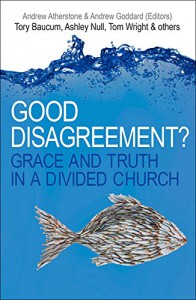

Review: Good Disagreement? Pt. 8, Good Disagreement between Religions

I am continuing with my chapter-by-chapter, essay-by-essay review of Good Disagreement? Previously:

I am continuing with my chapter-by-chapter, essay-by-essay review of Good Disagreement? Previously:

- Part 1: Foreword by Justin Welby

- Part 2: Disagreeing with Grace by Andrew Atherstone and Andrew Goddard

- Part 3: Reconciliation in the New Testament by Ian Paul

- Part 4: Division and Discipline in the New Testament Church by Michael B. Thompson

- Part 5: Pastoral Theology for Perplexing Topics: Paul and Adiaphora by Tom Wright

- Part 6: Good Disagreement and the Reformation by Ashley Null

- Part 7: Ecumenical (Dis)agreements by Andrew Atherstone and Martin Davie

To be frank I found this chapter to be frustrating. In my mind there’s two approaches to interfaith interactions: the “hide yourself” strategy, and the “generously be yourself” strategy. The first is, at its end, is a form of nihilism. The second is honest but difficult.

There is much to admire in Bp. Toby Howarth’s approach in this chapter. A generous gospel is apparent. The frustration lies in what I see to be some small, but significant, mis-steps.

Right up front, he recognises gospel distinctives and imperatives:

Some believe that religious disagreement is essentially illusory. If, they say, we could only see deeply enough and clearly enough the essentials of our superficially differing faiths, we would understand that we really all agree… My assumption in this chapter is that there is real substantial difference between religions… Not only do we believe and behave differently, many of us would like to see people from other religions change so that they believe and behave as we do, converting to belong to our faith community. (p132)

I wholeheartedly agree with this. In the aftermath of the Martin Place hostage-taking in Sydney late last year we encountered this assumption of illusion. I wrote at the time:

So when I stand in unity with my Muslim neighbours, it is not because we have been able to transcend our differences, it’s because we have found within (informed, shaped, and bounded by) our world view a place of common ground. And so the Christian doesn’t stand with a Muslim because “we’re all the same really” – no, the Christian stands with the Muslim because the way of Christ shapes our valuing of humanity, our desire to love our neighbour, and even our “enemy” (for some definition). I can’t speak for the Islamic side of the equation, but I assume there are deep motivations that define the understanding of this same common ground. Take away that distinctive and you actually take away the foundations of the unity, the reasons and motivations that have us sharing the stage right now.

The attempt to render religious differences as illusion is therefore incredibly illiberal and actually antagonistic to a healthy, harmonious, multi-religious society. I’m glad Howarth affirms this.

Similarly, Howarth’s experience are beneficial contributions to the more general “good disagreement.” In this series of reviews the importance of honesty has been mentioned a number of times. Here Howarth reminds us that this necessarily includes emotional honesty, even vulnerability and admissions of fear.

The consideration of the Non-Violent Communication (NVC) approach is therefore helpful. It “encourages people… to listen not only to others but also to their own feelings and needs” (p136). This is necessary to ensure that we are not mishearing others: I have often encountered those who are emotionally reacting against what they think my position is, not what it actually is; I should avoid doing the same. Vulnerability also puts one’s own emotional reactions out in the open, where they can be assessed and addressed. This cuts across and defuses bigotry. I attempted to reflect on this during the divisive 2012 same-sex marriage debate in Tasmania, but it was a one-sided exercise.

The current mode of good disagreement in the Church of England is the Shared Conversations process. To the extent that this achieves constructive honesty and vulnerability it’s a necessary step for good disagreement. I doubt it is sufficient for actual agreement on the issues at hand. In the short-term it may actually lead to an increase in pain, because honesty and vulnerability fully articulates the cost of a position or prospective decision. Having had one’s vulnerability fully acknowledged, and genuinely comprehended, there is no sense in which the wounds can be covered by ignorance; decisions will need to be made in full knowledge of the potential hurts.

In the interfaith scope Howarth recognises this reality; the tensions of maintaining relationship with the Hindu community in the light of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s commitment to evangelism (pp137-138) is a great example. The consequent act of maintaining relationship, even sharing meals, with the Hindu community is delightful. But it doesn’t remove the offence, it merely mitigates it. It’s a generous, gracious, neighbourly response.

The reason why good fences make good neighbours is because they protect against encroachment and thus provide a place of safety from which to be gracious. Irresolvable differences can be left in perpetual abeyance only when there is a degree of separation, as there are between religions. Unfortunately, in the current internal conflicts about Scripture and sexuality, we are dealing with conflict in the family, where there is not enough separation to prevent encroachment, and so the potential for gracious interaction is reduced.

There is therefore a degree of inapplicability of these interfaith thoughts to the current conflict. This is compounded by a few mis-steps that I think Howarth exhibits:

Firstly, he fails to avoid a false-dichotomy between story and doctrine.

Story is always present in religious disagreement. Sometimes we pretend that it isn’t… In my experience, male religious leaders are particularly prone to addressing difference in this way. We look at texts; we discuss doctrines. (p136)

His attempt at a both-and (“while this important… it often needs to be complemented” p137) reinforces story and doctrine as essentially competitive, requiring a balance. His caricature of Trinitarian presentation on page 138 may be accurate in some circumstances, but he has himself flattened the experience of doctrine. It is not enough to fill it out with reference to the historical Nicene narratives, but by the Trinitarian experiences of everyday folk in the here and now.

Doctrine fills out story and story fills out doctrine! Doctrine gives me language and understanding in which to live out my story. My story grounds my doctrine and pushes me to mull and mull until it is real and applicable. We don’t need story to balance out doctrine; we need our doctrine filled out with the real world, and our experience of the real world filled out with lively doctrine.

Secondly, he doesn’t adequately deal with the reality that it takes two to tango. What do you do in dialogue if the other side won’t talk, or won’t come to the same place of honesty and vulnerability?

I admire this sentiment:

Foundational to the different approaches that I have referred to here is a commitment to the often slow and painstaking work of developing relationships, especially by listening to the other person’s story and sharing one’s own. (p139)

But this presupposes that the other person is willing to share, and willing to listen. At what point is it inappropriate to give yourself over to another? Mark Durie, who regularly dialogues with Islam in the Australian context, considers how even generosity can be misinterpreted negatively. Similarly, there are many who see the ever-increasing illiberalism of progressive politics, and the misuse of anti-discrimination law in particular, as removing a safe-place for the sharing of a traditional point of view. I would hope that many would err on the side of risk-taking vulnerability, but how do you protect against possible entrapment?

And finally, there is the dangerous and self-defeating direction of hiding the gospel for the sake of engagement.

Howarth does not eschew Christian distinctives. He values “persuasion and conversion” (p144) and notes that “not all conflict is destructive” (p145). Nevertheless he does slip from the “generously be yourself” mode to the “hide yourself” mode.

The problem is that of the elevation of abstraction. This is when Jesus is reduced to a particularisation of an abstract gospel. For example, it is common to hear logic along the following lines: Jesus loves people, therefore we are called to love, therefore if we all love one another then your philosophy and my Christianity are essentially the same. Jesus is used as a particularisation of an abstract aspiration, in which differences are illusory. The gospel actually operates in the opposite direction: We are called to Jesus, Jesus loves (in fact, defines ultimate love), therefore we love as Jesus loves.

We see hints of this abstraction when Howarth uses Jesus to particularise the abstract desire to not “focus on dividing communities along religious lines rather than fighting the poverty and oppression itself” (p147). We see hints of it again in the exposition of the Samaritan woman when “God is present, in Christ, as the walls come down.” (p148) Jesus has become the particularisation of the abstract divinity of torn-down walls. Similarly the covenant encounter of Jacob with God in Genesis 28 (p149) is taken out of context, applied to Jacob’s later interactions with Esau in Genesis 33, and so covenantal divine encounter becomes a particularisation of abstract brotherly reconciliation.

This no mere nitpick. It’s a difference that is at the heart of cross-purposes in the current debate. One side moves from the abstract (“How do we love, accept, and include?”) and defines them by Christ (“By following him”); the other moves from Christ (“Jesus loved, accepted and included”) and absolutises the abstract (“We must follow the path of love, acceptance, and inclusion”). The difference is subtle – both mention Jesus – but substantial. In one Jesus is the goal, in the other he is simply a particular form of a larger concept. In one Jesus defines and contrasts, in the other he simply informs. Same language, different meanings. Without recognising it we cannot disagree well.

In conclusion, there are some valuable insights in this chapter. It challenged me at a number of points to examine my feelings and motivations, as well as my thoughts about such things as establishment and the role of the state in religious affairs. But in the end, there was frustration. I’m all for kenosis, and empathy, and generosity… but in the end we are still who we are, defined by Jesus, and that is the starting point of dialogue; awareness of self. If we try to examine dialogue from afar, if we confine ourselves to objectivity and mediation from the abstract, we lose our very sense of identity, and have nothing to say. And silence is very rarely good disagreement.