Review: Diamond Geezers

If you want a decent overview of contemporary men’s ministry, this will give it to you.

If you want a decent overview of contemporary men’s ministry, this will give it to you.

I was lent a copy of Anthoney Delaney‘s Diamond Geezers as I’ve been focussing (somewhat) on “men’s ministry” recently. There’s no doubt about it, this is a book for men. It’s style, content, manner and demeanour shouts “men’s shed” and “man cave” with a barbaric yawp, using blokey vernacular and a mate-in-the-pub mode throughout.

The substance of the book is in the title. For those who can’t speak vernacular English, geezer is short for “a gentleman of the common type, esp. pertaining to integrity and worthy of respect.” Diamond is a superlative positive qualitative adjective. If you were to re-title this in Australian it would (with a bit of a wince at the overly-ockerness) “bonza blokes.”

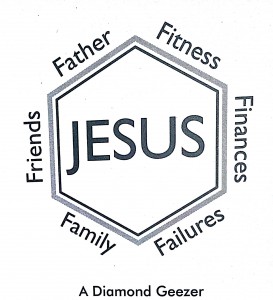

But the word diamond is quite deliberate. Delaney takes a six-faceted look at being a diamond geezer. He deals with six “f-words” which are basically an exhaustive list of the things that are found when working with men: fitness, finances, failures, family, friends and father. That is, blokes need to deal with their health issues, their wealth issues, their daddy issues, their loneliness, their relational brokenness, and their insecurities. Tying it all up is the call to live life for Jesus.

But the word diamond is quite deliberate. Delaney takes a six-faceted look at being a diamond geezer. He deals with six “f-words” which are basically an exhaustive list of the things that are found when working with men: fitness, finances, failures, family, friends and father. That is, blokes need to deal with their health issues, their wealth issues, their daddy issues, their loneliness, their relational brokenness, and their insecurities. Tying it all up is the call to live life for Jesus.

By taking this approach, Delaney has produced a robust and reasonably complete exhortation. For myself, I was prodded, provoked and prompted in the chapter on “friends.” It wasn’t just a sob story (“We’re alone too much, even when we’re with people” p99) but also had a number of challenges, including risking vulnerability, being willing to share life. Delaney avoids making it all about mush (crf. Paul who had close friends but also “knocked over fences people wanted to sit on.” p108).

Diamond Geezers aren’t afraid to get a bit closer, a bit more real. p101

In other sections Delaney does well to not just deal with the presenting issue (say on financial or physical disciplines) but to prod so that the readers realise that the issue isn’t really the issue, and that burrowing down to the root cause of pain is necessary. But it’s not always like that. Occasionally I felt that he was buying into the “be a successful man” game rather than cutting across it to encourage masculine growth in Jesus terms alone. Occasionally it’s a guilt trip, and a little bit Nike (“just do it”), which can hurt rather than help.

The value of this book is for use as a grace-aware method of communicating “let me tell you some home truths, fella.” For those blokes (and there are many of us) who simply need some sense knocked into us and to wake up to some realities, this does that with the right trajectory. For those who are wrestling more deeply, there is a chance that the gem of grace that breaks through could be encountered here, but that would be providence more than planning.

For that deeper work this book isn’t the answer, and may even frustrate. Such deeper work requires wise counsel, practical courage, and perhaps some real diamond geezers around you to help push you along. Which means, in the end, the answer isn’t this book, but Jesus working through his people. But then, that’s always the case, right? And I’m pretty sure Delaney, clearly a diamond geezer himself, would agree with that.

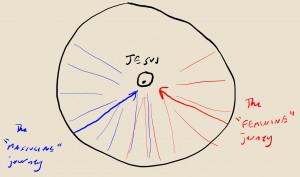

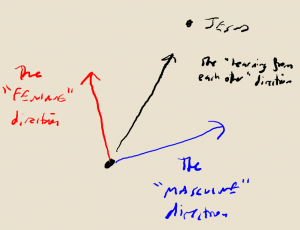

In general, men and women will grow towards Christ in different directions, like radials of a circle approaching the centre. Men and women do not absolutely need each other in order to do this, but the propensities of one, added to (not eliminating) the propensities of the other can result in a Christward direction. That’s something to work on.

In general, men and women will grow towards Christ in different directions, like radials of a circle approaching the centre. Men and women do not absolutely need each other in order to do this, but the propensities of one, added to (not eliminating) the propensities of the other can result in a Christward direction. That’s something to work on.