Review: Forming a Missional Church – Creating Deep Cultural Change in Congregations

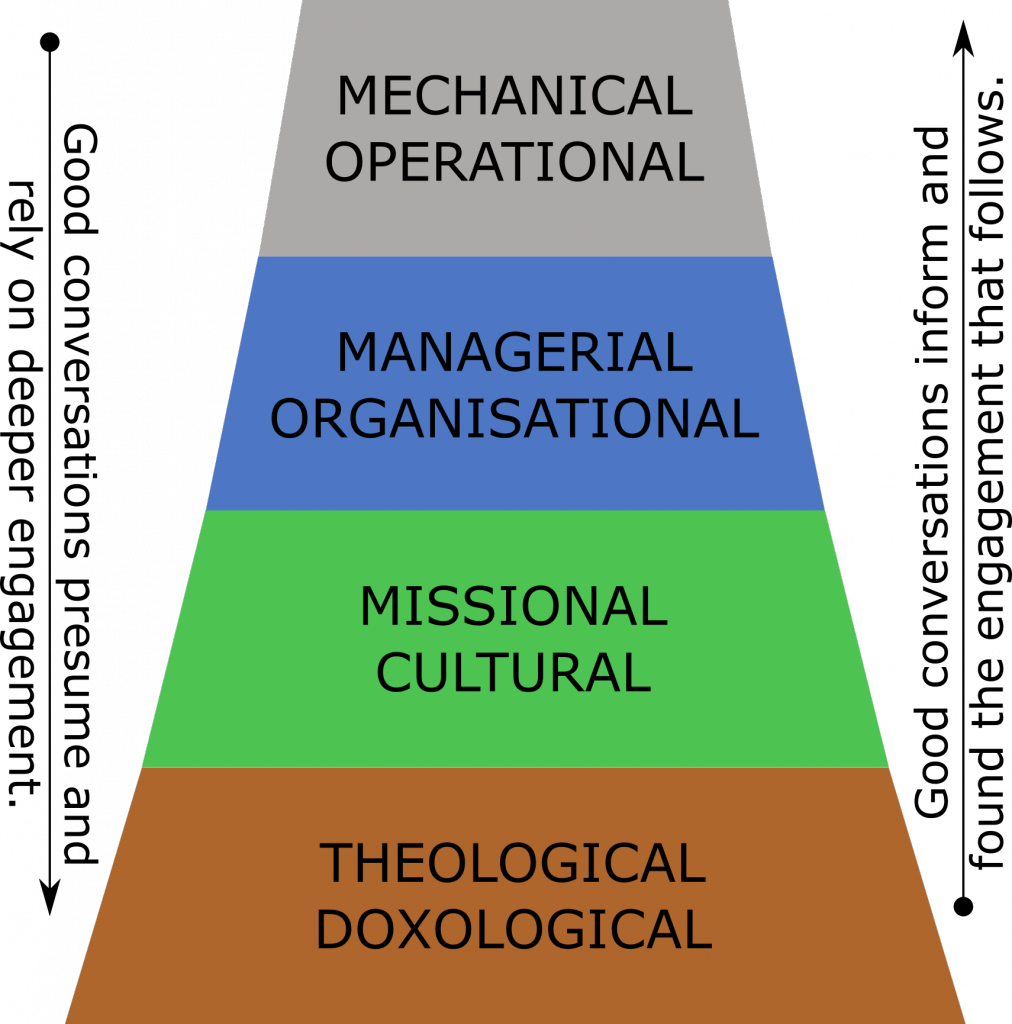

We have noticed a welcome recent trend in thinking about church life. It is a movement away from a fixation on processes and programs, traditions and techniques, mechanistic deliberations about an organisation. It is towards considering the culture of the church and understanding it as a social and familial system. It is towards recognising (perish the thought) that God the Holy Spirit is actually thoroughly and presently involved; church leadership is more a matter of sharing spiritual discernment than reliance upon managerial expertise.

We have noticed a welcome recent trend in thinking about church life. It is a movement away from a fixation on processes and programs, traditions and techniques, mechanistic deliberations about an organisation. It is towards considering the culture of the church and understanding it as a social and familial system. It is towards recognising (perish the thought) that God the Holy Spirit is actually thoroughly and presently involved; church leadership is more a matter of sharing spiritual discernment than reliance upon managerial expertise.

Two books I have recently read—Patrick Keifert’s We Are Here Now, and the Grove Booklet Forming a Missional Church which Keifert has co-authored with Nigel Rooms—do well to advance this trend and make it accessible to local congregations. The two overlap in content and I will concentrate on the Grove booklet here.

The need for cultural change is often recognised and touted albeit somewhat impotently. Rooms and Keifert seek to actually get to a practical outcome. The groundwork that gets them there takes a number of forms:

The need for cultural change is often recognised and touted albeit somewhat impotently. Rooms and Keifert seek to actually get to a practical outcome. The groundwork that gets them there takes a number of forms:

Firstly, they engage with postmodernity. Cultural connection within a postmodern world necessarily requires pushback against such modern influences as individualism, propositionalism, and didacticism. It means advancing modes and manners of being church that value real and shared experience.

The categorization of faith as private is among the reasons why many Christians do not speak and act as if God were living and active in the here and now of our every days lives. (Page 4)

This basis for their approach is not novel: the juxtaposition of church and the postmodern world has been around for at least two decades. Keifert is right not to be morose about the changing world. Rather than phrases like “post-Christendom” he prefers a “new missional era.” This obvious and positive sense only adds to my bemusement that such cultural thinking has been largely left behind in academia by church leaders in the field.

Secondly, they bring insights from systems theory. Keifert and Rooms recognise that churches like all “living, feeling, learning human organizations… are not simply machines to be fixed or problems that respond to technical solutions” (page 5, emphasis mine). Our tendency for off-the-shelf solutions makes us ill-prepared for “those challenges or problems or complicated situations for which there is not a ready or known fix.” Instead, we must attend to adaptive change.

Adaptive challenges require change and transformation on the part of those facing them, in contrast to technical problems where there is a known solution and no change is required… (Page 6)

Indeed, technical “solutions” can be used to insulate ourselves from the costly self-reflection and honesty that is necessary for the mission of the church to be taken seriously.

Our task is being born into our world, our culture and context, and dying to all we do not need to be God’s church in, but not of, the world—and then living into God’s preferred and promised future. Mission, missional life, missional churches… the missio Dei is cross-shaped. (Page 6, emphasis mine)

I have found the language of “adaptive” and “technical” to be reasonably useful as a “way in” for people to begin wrestling with the sorts of issues at stake. It is quite managerial in tone, however, and some might find liturgical or reflective language more helpful. After all, as long as the tendency to apply it only to individuals can be avoided, “adaptive” language speaks to concepts such as “being refined”, “amending one’s life”, and being “transformed by the renewing of your mind.”

Thirdly, they ground everything on robust missiology. The beginning of this is the now famous adage, which they do well to quote:

It is not the church of God that has a mission in the world but the God of mission who has a church in the world. (Page 10)

Missiology in practice emphasises the centrality of discernment in the mode and manner of being church. “We cannot simply bless every good thing” (page 11), they say, clearly understanding the propensity of churches to equate their programmatic busy-ness with effective outreach. Rather, “the main skill individuals and Christian communities require to lift anchor faithfully and sail into the unknown, adaptive, exciting, challenging journey of the missio Dei is discernment… asking and finding answers to the question, ‘What is God up to?'” (page 11). Such a journey can seem uncertain and therefore unprofessional or irresponsible for some, but from experience we know that it is, in the end, an exciting journey that is literally mission-critical:

…rather than doing mission by conducting a programme of mission activities (Alpha courses, holiday clubs for children and young people, invitational events etc), none of which are unhelpful per se, the church becomes so caught up in the missio Dei that its members are naturally ‘detectives of divinity.’ The church’s very being becomes missional so that all it is and does serves the mission of God. (Pages 11-12)

I was astounded, however, by the claim that in 2008-9 “the missiological concept of the missio Dei was only just taking hold at the level of theologically trained clergy” in the English context (page 10). It makes me aware of how ahead of the curve things have been in other less-established contexts around the world. But the fact that it is on the agenda is fruit of the Mission-Shaped Church report from 2004 (which they mention), and seminal works such as Wright’s The Mission of God from 2006. It elevates the importance of works such as these and other significant efforts (Forge Network etc.) around the turn of the millennium.

These three forms of engagement coalesce and have their natural conclusions in what it means to live and act as a church community. Clearly it also challenges some of the precious ways we have viewed leadership. The challenge for church leaders can be personal and overwhelming; it’s one thing to talk about missiological concepts in theory, or even to bring some sort of analysis to the church as an institution, but adaptive change cannot be led except by example. It means dealing with the “trap” of modernity that makes the “professional” leader “the primary basis of identity for both the community and the leader” while at the same time recognising that there is a role for “spiritual discernment, spiritual leadership” (page 13). To avoid this trap the leader must take a “personal spiritual journey, sometimes called a rule of life” (page 14) that faces and avoids “our own desire for control and certainty, especially in choppy waters” (page 15). Personally speaking, I have known the pain and frustration that comes from falling into this trap, seeking a vain fleeting peace in control and drive and avoidance, when the call is to trust God even as impotence and anxiety loom.

In the end, Room and Keifert present “six missional practices” (page 20). These should not be seen so much as steps in a recipe but practices that found and inform a “diffused innovation.” The hope is that through them cultural change might advance throughout the community while naturally responding to strengths and weaknesses and the very real human aspects that will either welcome or resist it.

dwelling in the word – a shared method of Bible that seeks to heed what God is saying in his Word, recognising that the Holy Spirit will speak in Scripture not only to individuals but through the members of the body, one to another. It sounds simple but, when taken seriously, allows a shared experience of being undone and remade by the Spirit of God through the Word of God.

dwelling in the world – involves the shared journey of listening and hearing what is happening within and around the community. It allows hard things to be heard, and undiscovered ways to be revealed. It anticipates the activity of the Holy Spirit in the real world who calls us beyond ourselves.

hospitality – is engagement beyond the community that comes neither from above or below, but both gives and receives, “taking turns hosting and being a guest” (page 22). It recognises that the best place to encounter both world and word is at the point where relationships open up. It turns us towards those “people of peace”—”friendly looking strangers”— that we often ignore, who are right in front of us, who are possibly not what we had expected or hoped, but who are open to heed and be heeded.

corporate spiritual discernment – is placed not at the beginning, but in the middle, as the shared experience of dwelling in word and world begins to develop a sense of “What is God’s preferred and promised future for our local Church?” “Who is God calling us to join in accomplishing that preferred future in our community?” (page 22)

announcing the kingdom – recognises that there is a gospel to share, and a Saviour to speak about. It is adaptive, not impositional: Putting words to the recognition of how the Spirit of Christ is already at work, it invites others to join him, and to enter into the kingdom not as some abstraction but in how he is present in the here and now.

focus for missional action – urges a further and clearer pursuit of the journey of discernment:

“Every ministry setting has more good things to do and more good things to love than any local church can rightly or well take on. Without the practise of discerning a focus for missional action, the sixth missional practice, the others lead to a kind of disorderly love and dissipation of energy and life into nothingness. St. Augustine refers to this pattern of behaviour as sin and it is a very common practice in most local churches.” (Page 23, emphasis mine)

These six applied practices require further thought on my part to fully understand how they are meant and why they are emphasised over other actions and disciplines. The groundwork on which they are based certainly matches my own experience. By laying this groundwork Rooms and Keifert have helped answer my own questions of “What is going on?” in a mission-adverse church. In the six practices they also attempt to answer the “So what” question: “So what can we do about it?” Given the veracity of their starting point, they certainly cannot be lightly dismissed. Criticial and biblical enquiry would serve to strengthen what should be strengthened, and correct what might be askance. This is something I hope to attend to at some point.

My main caution (which is not insurmountable) is this: behind these books is an ecclesial product. Partnership for Missional Church (PMC) is a church consultancy framework through which churches who want to explore these practices can “buy in” facilitation and support over a three-year process. Monetisation like this isn’t necessarily bad; it is akin to 3dm (focussing on discipleship and missional communities) or NCD which takes an inventory based approach to balanced growth. But there is a little discordance when a framework which resists a culture of faddish quickfixes is promulgated as something that literally needs a ™ symbol. Nevertheless, PMC does better than most to transcend the irony; a non-linear messy frustrating journey of discernment is not the stuff of populism. To the extent that it will play its part in the developing trend—changing culture until mission is a natural rhythm—it will do itself out of a job and, in that possibility, it would rightly be seen as a success.

I have learned that the Scottish love Scotland. And the Welsh love Wales. But do the English love England?

I have learned that the Scottish love Scotland. And the Welsh love Wales. But do the English love England?