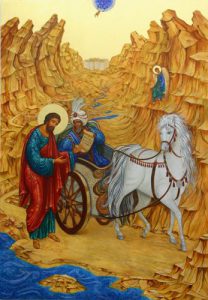

Oxford academic Emma Percy, writing in the most recent edition of Theology poses the question “Can a eunuch be baptized?“ and derives “insights for gender inclusion from Acts 8.” It’s an interesting question to pose about an interesting text. I came to the article at the suggestion of a colleague and as observation of how the thinking of the church engages (or fails to engage) with the prevailing issues of sex, gender and identity.

Oxford academic Emma Percy, writing in the most recent edition of Theology poses the question “Can a eunuch be baptized?“ and derives “insights for gender inclusion from Acts 8.” It’s an interesting question to pose about an interesting text. I came to the article at the suggestion of a colleague and as observation of how the thinking of the church engages (or fails to engage) with the prevailing issues of sex, gender and identity.

It’s a fraught topic. We are talking about a fundamental sense of “self” here. That’s a simple, hard, question: Who are you? We can inform (and hear) the answer in terms of biology, psychology, sociology or a dozen other aspects. But at the bottom of it all is one of those explorable-but-not-fathomable theological mysteries where we can get to the end of our language and risk talking at cross purposes.

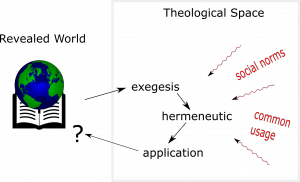

Percy’s article enters into this space. Her exegesis delivers some often overlooked aspects of Philip’s encounter on the road to Gaza and her argument extends to some good pastoral guidance. In the end, however, this essay, in itself, reveals the semantic divide that besets these issues in particular, and theological discourse in general.

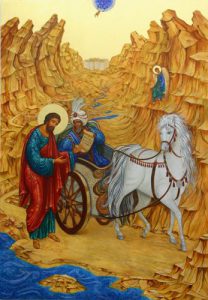

There is much to affirm. In the account in Act 8, of course, we have a eunuch. Percy emphasises the physicality of this term: the word “eunuch” applies to a person who has been castrated and it was a real phenomenon in the culture of the time. And, of course, the answer to the titular question is affirmative. In the eunuch’s own words, “‘Look, here is water. What can stand in the way of my being baptised?’”

This inclusion is kerygmatic in a profound way and Percy does well to expound it. She highlights the gospel in it: covenantal exclusion overcome, “dry branches” grafted in, those with no physical legacy drawn into the eternal family of God, etc. She is rightly incredulous: “I cannot count the number of sermons I have heard about the Ethiopian eunuch which have made no reference to the significance of his being a eunuch!”

In applying the text to the contemporary debate Percy is firstly ready to admit that “it is not appropriate simply to map the term ‘eunuch’ on to those who are intersex or transgender.” She is secondly ready to do exactly that, using the lens “of people who do not fit into neat binaries of male and female.”

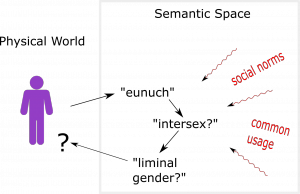

And so she brings us to consider intersex persons. The mapping is not direct: A eunuch is an emasculated male and so defined by the binary, and what has been lost; an intersex person has indeterminate sex, described by referencing variations of either end of the binary or neither. Nevertheless, for both the eunuch and the intersexed, their embodied selves don’t fit “neatly” into the sexed categories, and the gospel inclusion of the eunuch does inform our response.

Percy outlines the pastoral implications. To give just a few of her words:

The Acts 8 story itself offers an important reminder to make inclusion a priority. Baptism becomes for the Church the mark of a Christian and, unlike circumcision, it does not require a particularly gendered body. Women can be baptized and so too can those whose bodies do not conform to gender norms…

Clergy need to be aware of the pastoral needs of families with intersex babies who may want baptism before they feel they can assign a gender to their child. Registers ask for the child’s sex, but surely this is not a necessary requirement of baptism. In a culture where children are often identified as male or female by scans, even before they are born, the families of those who cannot be so neatly categorized need compassionate pastoral support.

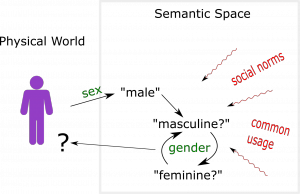

It is when she turns next to consider transgenderism that we begin to run into the semantic issues that complicate dialogue on these sorts of issues. To explain what I mean, I need to give my take on how language works in our search for meaning:

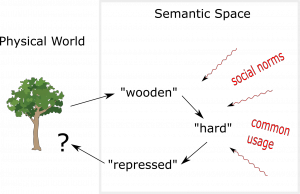

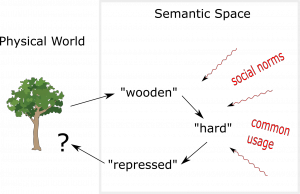

All language is ultimately self-referential, but it begins with a simple referent. An example helps: when communicating the physical reality of a tree we use a word, such as “wood.” It’s a simple syllable that refers to the physical reality of what trees are made. A simple word, a simple physical referent, a simple meaning.

In the joy that is human creativity, semantics get expanded. The fact that wooden objects are hard and rigid extends the meaning of “wood” to include a sense of hardness or immovability. By this I can describe someone’s facial expression as “wooden.” The simple word now means something additional, that is more complex and abstract.

This expansion is not a logical necessity, the expanding meaning only partially derives from the characteristics of the physical tree. In a large part, the meaning comes from convention, common usage, and social norms; the semantics of the word are at least partly socially constructed. And that construction can shift and expand even more: I could also use “wooden” to mean “rustic” or “natural.” And now a word that is objectively derived from the physical stuff of a tree can mean anything from “emotionally repressed” to “undisturbed by the advancement of modernity”!

The linguistic complexity can come full circle. The original word, applied back to the initial referent, brings its expanded meaning with it. And this is what leads to contradictions, the limitations of language, and talking at cross purposes.

The linguistic complexity can come full circle. The original word, applied back to the initial referent, brings its expanded meaning with it. And this is what leads to contradictions, the limitations of language, and talking at cross purposes.

To finish with my example: I might have in my garden a beautiful tree, that is full of life and character; the way it sways in the wind and the flowers that form on it speak of joy and vitality. In attempting to describe this I might reach for an antonym. To communicate the verve and vitality of my tree, I could say “my tree is not wooden.” Linguistically, it is a contradiction, effectively nonsense. It only communicates meaning if there is a shared understanding of semantics, agreed upon social norms that construct the sense of what that means. If two interlocutors did not share or agree on the semantic space they would be talking at cross-purposes.

It’s a simplistic illustration. It is manifoldly more complicated when we engage not with trees but with the meaning of self, our sense of identity.

In Percy’s engagement with intersex the semantic ground is relatively safe. She emphasises the physicality of the eunuch and intersex, using physical words, even anatomical ones such as “micro penis.” These words are closely connected to the simple referents of physical bodies. Her meaning, and therefore, her exhortation, is thoroughly graspable. And it should be grasped even by the most conservative reader. In the politics of it all, conservatives who throw the whole “LGBQTI” alphabet soup into the one anathematised pot, should get a bit more bothered about doing the hard yards of seeking to understand the meaning of those letters and, at the very least, take a lead from Percy’s wisdom on how to care for those who are intersex.

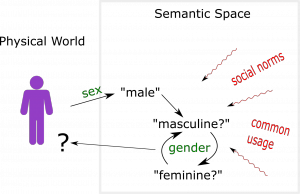

But as the consideration moves from intersex to transgender, the semantic complexity escalates; the mystery of self is manifest in the various constructions and reflections that come in the search for meaning. It can never be fully mapped out, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try. To that end, I find an important linguistic distinction between sex (as in intersex) and gender (as in transgender):

The concept of sex has a clear referent. We use words such as “man” and “woman”, “male” and “female” and they closely encapsulate physical characteristics. It’s why we use “male” and “female” to describe plugs and sockets!

The expansion of these words in a shared semantic space is an engagement with a sense of gender. Gender is more socially or self-constructed, a sense or even a “feeling” of what it means to be be male or female. We use words such as “masculine” or “feminine” to explore this meaning.

The expansion of these words in a shared semantic space is an engagement with a sense of gender. Gender is more socially or self-constructed, a sense or even a “feeling” of what it means to be be male or female. We use words such as “masculine” or “feminine” to explore this meaning.

Part of this meaning derives from the physicality of the referent sex. e.g. “masculine” might adhere to a sense of muscular dominance, or assertive impositional (some might even say “penetrative”) engagement; “feminine” might adhere to softer embrace, or fierce motherly protectiveness. But in this semantic expansion, the meaning also derives significantly from social expectation, poetic legacy, various forms of prejudice, and all the other things that you find in the shared language of a human community.

And, of course, as the semantics come full circle, those constructed meanings are applied back to the physical referent. Our language reaches its end point: We end up talking about “manly men” or “boyish girls” – linguistic tautologies and contradictions that only make sense if the social inputs into the semantic process are shared and agreed upon.

This is not just some academic exercise. The subject at hand here is a sense of self. It is how how we conceive of and find meaning in our own bodies, and locate ourselves within the millieu of meaning. Human history is full of people fighting over words (consider current controversies about the use of pronouns) and this is why: the social constructions have semantic force and so influence, even impose, on our sense of self. The cost and pain of these fights, particularly as they relate to gender, is something that I can really only observe and seek to understand:

Take for instance, the feminist movement. A certain socially normative sense of “feminine” which encapsulated notions of weakness, passivity, or intellectual inferiority, was rightly rejected. A strong contingent of unashamed women refused to agree that such semantics should inevitably, invariably, or ever at all refer to them. Through various forms of persuasion and social action the social norms were shifted (and could still shift some more) and this in turn has shifted our understanding of femininity, demolishing gender distinctions where those distinctions were meaningless or unjust, and delivering a larger degree of freedom to those who are physically female. In simplistic terms, in order to reflect a sense of self, the referent biological sex differences were strengthened (“I am strong, I am invincible, I am woman!”) and the semantic gender differences were redefined, minimised, even eliminated.

The complexity of transgenderism is that it approaches self-meaning from the other direction, beginning not with biological sex, but locating primary meaning in the sense of gender – as masculine or feminine or of neither or both senses. Semantics that derive from the physical sex are de-constructed, leaving the self-and-socially-constructed semantics as the primary source of meaning.

As this meaning is applied back into the physical world, the meaning of gender collides with its physical referent, manifesting as a disconnect between meaning and reality, and reflected in our language. The linguistic progression is this: a reference to “a man who feels like a woman” (a description) becomes semantically equivalent to “a man who is a woman” (a contradiction) becomes semantically equivalent to simply “a woman” (as a disconnected label, an arbitrary nomenclature). At this point it is entirely logical, albeit ethically perplexing, to make physicality conform to the semantic construct. In simplistic terms, in order to reflect a sense of self, the referent biological sex differences are redefined, minimised, even eliminated, and semantic gender differences are constructed and absolutised.

Much more could be said about the complexities, inconsistencies, and contradictions that this creates within a human community. Suffice it to say that I find myself exhorting for the importance of physicality. The irreversible modification of one’s body to conform with a self-and-socially-defined semantic of gender seems to me to be a fraught and ultimately unfruitful quest for meaning. It would seem to me wiser and more compassionate to affirm the complexity of the sex-gender dynamic, and embrace and include whatever we might mean by the “feminine male” or the “masculine woman” or the interwoven complexity of gender expressed constructively and joyfully in male and female bodies. I think the Scriptures have some beautiful light to shine on and guide such an exploration.

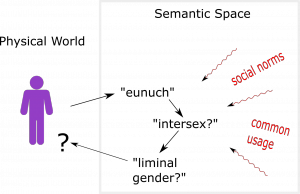

What has intrigued me, however, in engaging with Emma Percy’s article, is how the semantics of her discourse correlate closely with the semantic direction (and ultimate disconnect) of transgenderism itself. As she broadens her application of Acts 8 from intersex to transgender she buys into the semantics. Her rhetoric moves from her earlier, grounded, positive kerygma and becomes that of unanswered questions and provocative exhortations that are built upon her own theological constructs.

Even the meaning of the eunuch shifts, from the historical physicality of the Acts narrative into her own semantics of gender. The progression is clear: The eunuch’s physical referent is initially explored and carefully correlated to other physicalities, but then subsumed into a mere metaphor of “liminal gender.” Once captured into Percy’s theological world, the historical figure is is not actually needed and could quite literally (and ironically) be “cut off” from the argument.

Even the meaning of the eunuch shifts, from the historical physicality of the Acts narrative into her own semantics of gender. The progression is clear: The eunuch’s physical referent is initially explored and carefully correlated to other physicalities, but then subsumed into a mere metaphor of “liminal gender.” Once captured into Percy’s theological world, the historical figure is is not actually needed and could quite literally (and ironically) be “cut off” from the argument.

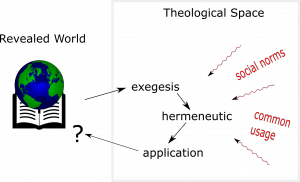

The correlation between positions taken in the gender identity debate and theological process shouldn’t surprise. It’s not for no reason that such issues have become the touchstone of theological divides!

The correlation between positions taken in the gender identity debate and theological process shouldn’t surprise. It’s not for no reason that such issues have become the touchstone of theological divides!

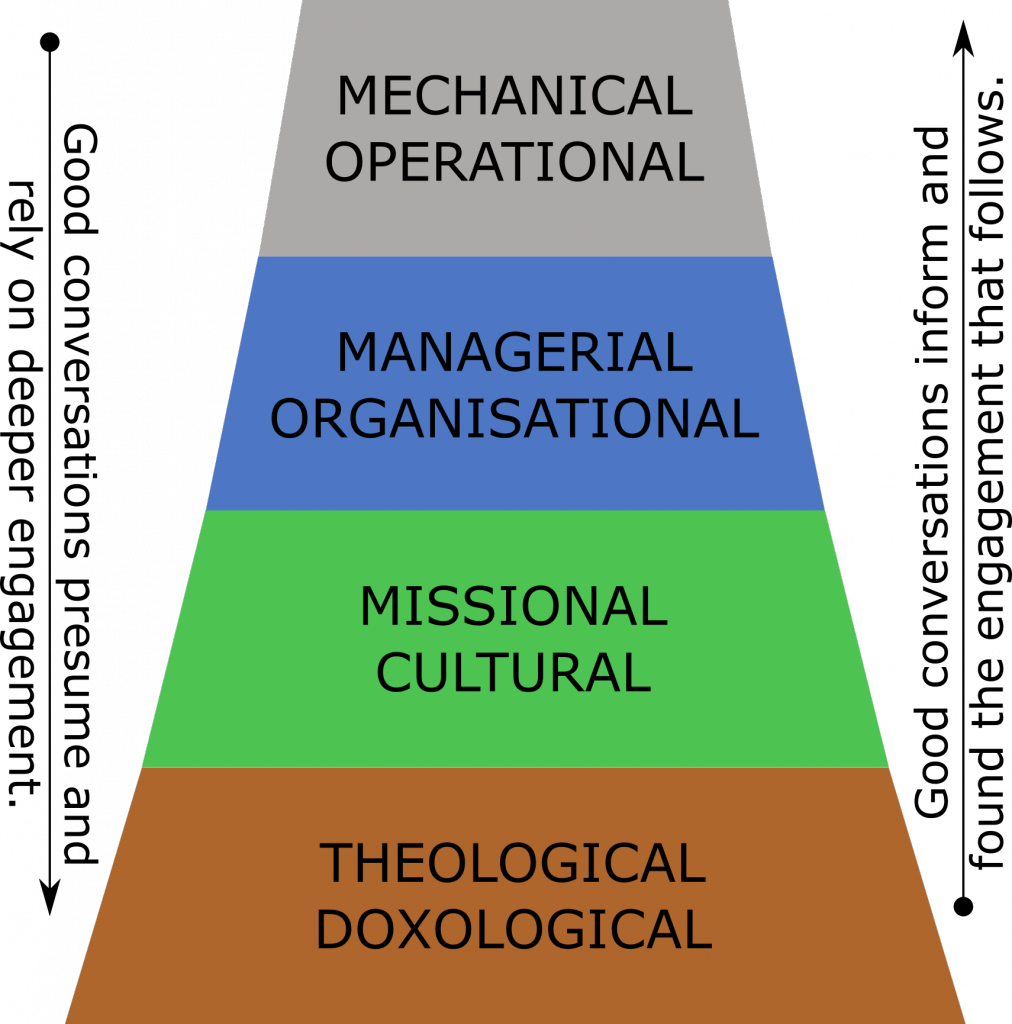

Like all quests for meaning, theological method will find itself engaging with the revealed world of Scripture and the general truths of science and common sense. Semantics and interpretation will play their part as social assumptions and hermeneutical lenses are applied. Some methods emphasise the biblical referent as the primary source of meaning. And others will look to the socially-and-self-constructed semantics. It seems to me that Percy’s framework is doing the latter, following the same semantic course as transgenderism: deconstructing the referent, and locating meaning in that which is socially-and-self-constructed. She juxtaposes ecclesial norms (marriage, baptism, the gender of Jesus) with the semantic force of gender fluidity. The hanging question and the wondering implication embraces the deconstruction.

That is not, in and of itself, a bad thing. Genuine inquiry uses the semantic space to explore mystery. There’s a lot to like in Percy’s essay and it has helped my own exploration. But it does bring to bear the issues of theological language, and whether I am understanding what Percy is meaning. Consider a word like “inclusion”, which is important enough to be in Percy’s sub-title, and which I affirm as a gospel imperative. Does Percy mean it the way I mean it? Or is it empty language which can only be inhabited with meaning if I share and agree with her constructed semantic? Perhaps the answer is simply more dialogue, but the risk of cross-purposes remains significant. The fact that I need to ask these semantic questions reveals my fear: that we are more and more a church with a shared language, but a disparate sense of meaning, with separate methods of exploring the mysteries of this world that cannot easily be shared.

The Bishop of Oxford, Steven Croft, visited us here in the Newbury Deanery this last week. He spoke and took questions in the evening at a public service and he focused, as he has since his inauguration, on the beatitudes from Matthew 5. For the rest of this week I have been mulling these over, especially the first one:

The Bishop of Oxford, Steven Croft, visited us here in the Newbury Deanery this last week. He spoke and took questions in the evening at a public service and he focused, as he has since his inauguration, on the beatitudes from Matthew 5. For the rest of this week I have been mulling these over, especially the first one: