Q&A: On current political and ethical issues, why do we not hear God in the same way?

Anonymous asks:

I read with interest the series of Facebook posts sparked off by your post of the Christianity Today article. I think it is fascinating to see how Christians come to opposing conclusions from the same set of “facts”.

For me, one of the biggest problems not just in the specific case of the USA but generally, is what we mean by “discerning the mind of Christ” or “listening to the Holy Spirit”. I am fully in agreement with the article and your counter-arguments against the pro-Trump people. However, how do I know that this really is what God is saying to us?

The same can be said of other major issues on which the church is split. Each side is sure that they are listening to God. I think this conundrum is something that has got increasingly difficult over the 40 odd years of my Christian life. For example, in the early 70s, I think the evangelical world was pretty unified on the sexuality issue. We could dismiss pro-gay views as being part of the liberal wing. Now, I suspect that even the evangelical wing is probably in a minority in holding to traditional views.

Why does God not speak to everyone in the same way or rather why do we not hear God in the same way?

The Christianity Today article referenced is: We Worship with the Magi, not MAGA

[This is a Q&A question that has been submitted through this blog or asked of me elsewhere and posted with permission. You can submit a question (anonymously if you like) here: http://briggs.id.au/jour/qanda/]

Thank you for this question. This was sent in a while ago, and the delay in my response comes from the fact that this is my second attempt at answering!

Thank you for this question. This was sent in a while ago, and the delay in my response comes from the fact that this is my second attempt at answering!

At the heart of it, your question is about disagreement. In particular, it’s about Christians disagreeing on how to discern what God wants, what God wills, or simply what he is doing. In my first attempted answer I wanted to talk about epistemological differences – i.e. our understanding of how we know things – and then set our feet on the solid rock of God’s revelation in Scripture and analyse our disagreements from there.

It wasn’t a bad place to begin. From that perspective of Biblical truth we can form an opinion on whether people (including ourselves) are correct or incorrect with regard to doctrine or fact. We can also discern whether people (including ourselves) are wrong or right in terms of the spirit or character of our engagement. We can also reach for some conclusions about what things are essential or primary, and what things are secondary adiaphora on which we can disagree in unity.

On the matters you raise – Trumpism and sexuality – there has been much that has been written and said and I’m not going to rehearse it all again here. If our intention is to disagree well while holding to a robust epistemology, there are some good examples. A number of years ago I wrote a lengthy multi-part review of a book called Good Disagrement?. One of that book’s contributors, Andrew Goddard, has written very recently on the same topic of sexuality on the Psephizo blog. With regards to US politics, a recent podcast from Premier Christian Radio, Unbelievable? Is the US Church in the grip of political idolatry? with Shane Claiborne & Johnnie Moore, is useful.

The reason for my second attempt at an answer is that I think your question might be pushing a little deeper. It is a good thing to analyse the nature of disagreement. But you are asking why it happens. Why does it seem that God is not speaking clearly? If God’s truth is real and foundational, why do Christians differ so significantly on what we think that truth is? And if that clarity is not there, how can I truly know anything?

Conflict and disagreement about God’s will amongst God’s people is self-evident, biblically, historically, and in our present moment. Our trust in God cannot depend on their being a lack of disagreement. So we must find the right place for it in our thinking. To that end, I discern two types of conflict, which I will tentatively call unfaithful disagreement, and faithful disagreement.

The first category of unfaithful disagreement is needed because sometimes God’s truth is clear. The conflict arises simply because there are those who wish to be faithful to what God says, and those who wish to dismiss it, disobey it, or harden themselves to it in some way.

Many of the conflicts in the Bible are of this sort, which makes perfect sense when viewing Biblical history from the perspective of hindsight and a greater awareness of the grand scheme of things. There is story after story of various people whose eyes are open to God’s truth being opposed by those who are hardened or spiritually blinded in some way: from Cain & Abel and those who opposed Noah, through the mumbling moans of the Israelites against Moses, to Jerusalem, Jerusalem, who killed the prophets and stoned those sent to her (Matthew 23:37). This is truly the conflict of light vs darkness, truth vs lie.

These conflicts cannot be truly resolved by compromise or finding the balance of things. In such conflicts even if an “agree to disagree” can be found it resolves to a diminishment of unity, rather than an increase.

Take the issue of state authorities, for instance. With regards to Trump the normal “common ground” issues of how God ordains secular and civil leadership (e.g .in Romans 13) are not really the issues at hand. What is under dispute is whether some particular anointing, even of a Messianic kind, attaches to Trump, the nature and extent of spiritual warfare and prophetic utterances about Trump, and the intertwining of gospel proclamation with the ascendancy of one man, and the violent actions of a mob in Washington. These are matters of right and wrong, light and dark.

With regard to the issue of human sexuality; there is a lot of complexity and nuance, and things to understand and embrace in the middle of it all. Nevertheless, sometimes the dispute does encroach onto matters of fundamental clarity, and we do face (on both sides of the politics, to be honest) fundamental matters of idolatry and grossly negligent handling of the Scriptures.

To some extent, then, this answers something of your why question. Why do we disagree? Why do we claim God’s support on different sides of various debates? It is simply the human predicament: We long to stand in the light and truth of God, and at the same time our rebellious self-centred hearts oppose it. That essential conflict is therefore within society, within church communities, and even within our own souls. In our sin, we do not hear him as we should, therefore we disagree. This should not surprise us.

The response to it is hope. One day the Father of Lies will be defeated, and the One who is the Way, Truth, and Life, will shine and all will be revealed.

However, there is also a form of faithful disagreement. It rests on the reality that God made us good, and he also made us finite. There is goodness in our epistemological finitude; it is part of God’s good design that we are limited in our knowledge of the truth. Those limits are a dynamic part of us that draw us towards a deeper knowledge of God, a deeper worship.

It’s one of the reasons I am wary of Trumpist-like prophets who sometimes speak of getting a “downloaded” word from God. Biblical and personal experience, rather, indicates that God’s truth is something that we have to learn. After all, Jesus had disciples; i.e. he had students! He promised that the Spirit would lead them into all truth (John 16:13). And through the various modes of ministry and gifts within the church, a process of maturation is expected (Ephesians 4:11-13).

Some of us will know certain aspects of God’s truth differently than others. Some of us will be better versed in the Scriptures. Some of us will have had different experiences to bring alongside those Scriptures. In our learning there will be difference of opinion. But that doesn’t mean that that process of learning is flawed.

Consider the ideal: Adam & Eve walked and talked with God in their innocence; their growth and maturation sprung, in all goodness, from that relationship. (Interestingly, the fall is portrayed as an attempt to seek knowledge on their own terms). Similarly, Jesus gathers his disciples and they sit at his feet where they receive the words of eternal life (John 6:68) – and that was good! It was good when they first started being taught by him, and it was good after three years of walking and talking. And, we might note, it didn’t stop them having disputes – some of them painful – which were, in themselves, opportunities for Jesus to teach them, yet again.

At our best, this is what we see in the “disputes” of the church. They lead to greater understanding, and deeper worship. Paul talks to the Bereans and they run to the Scriptures with eagerness, (Acts 17:11), to test what they have heard. The leaders of the church come together in the Jerusalem Council of Acts 15 and they ponder together Peter’s experience with Cornelius, and the truths of the Law, and their own eyewitness learning from Christ himself, and they resolve the dispute about the inclusion of the Gentiles. They don’t pitch these things against each other to find some shallow overlap; they wrestled in their faithfulness to Scripture and the direct teaching of Jesus, in order to grasp what was happening in their experience. From this wrestle came a greater fathoming and proclamation of the gospel!

This isn’t some mystical magical thing; it’s the ordinary experience of the gospel. Personally, I remember how one of the greatest joys of my theological training was the lunchtimes debates of one topic or another – well-hearted differences of opinion that forced me back to the word of God, to wrestle, to learn, and, in the end, it led to greater worship.

Why do we not hear God the same way? Because, in his divine wisdom, our ignorance is a call to worship, as we bring each other to sit at his feet.

How, then, do we know, with the issues that are rising in our own time now, what sort of conflict we’re dealing with?

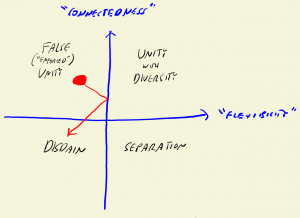

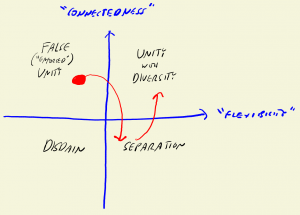

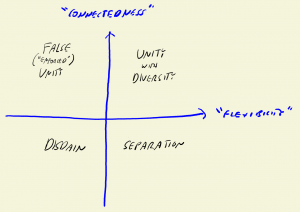

I will always do my best to take heed of the disputes around me – even the matters of Trump and sexuality. I may learn something from them, you see. Here’s the framework I use to parse that:

- Is this dispute a matter of fundamentals? Are we seeing, here, a matter of spiritual opposition to God and his word. Have we slipped from asking “What does our Lord say?” to “What am I going to say anyway?” In this case, I either call out the error as constructively as I can, or I walk from the dispute; it cannot lead me to greater worship.

- Is this dispute a secondary matter? That is, does what I have learned from God’s word stay the same on either side of the debate? I will enter into the matters if I have the inclination or energy to clarify my own opinion, but only if it’s edifying. Paul warns us away from needless controversies (Titus 3:9) and about needlessly offending our brother or sister (1 Corinthians 8:9).

- Is this dispute taking me to sit at God’s feet once more, to learn from his word, and explore his heart? At this point I will attempt to receive the dispute as a gift, even if have to expend some energy and suck up some humility. In this moment it can be a great joy and delight that we do not all hear God in the same way; there’s something more to learn from his Word.

The difficulty with the matters that you raise – Trumpism and sexuality – is that in different ways, with different people, on different particular topics, I have found that all three parts apply. Sometimes it’s a matter of opposing what is blatantly wrong. Sometimes it’s needless controversy. Occasionally it is edifying dialogue. You will see all three aspects at work simultaneously, and because of that, much wisdom is needed.

Thanks for the question.

Photo credit: Wikimedia licensed under CC SA 4.0

The framework loosely draws on the concepts of flexibility and connectedness. There are some marriage preparation courses that use these words to look at family of origin issues and modes of how people live together. I’m using them in a modified sense (and perhaps inaccurately) and applying them to ecclesial “family.”

The framework loosely draws on the concepts of flexibility and connectedness. There are some marriage preparation courses that use these words to look at family of origin issues and modes of how people live together. I’m using them in a modified sense (and perhaps inaccurately) and applying them to ecclesial “family.”