Review: Good Disagreement? Pt. 7 Ecumenical (Dis)agreements

I am continuing with my chapter-by-chapter, essay-by-essay review of Good Disagreement? Previously:

I am continuing with my chapter-by-chapter, essay-by-essay review of Good Disagreement? Previously:

- Part 1: Foreword by Justin Welby

- Part 2: Disagreeing with Grace by Andrew Atherstone and Andrew Goddard

- Part 3: Reconciliation in the New Testament by Ian Paul

- Part 4: Division and Discipline in the New Testament Church by Michael B. Thompson

- Part 5: Pastoral Theology for Perplexing Topics: Paul and Adiaphora by Tom Wright

- Part 6: Good Disagreement and the Reformation by Ashley Null

This chapter is the first in this book to exceed my expectations. The focus is less on the division and more on the possible ways forward. It is not prescriptive, it simply gives a potted history of ecumenical movements, and the descriptions are insightful for the present concerns.

The helpfulness of this chapter shouldn’t be a surprise. I observed earlier that there are many ways in which the Church of England appears to act as a conglomerate of churches already. It’s not absolute of course, there are many things in common particularly at the episcopal level, but it is not a stretch for the dynamics to apply. It is interesting, for instance, that the authors see fit to put constructive “liberal-evangelical” dialogue, such as that between David Edwards and John Stott who are both Anglicans, within the scope of ecumenism (see p115).

Three observations:

1) The most helpful characteristic of ecumenical interactions is that of honesty.

Good ecumenical interactions do not presume full agreement, and dialogue often serves to “bring areas of disagreement into sharper focus in order to clarify the real sticking points.” (p117)

This is good disagreement in the sense that it is actually disagreement. It is honest and does not demand a pretence. A holding together of both unity and truth is the right aspiration, but unity is not constructed of it’s own bricks. Unity’s material comes from discussions on truth:

The result of honest conversations between divided churches may be that different positions are shown to be incompatible and contradictory, and therefore the divisions must remain. This does not make the conversations fruitless but, on the contrary, pinpoints where change is necessary for unity to proceed. (p117)

Of course, avoiding a pretence is easier when it’s different churches talking. But between Anglicans, who share, for instance, a common language of prayer, it’s a lot harder. Some collective honesty about differing semantics would bring us closer to the more constructive dynamic described here.

To this end, confessionalism can be significantly helpful. When done well (a big caveat), it clarifies meaning, it removes pretence, it allows conversation. I was told once of an Australian Bishop of a non-conservative variety who, to the surprise of some, welcomed the Jerusalem Declaration that arose from GAFCON. His response was, without any hint of disparagement, of this kind: “Now we know where you stand and we know where you’re coming from. That is helpful.” Irrespective of whether this anecdote is true or not, that’s the sort of attitude that advances things. Confessionalism risks clarifying the divide (which may be fearful to some), it may even risk the “split” (whatever that means), but without it we have an inhibiting lack of clarity.

If there’s anything I’ve learned from my own experience, if an honest appraisal of difference is not achieved, and if possible separation is not acknowledged, or even embraced, there is likely no room for reconciliation at all.

2) Separation doesn’t preclude all forms of unity.

I was struck by the reference to Francis Schaeffer’s idea of “co-belligerence”, “that churches can go into battle together on specific issues of social concern, without the need for doctrinal agreement.” (p114)

I like the term “co-belligerence” and have seen it in action. In my time in Tasmania I was involved in the response of churches to what became known as the “social tsunami” of 2013 in which a radical socially revisionist state government attempted to impose a whole swathe of divisive legislative changes. It was a most ecumenical experience – I met with everyone from across the entire range of Christian expressions, from Roman Catholics to Quakers, from Pentecostals to Presbyterians. Someone expressed it this way: “I thought we’d be in this corner fighting by ourselves, and then I turned around and there were all these others with us!” We were being co-belligerent. The doctrinal common ground was thin, to say the least, probably limited to the very basics of what the WCC of churches provides (see p24) and yet there was a substantial form of unity.

Similarly, I count as dear friends many who differ from me on points of theology. There are many things about which I think they are incorrect, and, in some circumstances, worthy of being opposed. Yet, despite this, I am convinced of a shared spirituality. We pray to the same God. We trust in the same Christ. There are times when we are separate, and firmly so! Yet we can bless each other, even if we cannot bless each other’s position. (Of course, the flip side is there are people who are correct doctrinally, but not right in spirit, but that’s for another time).

There are many things where Anglicans truly do act as one. Advocacy for refugees is a near and present example. This sort of unity is not necessarily at risk of honesty about differences being embraced and explored.

3) Even minimalist common ground can still quake.

The ambitions of ecumenism are described in this chapter. The “organic unity” of sweeping reunion across the board, particularly in terms of shared modality is one of them (p120). The other form of ambition is “reconciled diversity” (p122) in which certain expressions of unity cohere to a minimalist fundamental common ground, and all other things are held separate.

I am pondering how these apply to the Anglican concerns. Ostensibly the Church of England is an “organic unity”, yet beyond the structural necessities, doesn’t appear to be behaving so. But I am an Anglican from further afield, ordained in the Anglican Church of Australia. There Anglicanism is a federalised arrangement of dioceses in which even General Synod canons can be ignored in each local place. The wider perspective is that of independent national provinces.

It is a clearer perspective of a diversity with minimalist common ground. That ground is, in history, that of the so-called Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral. These are the four (only four!) things that are fundamentally necessary to being Anglican. They arose during colonial times, and have more recently been wrestled with by fresh expressions and church plants working out their ecclesial identity. They are, to quote:

1. the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testament as the rule and ultimate standard of faith.

2. the Nicene Creed as the sufficient statement of the Christian faith

3. the two sacraments ordained by Christ himself: baptism and the Lord’s Supper

4. the historic episcopate, locally adapted.

(p127)

It’s tight enough to define something real, but it’s still very loose. It is as minimal a base of fellowship as ecumenical movements such as the WCC. It should be robust. As the story goes, when someone episcopal was once asked about the Anglican “split”, the response was “how do you split blancmange?” Anglicanism, historically, has not been brittle.

Yet now, even the Quadrilateral, raises the problematic questions. Number 3) is pretty safe. Number 4) has been changed in its character through the provision of alternative oversight and mutually exclusive network of episcopal “recognitions.” Number 2) is far from guaranteed. And Number 1) is the crux of the issue: differing epistemologies no longer able to cushion themselves from each other by ambiguities.

Is the Anglican common ground shifting? We need to be honest about that.

Next: Part 8, Good Disagreement Between Religons by Toby Howarth

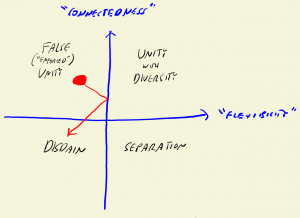

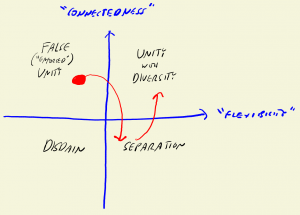

The framework loosely draws on the concepts of flexibility and connectedness. There are some marriage preparation courses that use these words to look at family of origin issues and modes of how people live together. I’m using them in a modified sense (and perhaps inaccurately) and applying them to ecclesial “family.”

The framework loosely draws on the concepts of flexibility and connectedness. There are some marriage preparation courses that use these words to look at family of origin issues and modes of how people live together. I’m using them in a modified sense (and perhaps inaccurately) and applying them to ecclesial “family.”