Q&A: What’s your take on spiritual attack, Satan, demons, and all that kind of stuff?

Anonymous asks:

What’s your take on spiritual attack, Satan, demons and all that kind of stuff?

How do you know what’s actually ‘powers and principalities in the heavenly realms’ and us over spiritualising stuff (ie: ‘I lost my keys… IT MUST BE SATAN!!!!!’)

[This is a Q&A question that has been submitted through this blog or asked of me elsewhere and posted with permission. You can submit a question (anonymously if you like) here: http://briggs.id.au/jour/qanda/]

Thank you for an interesting question. I’m going to approach it in two different directions: Firstly, by looking at Ephesians 6, which you are quoting. Secondly, by unpacking some of the popular thinking and experiences of “spiritual attack” and seeing if we can make sense of it.

Thank you for an interesting question. I’m going to approach it in two different directions: Firstly, by looking at Ephesians 6, which you are quoting. Secondly, by unpacking some of the popular thinking and experiences of “spiritual attack” and seeing if we can make sense of it.

So, firstly, POWERS AND PRINCIPALITIES IN THE HEAVENLY PLACES.

You are quoting Ephesians 6:12:

For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms. (NIV)

As with all snap quotes from the Bible, the best way to grasp the meaning is to look at the verse in its context. This verse, for instance, uses a bunch of keywords and phrases that Paul is threading into his letter to the Ephesians.

One of these threads is the phrase “heavenly realms” which, here in 6:12, is the location of “spiritual forces of evil.” However, at the beginning of the letter, in his opening lines (Ephesians 1:3), it is also the place of “every spiritual blessing:”

Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who has blessed us in the heavenly realms with every spiritual blessing in Christ. (NIV)

The phrase “every spiritual blessing” ties back into the fundamental hope and mission of God’s people, to embody the covenant promise of God, that Abraham would be blessed, and so bless the whole world. God keeps his word, and fulfils his promise in Jesus. And now the whole world – Jew and Gentile – are drawn together in Christ into that same blessing. This is God’s victory, purpose, and wisdom, and it is also present “in the heavenly realms.” In Ephesians 3:10-11 we read:

His intent was that now, through the church, the manifold wisdom of God should be made known to the rulers and authorities in the heavenly realms, according to his eternal purpose that he accomplished in Christ Jesus our Lord.

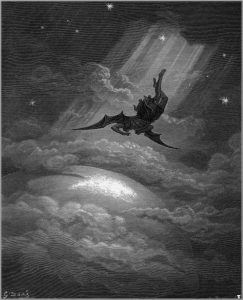

What, then, are the “heavenly realms”? The popular caricature is of clouds and cherubs or something like what is imagined in The Good Place. In this imagining, heaven is “up there”, the real world is “down here” and while there may be the occasional cross-over, with souls coming and going and angels and demons intervening from time to time, they are essentially separate. Perhaps this is close to the imagined scenario of demonic key thievery that you allude to in your question.

It’s the same with the word “spiritual.” We take this word and we often make it mean something like “ethereal” or “out there” or “other.” So “spiritual blessing” becomes something pie in the sky and “spiritual warfare” makes us think of some Greek-legend type battle going on in some distant galactic plane; we participate by making sure our little patch of the here-and-now on earth is backing the right side.

I don’t see any of that in Ephesians.

Rather, for Paul, the idea of “heavenly realms” and spiritual things is fully intertwined and interconnected with real-world experiences, and real-world “powers and principalities.” He uses language that draws on a cosmology in which the earth itself is immersed in the “heavens”, plural.

In this framework, one of the heavens is the very atmosphere we breathe. After all, you can’t see the wind, but you can see what it does; it’s an unseen power, intertwined and interacting with all that exists and all that happens. And so Paul speaks of a spiritual power in Ephesians 2:2 as the “ruler of the kingdom of the air.” He literally means the air. The word “spirit” in the Greek is “pneuma” – meaning “breath” or “wind” – from which we get words like “pneumatic tires.” Your car tyres are filled with the heavens, and your lungs are spiritual pumps. We live, breathe, and are immersed in this spiritual realm.

Paul’s worldview simply extrapolates this. The wind speaks of unseen power, and Paul sees other unseen “powers and principalities” that are, nevertheless, real and present and intertwined with our existence. Think of how we talk about people being affected by “market forces” or having circumstances that change with the “political atmosphere” and you’re starting to get a glimpse of what he’s talking about. We talk about the scourge of “long-term unemployment” or an “epidemic of alcoholism” or an “hypersexual milieu” or “a patriarchal culture” and we have a sense of encountering powerful things that are real but invisible. For Paul these grounded, connected, intertwined-with-reality heavenly realms are a location for God’s activity and intervention.

These “heavenly realms” include “spiritual forces of evil.” I can imagine the winds of the military conflict, or engrained injustice, or the bondage of addictive behaviours, being expressions of demonic activity as well as human sin. That’s Ephesians 6. But I also see God’s assurance to his people: “I have blessed you with every spiritual blessing” in these heavenly realms. God’s intervention in his creation is through his new people, brought together in Jesus. Against the injustice, and cruelty, and diabolical hatred of the image of God in humanity – i.e. against the powers and principalities – God has made his people not to be caged and slaves to fear, but blessed and victorious. We now put on the armour of God, and live and work towards extending that blessing in the power of the Spirit.

So, to return to your question, what’s my take on “spiritual attack”? It is the very essence of growing the Kingdom of God. As we worship, and proclaim, and act in accord with God’s truth and purpose, we impact and overcome the unseen powerful things that are in the air around us. We look to see lives, families, communities, cities, nations moved by the right Spirit. After all, that is what it means to “baptise nations in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” (Matthew 28:18-20); it is to immerse nations in God’s character, under the authority of King Jesus, and “teaching them to obey everything that Jesus commanded us.” Just as Jesus rose from the dead, just as the earth and the heavens will be made new at the end, so this evangelistic good-news bringing mission overcomes these unseen evil powers.

I can imagine some of those unseen powers wanting to undermine that work: lie instead of truth, bondage instead of freedom, cruelty instead of justice, chaos instead of peace. When we encounter those strongholds, or when they encounter us, that’s what I think of as “spiritual attack.” This is where Ephesians takes me.

But secondly, to reflect, just quickly on our PERSONAL EXPERIENCE OF SPIRITUAL ATTACK.

Often this comes into play when we have a negative experience: e.g. We experience loss, bereavement, disappointment, hurt, pain, frustration, sinfulness. Maybe we even lose our car keys (I once couldn’t find my car keys and missed out on an important family occasion, that certainly felt like a loss). We interpret this pain as “spiritual attack” and somehow deflect the pain and attempt to give it some meaning. Sometimes we are grasping at something that’s not there.

Are negative times like these “spiritual attack”? I have a “yes” and “no” answer.

My “yes” comes when I can discern an active aspect of those powers in Paul’s heavenly realms.

I have, for instance, seen good people, doing good things for the kingdom, facing vehement accusation and even hatred. It’s a step beyond mere frustration, it is almost irrational; something in the atmosphere shifts and it is conceivable that something unseen is out to get good people, and tear them down. It makes me want to put some Ephesians 6 armour on.

Similarly, I have seen people battling addictive behaviours and the general malaise of life; I have seen them begin to lift their heads, breathe some freedom, get some vision, only to be broadsided by something and brought back down. It’s as if something has reached up, like the Balrog with Gandalf, and dragged them back into bondage. It makes me want to pick up some of God’s truth, and fight for them.

My “no” comes when I discern other things at work:

We live in a fallen world. Bad things happen to good people. Sometimes, simply, detritus happens, as the saying goes. The focus at these times is to bring it all back to Father God, the source of the evil is neither here nor there.

Sometimes the adversity is a “time of trial.” Was Israel’s wandering in the wilderness “spiritual attack”? Was David’s time in exile “spiritual attack”? Is Job’s story a story of “spiritual attack”? I’m not sure I’d even classify Jesus in the wilderness as “spiritual attack”, despite the actual demonic presence! Rather, these are often times when the devil must beat a hasty retreat! It is in these times that the Lord builds our faith, bolsters our reliance on him, and draws us to himself. If there is any “spiritual attack” on the church, it is not so much in the adversity we face, but in our addiction to comfort and our demand to meet God on our own terms! Be wary of the evil one when things are easy, not when things are hard.

Thanks for the question.