Moved About Asylum Seekers

The 2nd Session of the 52nd Synod of the Diocese of Tasmania met a week ago. There was a motion in my name dealing with the issue of asylum seekers. It went through formally without debate and so I thought I’d include my intended speech here.

The 2nd Session of the 52nd Synod of the Diocese of Tasmania met a week ago. There was a motion in my name dealing with the issue of asylum seekers. It went through formally without debate and so I thought I’d include my intended speech here.

Here’s the motion:

THAT this Synod,

recognising our welcome with God freely given in Christ; and

understanding the call to reflect this with justice and compassion welcome to those who are aliens and strangers (Deut 10:19); and

affirming that the membership of the Anglican Church in Tasmania includes those who have sought asylum in Australia, having fled persecution in other places,

notes with concern significantly inhumane outcomes of the Government’s asylum seeker policy and its manner of implementation; and

requests the Bishop to write to the Minister for Immigration and Border Security, urging in the strongest possible terms that the Minister:

1) follows more closely the responsibilities and commitments made by Australia under the UN Convention on Refugees; and

2) refrains from the current actions in which immigrants and asylum seekers, including children and mothers, are incarcerated indefinitely and without due process; and

3) reverses the policy decision to offer temporary second-class safety in the form of Temporary Protection Visas, rather than the true refuge of permanent resettlement; and

4) allows proper and fulsome scrutiny of the actions of the Government with regard to asylum seekers.

Christian values, offering a strong moral voice, in the midst of a volatile debate.

It is worthy mission and articulates something of the intention of this motion. Motions such as this are not history-changing events. But they do record our voice, and articulate our values, and particularly so when saying nothing is no longer an option.

This motion records our voice in the following ways:

The first section articulates why we give voice on this issue. This issue engages with our very identity as followers of Christ: we are all in need of rescue, we are all in need of the gracious welcome of God. We speak as ones who have freely received.

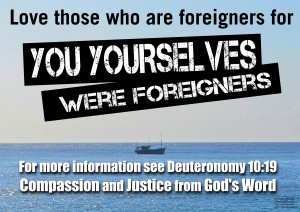

Our voice is motivated by a clear call from God to reflect that same generosity and gracious welcome. Deuteronomy 10:19 is a call to “love those who are foreigners, because you yourselves were foreigners.”

Our voice is also motivated by collegiality. We are not talking in the abstract here. Those who are affected by the debates on asylum seekers are not just fellow humans, they are not just fellow Christians, they are literally members of the Anglican Church of Tasmania, parishioners with whom we share the grace of God in fellowship and sacrament.

I, and a number of others in this room, have had the privilege of worshipping, praying, and sharing with those who have come to this land as refugees, many of them by boat. Some of them are the same age as I was when I first immigrated – six years old or younger. I see their innocence, and their parents coping as best they can in a cross-cultural context with very little assistance, and I feel for them. But then I hear threats of them being deported, or sent indefinitely to Manus Island or Nauru… And I become aware that these are not idle threats – that indeed there are around 1000 children in indefinite detention: children who are just like my brothers and sisters, and I am e-motivated. And with my voice I want to say “Do not harm my brother, my sister.”

This motion notes that current asylum seeker policy has inhumane outcomes. This is not an idle consideration.

Within the last year, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, has noted, with respect to Nauru that “the policies, conditions and operational approaches” of the Regional Processing Centre

a) constitute arbitrary and mandatory detention under international law;

b) do not provide a fair, efficient and expeditious system for assessing refugee claims;

c) do not provide safe and humane conditions of treatment in detention; and

d) do not provide for adequate and timely solutions for refugees.

A similar conclusion is made with respect to Manus Island, and forms the context in which there has been a failure to protect asylum seekers, including Reza Barati who was tragically killed in February of this year.

More recently, with reference to the Human Rights Commission’s inquiry into children in detention, the President of the Commission, Professor Gillian Triggs, spoke of the more than 300 children in detention on Christmas Island:

“The overwhelming sense is of the enormous anxiety, depression, mental illness but particularly developmental retardation,” she said.

“The children are stopping talking. You can see a little girl comes up to you and she is just staring at you but won’t communicate.”

In the light of all this, the motion asks the Bishop to exhort the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection to do the following:

Firstly, to follow Australia’s commitments under the UN Convention on Refugees. This should go without saying. It is significant that it has to be said.

Secondly, to refrain from the practice of indefinite detention of anyone, but particularly with respect to the weakest and vulnerable. The term “due process” refers not just to the process of being assessed as a refugee – which itself takes too long – but to the fundamental principle by which we rightly limit the power of the State to lock people up.

Human Rights Barrister Jessie Taylori spoke at the Opening of the Legal Year service at the Cathedral in January about mandatory indefinite detention. She informed us that under this policy, someone who has never been charged, tried, or convicted of any crime can be imprisoned for anything up to the term of their natural life. She spoke of her abhorrence as a person and as a lawyer. This motion echoes her voice.

Thirdly, the exhortation is for the minister to forgo the policy of Temporary Protection Visas. Temporary and limited refuge is not true refuge. It does not “love the foreigner” in our midst. It relegates people to an uncertainty and a restriction that prevents their life from being rebuilt.

Fourthly, the exhortation is for transparency and accountability with respect to the operation of immigration policies and the treatment of asylum seekers within Australia and in Australian-sponsored immigration centres. This exhortation is sadly needed. We have the “militarisation” of on-water activities, the prevention of the Human Rights Commissioner from visiting Nauru and Manus Island, and the abrogation of responsibilities to third countries and private companies. In the treatment of other human beings, we need to be above reproach, and this only happens by appropriate scrutiny.

I commend the motion to the Synod.