Review: The Grace Outpouring

This book comes from Welsh retreat centre Ffald-y-brenin, but that place, and author, Roy Godwin, are not the point. Here’s something from the book, in Roy’s words, that gets to the heart of the real issue for me:

This book comes from Welsh retreat centre Ffald-y-brenin, but that place, and author, Roy Godwin, are not the point. Here’s something from the book, in Roy’s words, that gets to the heart of the real issue for me:

A number of years ago I felt a cry rising up in my inmost being – “There has to be more than this.” As I remembered my dreams of what living as a child of God would be like, there was that cry again. There has to be more than this. I was stirred by memories of great days in the past when God had seemed so close, but that’s where they were – in the past. Oh God, there must be more than this.

Looking at church initiated the same cry. There is so much good, so many signs of blessing in many local churches and fellowships, but looking more broadly at the national scene raised the question “Is this really all that the Father has in mind for the bride of his Son?” (pp180-181, emphasis mine)

This book taps into a divine sense of dissatisfaction. I don’t think it’s unique to our time and place; I see it echoed in the lives of many Christian saints, both historical and contemporary. It’s a dissatisfaction that is eschatological in nature (Romans 8:22-23) and speaks to the sense that until our Lord returns there is still more gospel work to be done. The Great Commission to go and make disciples remains in place.

In our experience, Gill and I have encountered people and places that are entirely satisfied with the status quo. Any dissatisfaction is a commiseration about the good old days rather than a cry for more. This is a dry place to be.

But for those who are dissatisfied the next question, of course is “What do we do with it?” How do we act on it? We have seen a variety of responses. All are well-intentioned, but some are problematic. The essence of the problem is this tension: in order to get good things done we take control, but nothing will satisfy if we do it in with and for ourselves.

We’ve seen it in mission agencies where the dissatisfaction leads to impatience, lack of care, vision without process, and ineffectiveness. We’ve seen it in congregations where that dissatisfaction turns into yet another program which is an attempt to scratch the itch so as to return to comfort, or prove worth, or not seem lazy, or simply “do what good churches should do.” We’ve both been driven in these sort of ways. It’s a frustrating place to be.

There’s a difficult tension at the heart of an effective ecclesial spirituality – to be dissatisfied, stirred, motivated, urgent, expectant; and let God be God and build through us, not in spite of us. It isn’t quietist or passive – things get still get done. But it is built upon a foundation of prayer, and being attentive to God’s Word and the providential promptings of His Spirit.

The Grace Outpouring hits us at the sweet spot of that tension. It promotes the dissatisfaction, it stirs us to action, and so it pivots us to turn to prayer, expectant prayer.

Roy, and co-writer Dave Roberts, do this simply by sharing the story of Ffald-y-brenin. Yes there’s some explanation and some reasonable theologising and all the other things that get a point across, but in the end they just want to share what God has been doing. Dave writes in his foreword:

…as people who model our lives on a storyteller, we’re best advised to do as he did and tell the stories of what God has done. So we invite you to join us as this story unfolds. We’ll draw out principles and go to the root sources in Scripture, but we hope that what you read will help paint pictures on the canvas of your imagination that will allow you to be provoked by the Holy Spirit to prayer, compassion, and a mind-set that desires to bless others. (p14)

I can’t do justice to the story here, but it truly does creatively provoke.

Along the way we do encounter some of the definitive Ffald-y-brenin experiences. To consider two of them:

Blessing: In the story Roy shares how his was initially an “accidental” tradition – to speak a blessing over all those who come to Ffald-y-brenin. To be a recipient of it is profound. Gill and I experienced this first-hand when we travelled to the centre a few weeks ago; tired and exhausted from a long day of travel and some of the complexities and perplexities of life we were shown to our room, and then to the chapel, where life-giving utterly-relevant personal words were spoken over us in Christ’s name. I hadn’t read the book before we went; I wasn’t expecting it! It set us on course for a deep and meaningful time with God.

We don’t always know what to do with “blessing.” In some popular thinking blessings are almost like magic, talismanic words; this is usually unhelpful, and inhibits access to the gospel. For others, “blessing” is simply an indistinct form of prayer. Roy is right when he distinguishes blessing from intercession; as he points out to offer a blessing in Christ’s name is a bold, daring, and necessarily humble action of someone who takes seriously the priesthood of believers and the ambassadorial nature of the Christian vocation, and seeks to exercise it with generous care. It may not be a rigorous theological treatise, but I admire the thoughtfulness:

We’re invoking the very character of God himself into the lives of those we pray for. They’re getting a foretaste of being adopted into God’s family. We’re opening a door for them to glimpse something of the kingdom of God. God is saying, “I’m going to bless you with everything I’ve blessed my children with.” (p36)

There is something right and properly kerygmatic in turning our holy dissatisfaction into words of blessing, to articulate, to proclaim the creative life-giving heart of our Lord and Saviour specifically, personally, and locally.

House of Prayer / New Monasticism: In the story a Welsh Christian retreat centre becomes a “House of Prayer” and Roy expands and expounds this by referring not only to the daily rhythm of prayer that is exercised at the centre, but also to the outward-looking movements that are as near as hospitality and acts of service, as far as intercessions for nations and global movements, and as deep as the revivals of the Celtic and modern Welsh church. I reflected earlier about how this compares to our English context.

Gill and I have brought the daily rhythm of prayer into our home and are seeking to share it in some form with our church. The daily reminder, using words of Scripture to cause us to bring to mind the characteristics and promises of a faithful God, has blessed us. We have somewhere to give that holy dissatisfaction a proper beginning, a turning to God, a daily repentance, a discipline of intercession and expectation.

Towards the end of the book Roy connects the dots with the amorphous movement that is becoming known as the “New Monasticism.” It has deep and ancient roots of course. In current manifestations it invokes simplicity, purity and accountability in ways that express the holy dissatisfaction in profoundly counter-cultural ways. They are ways that tear down middle class idols.

…Local House of Prayer involves sacrifice, just as it did in the Old Testament times. Among our offerings we will bring our worship (not necessarily singing) and the spirit of the community around us. We will need to set aside our rights, judgmental attitudes, pride, and self-righteousness. We will lay down our bodies and our patterns of thinking as living sacrifices for God’s glory and his purposes. (pp167-168)

After returning from our recent visit to Ffald-y-brenin, Gill and I have been pondering these things. What I have read of here, and what we have encountered has informed our dissatisfaction. It has renewed our passion for God’s Word and Spirit, and a determination to rely on him, rather than to burn-out in our own strength.

After returning from our recent visit to Ffald-y-brenin, Gill and I have been pondering these things. What I have read of here, and what we have encountered has informed our dissatisfaction. It has renewed our passion for God’s Word and Spirit, and a determination to rely on him, rather than to burn-out in our own strength.

These things have been stimulated by our visit, and we will return. But it’s not about the place, or the person. It’s about doing the hard yards of following God. Of seeking him in the dissatisfaction, not collapsing it, not running away from it, but facing the pain and patience of it, and actively pursuing his way; so that at the end of it all he is glorified as God’s people are blessed to be a blessing.

Like churches themselves, there’s a tendency for those of us in pastoral ministry (ordained and lay) to become

Like churches themselves, there’s a tendency for those of us in pastoral ministry (ordained and lay) to become  I have an ongoing interest in the interaction between first-century rabbinical Judaism and Christianity. On each exploration I find increased depth and colour to my reading of the New Testament. I picked up Boyarin’s book The Jewish Gospels on something of a whim and for the title alone.

I have an ongoing interest in the interaction between first-century rabbinical Judaism and Christianity. On each exploration I find increased depth and colour to my reading of the New Testament. I picked up Boyarin’s book The Jewish Gospels on something of a whim and for the title alone. If you want a decent overview of contemporary men’s ministry, this will give it to you.

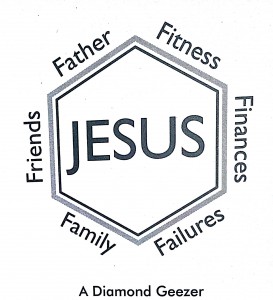

If you want a decent overview of contemporary men’s ministry, this will give it to you. But the word diamond is quite deliberate. Delaney takes a six-faceted look at being a diamond geezer. He deals with six “f-words” which are basically an exhaustive list of the things that are found when working with men: fitness, finances, failures, family, friends and father. That is, blokes need to deal with their health issues, their wealth issues, their daddy issues, their loneliness, their relational brokenness, and their insecurities. Tying it all up is the call to live life for Jesus.

But the word diamond is quite deliberate. Delaney takes a six-faceted look at being a diamond geezer. He deals with six “f-words” which are basically an exhaustive list of the things that are found when working with men: fitness, finances, failures, family, friends and father. That is, blokes need to deal with their health issues, their wealth issues, their daddy issues, their loneliness, their relational brokenness, and their insecurities. Tying it all up is the call to live life for Jesus. Gill and I have read many books during our life in ministry. Many are helpful, a few are frustrating, and quite a lot are downright disappointing. But some are set apart by being theologically robust and wonderfully relevant and accessible. These are the books that we end up buying multiple copies of and giving away.

Gill and I have read many books during our life in ministry. Many are helpful, a few are frustrating, and quite a lot are downright disappointing. But some are set apart by being theologically robust and wonderfully relevant and accessible. These are the books that we end up buying multiple copies of and giving away.