Review: The Day of Small Things – An Analysis of Fresh Expressions of Church…

If there was any sense in which we were once starry-eyed about the Church of England it had something to do with what we now call “fresh expressions of Church.” Gill and I were church planters once, inspired by the Mission Shaped Church report and the growing call for a “mixed economy church.” The Church of England was, from an outside perspective, a place where missiology could be lively, and the ecclesial machinery would even appoint a bishop to lead a Fresh Expressions team.

If there was any sense in which we were once starry-eyed about the Church of England it had something to do with what we now call “fresh expressions of Church.” Gill and I were church planters once, inspired by the Mission Shaped Church report and the growing call for a “mixed economy church.” The Church of England was, from an outside perspective, a place where missiology could be lively, and the ecclesial machinery would even appoint a bishop to lead a Fresh Expressions team.

The Day of Small Things is a recent report from the Church Army’s Research Unit. It’s a statistical analysis of fresh expressions (they abbreviate to “fxC”). It considers their number, their size and shape, and the manners and means of their missional and ecclesial effectiveness. It draws on over two decades of data; it is thorough and informative.

I t is an encouraging picture in many ways. The crucial role of fresh expressions in the Church of England is revealed. They may not be definitive metrics, but headline numbers such as 15% of church communities being fxC attended by 6% of the C of E populace show that the effect has been far from negligible (page 10, Executive Summary). It also indicates that much more can be done.

t is an encouraging picture in many ways. The crucial role of fresh expressions in the Church of England is revealed. They may not be definitive metrics, but headline numbers such as 15% of church communities being fxC attended by 6% of the C of E populace show that the effect has been far from negligible (page 10, Executive Summary). It also indicates that much more can be done.

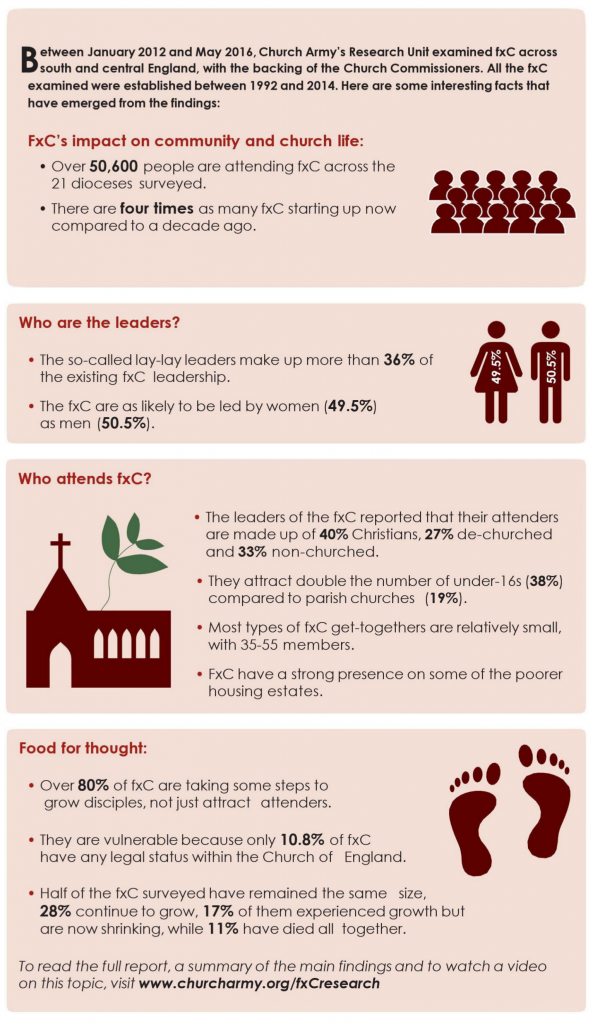

There is no need to summarise all the detail of the report here. It’s impossible to do it justice in a blog post. Church Army have, themselves, put together some excellent resources, even producing a lovely infographic (see to the side). I do, however, want to record my own observations, highlighting some of the aspects that are close to my heart and our experience:

#1 – This report helps us understand what a fresh expression actually is. On the ground, this has both a positive and a negative component.

From the negative side, I note with a growing cynicism the propensity for churches, even if well-intentioned, to borrow “off-the-shelf” language and so avoid some of the deeper challenges of mission activity. The survey invited responses from dioceses regarding activity that was classified as fresh expression and more than 40% of these activities simply had to be excluded as not only being “not an fxC” but not even readily identifiable as an “outreach project” (Section 12.10, pages 202-204).

Clearly there is confusion about the term “fresh expression”, and the excluded activities are not without value. But I share these sentiments:

We detect a disturbing tendency for increased use of any new label that becomes popular to be in inverse proportion to accurate understanding of its meaning. The same could be said for the use of the word ‘mission’ in parish and diocesan literature. It is almost now there by default, and as has been said: ‘when everything is mission, nothing is’. (Page 204)

This tendency is disturbing. In our experience, we have seen those with a heart for mission be led up the garden path towards projects and positions that were only whitewashed as such. We have seen those who would otherwise be fully on board with a fresh expression baulking at the idea because of a previous negative or insipid encounter with a project that wore the name only as a brand. Experiences such as these are damaging and stultifying.

The report, however, brings a positive initiative. In pursuing the complex and difficult work of classification of an entire ecosystem of missional actvity we are given clarity. That clarity is not simply technical, narrowly encapsulating branded programs, but reveals, in both breadth and depth, the essence of what fresh expressions are seeking to be. The discussion in section 2.4 and further development in 12.10 is worthwhile reading.

The report, however, brings a positive initiative. In pursuing the complex and difficult work of classification of an entire ecosystem of missional actvity we are given clarity. That clarity is not simply technical, narrowly encapsulating branded programs, but reveals, in both breadth and depth, the essence of what fresh expressions are seeking to be. The discussion in section 2.4 and further development in 12.10 is worthwhile reading.

The ten indicators of a fresh expression that are used as criteria for inclusion in the survey are of great value. They draw upon classifications in Mission Shaped Church and are simple observable ways of ensuring that we are talking about groups that are missional (“intends to work with non-churchgoers”), contextual (“seeks to fit the context”), formational (“aims to form disciples”), and ecclesial (“intends to become church”). Church Army have a single-page summary of the ten indicators, but a summary is worth reiterating here:

1. Is this a new and further group, which is Christian and communal, rather than an existing group…

2. Has the starting group tried to engage with non-church goers?… understand a culture and context and adapt to fit it, not make the local/indigenous people change and adapt to fit into an existing church context.

3. Does the community meet at least once a month?

4. Does it have a name that helps give it an identity?…

5. Is there intention to be Church? This could be the intention from the start, or by a discovery on the way…

6. Is it Anglican or an Ecumenical project which includes an Anglican partner?…

7. Is there some form of leadership recognised by those within the community and by those outside of it?

8. Do at least the majority of members… see it as their major expression of being church?

9. Are there aspirations for the four creedal ‘marks’ of church, or ecclesial relationships: ‘up/holy, in/one, out/apostolic, of/catholic’?…

10. Is there the intention to become ‘3-self’ (self-financing, self-governing and self-reproducing)?…

(Page 18)

A personal impact for me from this is a re-evaluation of Messy Church. I have only seen Messy Church run as an outreach project at best, often merely as an in-house playgroup. The fact that so many of the included fxC’s (close to 33%, Table 11, Page 41) were denoted as Messy Church has made me ponder them anew, especially with regards to criteria 5 to 10.

#2 – The diversity of leadership raises provocative questions. But one of the most crucial questions is absent.

Section 6.13 and Chapter 10 give the data on the forms of fxC leadership, looking at details such as gender, remuneration, time commitment, and training received. Much is as expected. For instance, male, ordained, stipended leaders predominate in traditional church plants; female, lay, volunteer leaders predominate in child-focussed fxC such as Messy Church (Table 53, page 106 and Table 74, page 176).

The report does well to highlight (in Chapter 11) the phenomenon of the so-called “lay-lay” leader who “has no centralised formal training, or official authorisation” (page 181). A leadership cohort has manifest without a clear reference to the institutional centre. I wonder how much this is a “because of” or an “in spite of” phenomenon: has the centre created space, or has it simply become ignorable? There is a gentle provocation for the institution in this:

Writers in the field of fxC have urged that the size of the mission task facing the Church of England will require many lay leaders and this is evidence that it is already occurring. The wider Church may need the difficult combination of humility to learn from them, as well as wisdom to give the kind of support, training and recognition that does not lead to any unintended emasculation of their essential contribution. (Page 189)

I note with interest that the correlation of lay-lay leadership with cluster-based churches (Chart 39, page 184) and its association with discipleship (page 187) demonstrates the crucial role of missional communities (as they are properly understood) in the development of fxC and the Church more widely.

A striking and concerning part of the data is the relative diminution of Ordained Pioneer Ministers (OPMs) with only 2.7% of fxC leaders (Table 76, page 177) being classified as such. In the seminal period of the early 2000’s, OPMS were seen as a key innovation for mission development, a long-needed break away from classical clerical formation that was perceived to produce ecclesial clones emptied of their vocational zeal and disconnected from the place and people to which they were called. Anecdotally, our experience is that missional illiteracy is dismally high amongst the current cohort of ordained persons. The traditional academy can do many good things, but the action-reflection-based contextualised formation of OPM more readily leads to the deeper personal maturation upon which adaptive leadership rests.

The absent question in the data on leadership is this: there is no recognition of couples in leadership. This is a dismaying oversight. The number of clergy couples would, I suspect, be a growing phenomenon. Similarly, in our experience, much innovative practice (particularly forms of ministry where the home or household is a key component) is led by lay couples. The Church in general, and the Anglican variant in particular, is all but inept when it comes to adequately recognising and supporting couples who lead together. It would seem to me that fxC would be the best place to explore and experiment with what this might look like. To have no relevant data, therefore, is a significant oversight. This is a topic on which I will be writing more.

#3 – Ongoing structural concerns are indicated. Structurally, fxC remain at the periphery. Moreover, while the contribution of fxC in themselves can be measured as independent units, more work needs to be done to see fxC as an integral part of the system.

The headline statistic in this regard is that 87.7% of fxC have no legal identity (Table 91, page 206). The report does well to reflect on how this increases the insecurity of the “continued existence” of an fxC. A more general point illustrates the key concern:

An analogy, designed to provoke further discussion, is that many fxC are in effect treated like immigrants doing good work, who have not yet been given the right to remain, let alone acquired British citizenship. There is active debate about whether they are to be regarded as churches or not but little to nothing is said about giving them rights and legal identity within the Anglican family, unless they can become indistinguishable from existing churches, a move which would remove their raison d’etre… We recommend that this present imbalance of so many fxC having no legal status, and thus no right to remain or not working representation, be addressed. (Page 206)

It has been an aspect of our experience that much is demanded of fxC – Success! True Anglican identity! Numbers! Money! – in order to perpetually justify institutional existence. It’s a rigged game. Existing forms of church happily, and without comment or query, lean upon legal standing, guaranteed livings, central administrative support, legacy bequests, and even the provision of curates/trainees. It has a propensity to keep them missionally infantile. Yet, without this support, are fxC unfairly expected to run before they can even crawl?

I think of the concerning admission that in some cases “numbers of fxC attenders were deliberately not reported in order to avoid parish share, on grounds that these early attenders do not yet make a financial contribution” (page 49). Even metrics like “attendance” presuppose a structural shape that may not apply, “not counting a wider fringe” (page 57) and unfairly diminishing the value of fxC.

Perhaps the report’s suggestion that a “control group of existing parishes” (page 215) be included in subsequent reports, would go some way to balancing the picture. Such a control group would at least allow a comparison. What would be even more valuable would be a way to assess integration, i.e. to consider fxC as part of a system. Two particular aspects of this that are worthy of further consideration are:

1) The nature and need of so-called “authority dissenters.” The report recognises the importance of the diocese within the ecclesial system (page 62). It also points out that “local visions for growth have always been more common that a diocesan initiative, welcome though the latter is” (page 192, emphasis mine). An “authority dissenter” is a person or office that covers and connects new initiatives into the system. Does the high level of “localness” indicate that such provision is not needed, or that it has not been forthcoming? I suspect the latter.

I have a growing sense that the deanery is the ecclesial unit that can most readily provide a covering. Chart 46 (page 194) demonstrates at least some sense of this: Current fxC that are not “in benefice” or “in parish” are far more likely to be “within deanery.” The “cluster church” fxC type intrigues me the most – 41% of these are classified as “within deanery.”

Deaneries are peculiar ecclesial creatures. When they work, they work. But they generally have limited authority, overstretched leadership, and few resources – almost the exact opposite of the three-self maturity they might want to foment! Yet they are uniquely and strategically placed between the local and the large to nurture fxC and to protect them from diminution from both above and below as we learn to “think both culturally and by area” (page 96). An exploration of how Deaneries have fitted (or could fit) into the fxC picture would be helpful.

2) The impact on sending and surrounding churches. The report does well to distinguish between the sending team, and the participation of non-churched, de-churched, and churched cohorts. A more detailed picture would be helpful in a number of ways.

Firstly, it would help inform those who are considering being a “sending church.” The cost of an fxC in terms of financial and human resources can often be readily counted. It would also be good to know how to look for benefits, and not just in terms of the kingdom contribution of the fxC itself (i.e. it’s own sense of hoped-for “success”). A sending church is also changed in its act of sending. From a stimulus to looking “outside of ourselves” through to being able to learn from the fxC as a valued “research and development” opportunity, it would good to be able to describe and measure the sorts of blessings that attend to those who generously produce the fxC.

Secondly, it would help inform those who are wary of new kids on the block, so to speak. A typical fear is that an fxC would “steal sheep” away from existing structures, and the zero-sum calculations are made. What data exists that might address these fears? Do fxC have impacts, negative or positive, on existing surrounding ministries? What mechanisms best work to allow mutural flourishing to occur?

Finally, discipleship is key. And some personal thoughts.

The correlation of fxC mortality with “making no steps” in the direction of discipleship (page 208) is well made. The “ecclesial lesson” (page 214) is a clear imperative: “start with discipleship in mind, not just attendance… it should be intentional and relational.” It seems Mike Breen‘s adage has significant veracity: “If you make disciples you will always get the church but if you try to build the church you will rarely get disciples.”

To conclude my thoughts, though, it is worth considering New Monasticism. It’s a new movement that the report has only just begun to incorporate. “Their focus is on sustaining intentional community, patterns of prayer, hospitality and engaging with mission” (page 222). But here’s the interesting part:

More often the instincts for this [new monasticism] are combined into another type of fxC, rather than existing on its own. (Page 222)

I note with interest that the type of fxC with the largest proportion of leaders that had had prior experience with fresh expressions is the New Monastic Community (48% – Table 70, Page 166). This intrigues me. As Gill and I continue to have conversations about pioneering and fresh expressions, the longings and callings that we discover in ourselves and in those we converse with, invariably sound like new monastic characteristics. Watch this space.