideration; after all, if we use “sin” intending to communicate something akin to “wrongdoing” or “mistake” and it is heard as “evil”, we can do immeasurable harm.

EVIL: “Sin” pertains to those things that are utterly antithetical to the things of life. “Sin” reigned through the workings of Pol Pot and Hitler. “Sin” is manifest at it’s highest in serial killers and torturers. “Sin” is diabolical, demonic, irredeemably hell-bound.

CRUEL INTENTIONS: “Sin” pertains to those who delight in pain. “Sin” pertains to sadistic abusers who are fully aware of what they are doing. This “sin” is not so much a desire to win but a desire to defeat others, no matter the cost. If it is not quite an evil lust for power, it is certainly a lust for control.

DELIBERATE REBELLION/HARD HEARTEDNESS: “Sin” pertains to those who manifest selfishness at its utmost. “Sin” will cast others aside in order to get what is wanted. This “sin” is machiavellian in the extreme. Others are means to an end. Responsibilities cast aside, abandonment, and rejection. All this is “sin.”

SENSUAL PASSIONS: “Sin” pertains to the idolatry of human passion. This is the domain of the “seven deadlies” – from raging anger, to rampant lustfulness, the flesh is king. Persons are reduced to animals, fresh meat, gold mines, for the satiation of appetite.

BONDAGE: “Sin” pertains to addictive behaviours. False comforts that are destructive, but provide temporary physical or emotional relief. Often in response to harms of the past, a destructive cycle becomes our own, and without consideration we ourselves become harmful.

NEGLIGENCE: “Sin” pertains to carelessness and neglect. Sins of omission which overlook or diminish others. Sins that refuse to see the image of God in the face of others. Racism and xenophobia, at the very least, are “sin” at this level.

MISTAKES: We stuff up. We hurt people. We harm them. And whether it is intended or not, such mistakes are our responsibility. We have done the wrong thing, and that is “sin.”

BROKENNESS: We are wounded, we are hurting. And often this means we believe wrongly about ourselves. We think we are evil, when evil has been done to us. We root our very person into shames that have been wrought upon us. At a very gentle level, this thinking about ourselves is wrong – and like all “sin” we must turn away from it.

As a final thought: In writing the above, the usefulness of the word “sin” in covering them all is that there is one answer to all these dark things: Jesus. From the defeat of evil at the top, to the gentle healing of brokenness at the bottom, he is the answer.