Q&A: Do we neglect the doctrine of hell?

Sarah asks:

Hi Will,

Do we neglect the doctrine of hell? I recently read Jonathan Edwards’ “sinners in the hands of an angry God” and my reaction was:

To marvel at the magnitude of my rescue;

To be reminded of the urgency of sharing the gospel and my part in that.

(I also thought you’d have to be brave to talk like that in our generation!)

I understand that Jesus spoke more of hell than heaven. Salvation is a rescue – should we talk more about the reality of hell both to draw people to the Rescuer, and to increase our worship of God and our evangelism, whilst avoiding both the Middle Ages fascination with grisly imagery and the laughed off sandwich board person proclaiming that the end is nigh. If I am honest, (and holding this alongside election) I want to belong to God to escape the horror of hell.

A related question is do we neglect the doctrine of heaven…

[This is a Q&A question that has been submitted through this blog or asked of me elsewhere and posted with permission. You can submit a question (anonymously if you like) here: http://briggs.id.au/jour/qanda/]

Hi Sarah, thanks for the question.

Hi Sarah, thanks for the question.

I must admit, I’ve never read this sermon from Edwards, (which was penned in 1741, and now available online for those who are interested). He is preaching on Deuteronomy 32:25 :- To me belongeth vengeance, and recompence; their foot shall slide in due time… (to use Edwards’ probable translation). I haven’t been able to look at it in depth, but there are a couple of things to note that can help us here:

Firstly, Edwards gets the audience right, at least initially. The text is not so much about God raging against the world, it is about God’s broken heart about his own people! Edwards describes them as “wicked unbelieving Israelites, who were God’s visible people, and who lived under the means of grace; but who, notwithstanding all God’s wonderful works towards them, remained… void of counsel, having no understanding in them.”

In this he is, indeed, reflecting the focus of judgement language in the New Testament. e.g. Jesus uses language such as “hypocrites” and John talks about “a brood of vipers”, referring to his own people. Similarly, it is the temple which will have no stone left on top of another. It is a message, first and foremost, to the people of God, including the church.

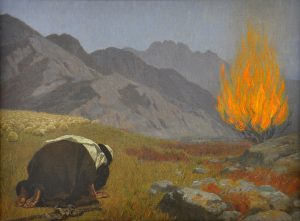

This understanding locates judgement in the midst of grace. Jesus is no Pharisee, loading down but not lifting a finger to help. No, he is the good shepherd, reflecting the heart of his Father. He has come to his intransigent people, to take responsibility for them if they would have him.

You ask “should we talk more about the reality of hell?” If we do, we need to take heed; we can’t preach judgement without going through our own refining fires. And sometimes I see a whole bunch of tinder-dry unChristlikeness amongst those who take Christ’s name. I fear it needs to be a great conflagration, and I am well and truly including myself in this brood.

Secondly, Edwards asserts that the wrath of God is real and present, withheld only by his grace, and he is right about this. This is hard for people to hear, (we are understandably uncomfortable with divine anger!), and it should always be communicated clearly. But it must be, and can be, communicated:

After all, the wrath of God is simply an aspect of his justice. It isn’t fickle, or out-of-control. It is the appropriate response to wrongdoing. We are bland and apathetic, God is not. We harden our hearts and walk past injustice, God does not. There are times we should be more angry at the unchecked sin in the world, and certainly at the unchecked sin in our own lives. The fact that there are homeless people on the streets of my otherwise middle-class town, is an injustice, it should move us. The tears of a teenager misused by her porn-addicted boyfriend, should induce something in us; a cry for justice at the least, the power to act if we can. Those who don’t want God to be wrathful shouldn’t also ask us to care about #metoo. God is not #meh about this world.

Similarly, the wrath of God is never disconnected from his righteousness and his grace. We sometimes have this image of God as someone caught in an internal battle “Do I love them, or do I hate them?” No, God is love in all things. “Making things right” through bringing justice in judgement is an act of love. Withholding judgement as an act of grace is love. When we face analogous issues – say, perhaps, in our parenting – we often experience conflict because we lack the wisdom, or the security, or, indeed, the affection to do it well. God does not lack those things.

So should we talk about these things? Yes. In fact, our current series at the St. Nic’s evening service is looking at the foundations of faith, drawing on the list in Hebrews 6:1-2 as an inspiration. “Eternal judgement” is one of the topics we will be looking at. The application will likely include those things that you mention: gratitude about the grace of God, and urgency about declaring the gospel. It will also include the imperatives that relate to pursuing God’s the Kingdom come, on earth as it is in heaven.

But your question is not just about judgement, it is about the concept of hell. And this is where you’ll probably find that I differ from Edwards. I push back at the caricature of “total eternal torment”, for I find little, if any, of it in the Bible. If anything, the exact nature of the final state after judgement, is a second-order issue for me; I won’t go to the stake for it.

My eschatology (my understanding of “the end”) looks to the renewal of this earth as the gospel hope. I’ve talked about this in my review of N. T. Wright’s excellent Surprised By Hope. Wright draws on C. S. Lewis with regards to the outcome of judgement, and speaks of a final state of “beings that once were human but now are not, creatures that have ceased to bear the divine image at all.”

Wright’s view has merit. My own take is closer to annihilationism, that the outcome of eternal judgement is either eternal life (for those in Christ), or simply ceasing to exist (you can’t get more eternal than that). I’ve written about this before, and I won’t reiterate it here.

So yes, we should talk about these things more. But here’s my final thought: You say “I want to belong to God to escape the horror of hell” and I get that. But I don’t think I would quickly, if ever, say it that way. I would say this: I want to belong to God, because he is the most holy, delightful, awe-inspiring, identity-giving, glorious One. He is my eternal Father, and I love him.

Thanks Sarah. An interesting question. Allow me to answer it generally, and then more specifically.

Thanks Sarah. An interesting question. Allow me to answer it generally, and then more specifically.