Four Levels of Church Conversation

There’s something to observe when Christians get together and talk about themselves in meetings, in groups, or even over coffee. It’s an observation that relates to the question of “what is this meeting for?” and “what are we not talking about?”

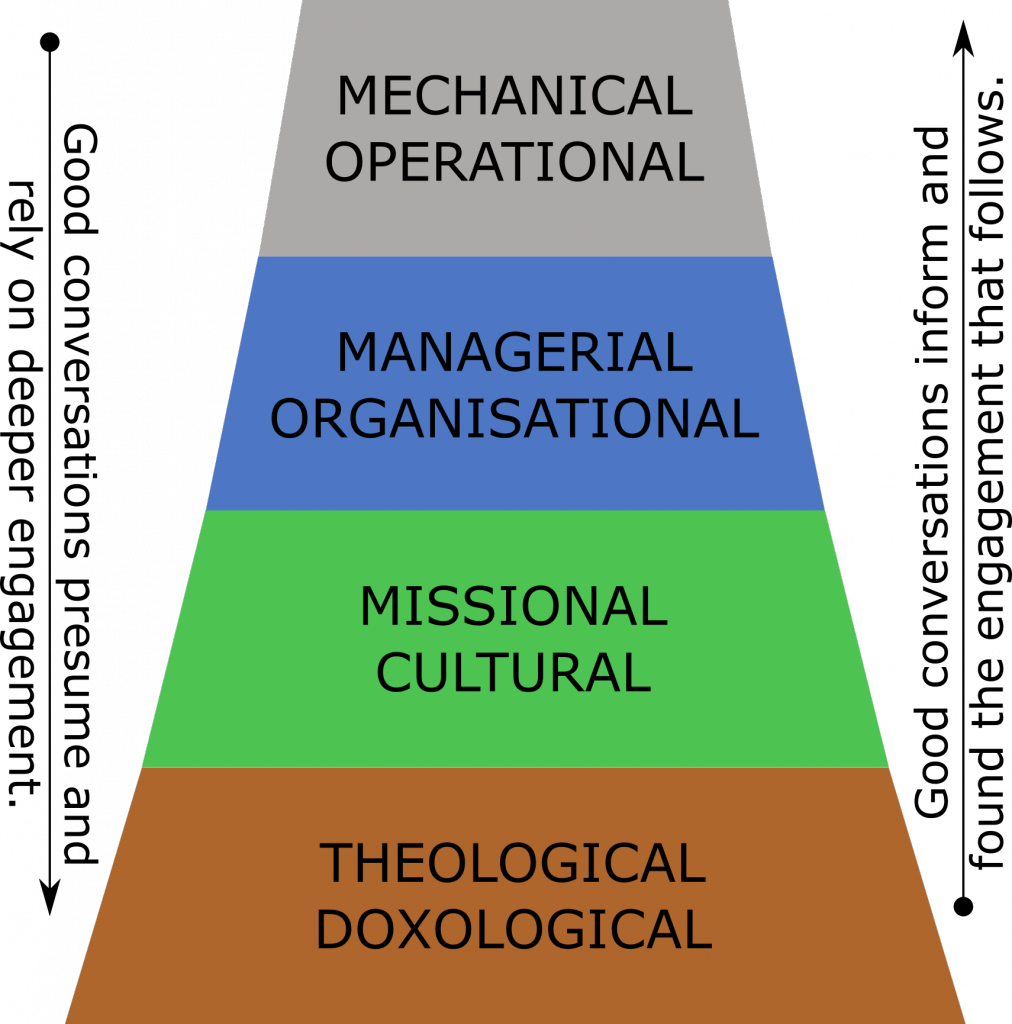

Here is how I’ve come to answer that question: by identifying four levels of conversation. It’s an oversimplifying categorisation, for sure, but hopefully a useful way to discern what page a conversation is on.

The top level of conversation is mechanical and operational. Like coats of paint, it’s this top layer that is on the surface and is often the easiest level to enter into.

It is at this level that we find ourselves talking about operations: planning services, organising rotas, remarking on how good the flowers look, the size of the congregation, the clarity of the sound, and the feel of the sermon. These are all necessary things to discuss and it’s not for no reason that such topics dominate the agenda of many meetings, and make up the bulk of a minister’s emails and phone calls. Things need to happen, programs need to run, and coordination and conversation is required to do that.

Conversations at this level, however, presume and rest upon an understanding about how the church operates. That’s the topic of the next level of conversation:

The second level of conversation is managerial and organisational. At this level, it’s not so much about keeping the church operational but improving those operations.

These are conversations that deal with priorities, financial allocations and budgets, improving efficiencies, and responding to hiccups and crises. A good engagement at this level keeps things running smoothly. Most complaints and criticism are also at this level because they usually relate to how things could supposedly be done better. Boards and oversight committees often spend time talking at this level.

These sorts of conversations inform and found how we talk about the operations of the church (the previous level), and presumes the church’s mission and purpose:

The third level of conversation is missional and cultural.

This is where questions of identity, purpose, and values are considered. It’s a level of conversation that is both reflective and strategic.

It is reflective, in that it involves questions about ourselves: Who are we? Where are we going? What are we for? What’s really important? What are we struggling with? What is good about us that needs to be affirmed? What is wrong that needs to be addressed? Where are we clinging to idols that we should put away? What gifts are we ignoring that we should cling to? What is our culture? Where are our blind stops? What makes us tick?

It is strategic, in that it involves questions about mission and calling: What is God doing in with and around us? Where is he leading us? What is his heart for the people and place in which we find ourselves? What is the culture in which we find ourselves, and how do we bear witness to the gospel in the midst of it? It is in this sort of conversation that vision and purpose are tussled through and articulated.

Conversations at this level can be quite rare. Such engagements are usually motivated by passion or crisis, or both! Where the context is marked by stability, or even stagnancy, these topics are rarely broached; the presumed answers suffice for the sake of management and operation. This is understandable; for conversation at this level to happen well, there needs to be a willingness to embrace the challenge that these sorts of questions generate, and that often requires facing fears and insecurities and daring to dream and be imaginative.

Conversations at this level inform and shape how we talk about the management and organisation of the church (the previous level), and presumes a theological and doxological basis:

The base level of conversation is theological and doxological and deals with spiritual foundations.

These conversations can sometimes feel a bit academic or esoteric. This does not necessarily mean that they are not delightful, dynamic, and life-giving. The main contributor to my own theological formation was coffee with fellow students! I have wrestled with fellow colleagues about things like Neo-Calvinism (when it was a new thing) and New Perspectives (which still is). There might be no clear application for such discussions, but they do shape the foundations upon which all other conversations rest. What do we believe? And why?

Of course, “theological” doesn’t just mean cerebral things. Theology cannot be divorced from doxology. The conversations at this level are also intensely spiritual. I have had delightful conversations with deeply contemplative folk who make use of art, symbolism, metaphor, and even silence. Shared spiritual disciplines are located here. It is at this level that our conversations come close to the heart of worship.

Again, these sorts of conversations can be few and far between, even in a church setting. There is often an intense sense of privacy and vulnerability that prevents the dialogue. We often tend to mitigate this by relegating these sorts of topics to a didactic sermon or by speaking in abstractions so that awkward conclusions can be avoided. Yet this sort of engagement is the stuff of life, it is where we discover a common root for our passions, a base level unity that founds a true and open community, irrespective of disagreements at the other levels.

Diagrammatically, it looks like this:

It is a simplification, but it does help as we ponder how we ourselves engage in dialogue about the church.

I suspect that every one of us is more comfortable engaging at one level more than another. And sometimes we try and do things at the wrong place. This is the situation where a conversation about hymn selection is not about the operation of the music ministry, but actually a commentary with regards to priorities, purpose, and base values; the issue is rarely the issue! This can help discern where the conversation needs to go.

But it also reminds us of the conversations that we need to have but sometimes never get around to. The management meeting that spends all its time on minutiae and forgets the important things is a well-known experience. The old analogy of the church that forgets that it is a lifeboat station is a failure to have the deeper conversations at the right time and in the right way.

The thoughts, and hopefully the conversations, continue.