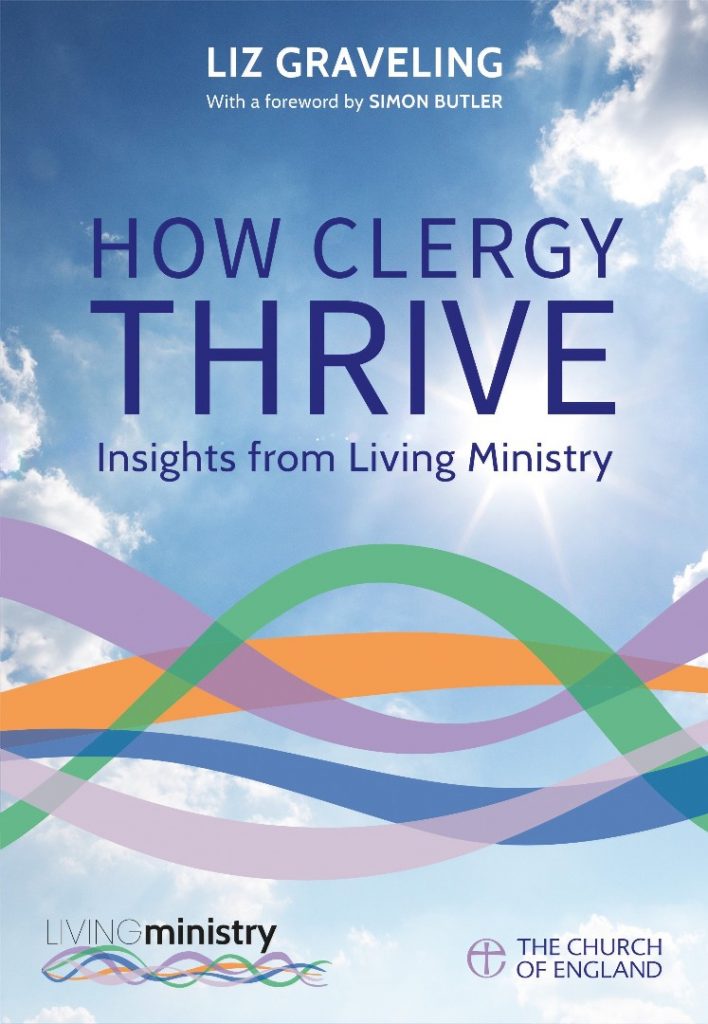

How Clergy Thrive is a short report in the Church of England that was released in October 2020. It provides insights from the Living Ministry research programme, a longitudinal study into clergy wellbeing that has been following four cohorts of clergy and their families. It is substantial research and author, Liz Graveling, presents it well. It pushes in the right direction but, unsurprisingly, falls short of a fulsome exhortation for the cultural and structural changes that are really needed.

How Clergy Thrive is a short report in the Church of England that was released in October 2020. It provides insights from the Living Ministry research programme, a longitudinal study into clergy wellbeing that has been following four cohorts of clergy and their families. It is substantial research and author, Liz Graveling, presents it well. It pushes in the right direction but, unsurprisingly, falls short of a fulsome exhortation for the cultural and structural changes that are really needed.

I have attended enough “resilience” sessions at clergy conferences to approach a report on this topic with a healthy cynicism. This report avoids many of the normal pitfalls.

For instance, clergy wellbeing is often reduced to a matter of individualised introspection and the promotion of coping mechanisms. Refreshingly, this report recognises that “wellbeing” is a “shared responsibility” (page 7). It notes that the “the pressure to be well”, itself, “can sometimes feel like a burden”. Indeed, “clergy continuously negotiate their wellbeing with institutions, social forces and other people: family members, friends, colleagues, parishioners, senior clergy and diocesan officers, as well as government agencies and market forces.” We clergy live in a complex web of ill-defined social contracts. We are often the least defended from the inevitable toxicities. A recognition of this system is a good foundation.

Similarly, the multifaceted approach to “vocational clarity” (page 9) deals well with actual reality. There is always a gap between the “calling” of ministry and the “job” of ministry, between the way in which the Holy Spirit gifts someone to the body of Christ, and their institutional identity. In my experience, the wellbeing of a clergyperson is essentially shaped by one’s emotional response to that gap. Wellbeing is encouraged by stimulating and supporting a clergyperson to reach an honest, holistic, and healthy equilibrium. It is undermined by arbitrary training hoops and merely bureaucratic forms of institutional support. The short discussion on where annual Ministry Development Reviews are either helpful or not (page 9) or even damaging (page 10) indicates that this dynamic has been recognised. The many “questions for discussion and reflection” are also helpful.

It’s impossible, of course, to read something like this without evaluating my own wellbeing and the health of the institution to which I belong. I have my own experiences, of course, including some significant times of being unwell. Here, however, my attention has been turned to the cultural and structural problems that are revealed.

Take the surveyed statement “I feel that I am fulfilling my sense of vocation” (page 11). It is noted that “79% agreed they were fulfilling their sense of vocation.” This sounds reasonable. However, I’m not sure if that positive summary is quite what the data actually suggests. Only 47%, less than half, of the respondents can fulsomely agree with vocational fulfillment. The other 32% in that 79% can only “somewhat agree”, and a full 20% is neutral or negative.

In many professions this picture might be excellent. Retention rates for teaching, for instance, indicate a 30% loss after five years.1 We must, however, make a distinction between an ordained vocation and most other professions. In ordained life, one’s profession is not just one facet of life, it is holistic (page 7); it captures many, if not all, of life’s parts. Integration of those parts is key to being healthy. How can it be, then, that 53% of our clergy are not able to fully find themselves within the life of the church? From my perspective, this speaks of a consumeristic culture in which clergy are service-providing functionaries rather than charism-bearing persons. Perhaps it simply speaks to an unhealthy culture in which it is tolerable for square pegs to be placed in round holes despite the inevitable trauma. Whatever the case, this isn’t about the church institutions doing wrong things, it’s about innate ways of being wrong; we need to change.

We see glimpses of this same sense throughout. Consider the relative benefits of the activities that are meant to support clergy (page 14). The more positive responses correlate to personal activities or activities that are outside the institution: retreats, spiritual direction, mentoring, networks, and academic study. The institutional supports such as MDRs, Diocesan Day Courses, Facilitated Small Groups and so on, are of relatively less benefit. In fact IME Phase 2, the official curacy training program, scores worst of all! I cannot speak to IME – my curacy was in Australia – but the rest of the picture certainly matches my own experience.

This is observation, not disparagement. I generally sympathise with those in Diocesan-level middle management. They have tools and opportunities that look fit for purpose, but they so often appear to run aground on deeper issues they cannot solve. Dissatisfaction then abounds. A related observation is this: It appears to me that a common factor amongst the poorer scoring forms of support is that they are often compulsory. This invariably amplifies dissatisfaction. Appropriate accountability and commitment aside, compulsion usually reveals an institution propping itself up through confecting its own needfulness.

Again, when “sources of support” are considered (page 31), the ones most positively regarded are non-institutional: family, friends, colleagues, and congregation. Senior Diocesan Staff, Theological College, and Training Incumbent score low. This is understandable and perhaps it is unfair to make this comparison; no one is expecting the Bishop to be a greater source of support than one’s spouse. However, the question wasn’t about support in general, but about “flourishing in ministry“, and the picture remains stark. Note, also, that the most negative response that could be offered was a neutral “not beneficial.” If a negative “unhelpful” were counted, the picture might be even starker.

My point is that cultural problems are being revealed. If only 63% of respondents could agree, at least somewhat, that “the bishop values my ministry” (page 49) then this is not so much a problem in our bishops, and certainly not the clergy, but in the institution in which we all embody our office.

Remuneration and finances are also revealing. 45% of the respondents are “living comfortably”, but 81% of the respondents had “additional income” (pages 39-40) which, I suspect, relates mostly to the income of a spouse. To some degree, this is all well and good; a dual income usually means a better quality of life. Nevertheless, the sheer disparity in financial wellbeing between clergy couples with one or two incomes cannot be ignored. The provision of parsonage housing is a factor; in other occupations accommodation costs generally rise and fall along with household income and dampens the disparity. More importantly, however, is how this reflects the individualisation of vocation, and the shocking degree to which clergy spouses are simply invisible, for better or for worse, within the Church of England. It is also my experience, both personally and anecdotally, that the wellbeing of couples who are both clergy is not well assisted in our current culture. This is especially so for those called to “side by side” ministry, who share a ministry context and usually only one stipend. It’s well past time to allow for couples to be licensed and commissioned as couples, like many mission agencies do. We need the means to share remuneration packages and tax liability, and, at the very least, the provision of National Insurance and pension contributions for the non-stipended spouse. Our current culture does not allow for this.

Finally, this study would do well to extend its work to take into account the effects of incumbency on wellbeing. I wonder what proportion of the respondents, given their relative “youth” in career-length terms, have reached incumbent status? Incumbency comes with a certain level of stability, power, and protection. Attached to incumbency are checks and balances on institutional power. Incumbents are more clearly party to the social contract between clergyperson and institution. Associates, SSMs, permanent deacons, and the increasing numbers of crucial lay ministers are not as well protected. They do “find themselves overlooked or under-esteemed” (page 35). The increasing prevalence of non-tenured and part-time positions in the Church of England is a structural concern that does effect clergy wellbeing. We need more work here.

How Clergy Thrive has painted a useful picture. There is scope for even more insight. The benefit of longitudinal research is that the story of wellbeing can be told over time. The testimonials in this report reflect this and are very helpful. It is unfortunate, however, that most of the data is presented as a snapshot census-like aggregation across the cohorts. An accurate picture of how wellbeing ebbs and flows as a career progresses would help us all. If we knew, for instance, at what point in their career a clergyperson is most likely to not be thriving, we could respond. If clergy wellbeing suddenly drops, or if it slowly diminishes over time, that would teach us something also.

Like the vast majority of reports, this one struggles to answer the question of “What do we do about it?” How do we help clergy thrive? In the end, it appeals to an acrostic: THRIVE (pages 56-57). It’s not bad. It’s healthy advice that I’ve given to myself and to others from time to time: Tune into healthy rhythms; Handle expectations; Recognise vulnerability; Identify safe spaces; Value and affirm; Establish healthy boundaries.

These principles are applied, to a small degree, to how the existing system might do a few things differently. In the main, however, they describe what clergy have managed to do for themselves. It’s a story of technical changes for the institution, but adaptive change for the clergy. We need the reverse of that.

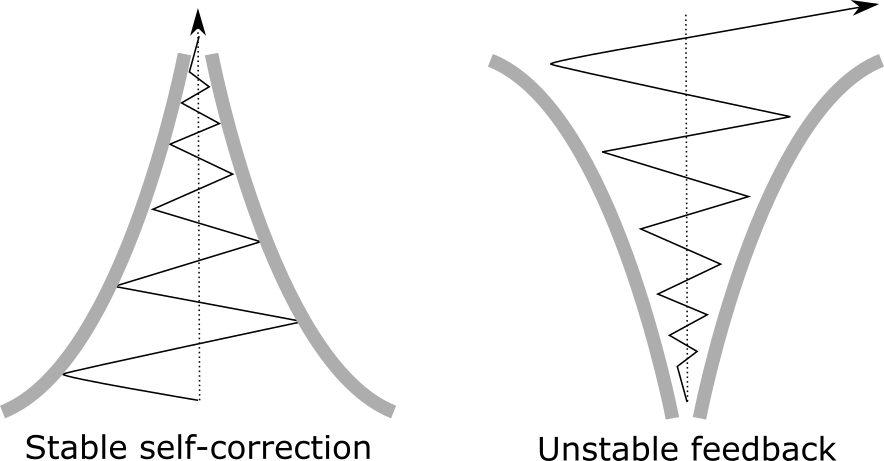

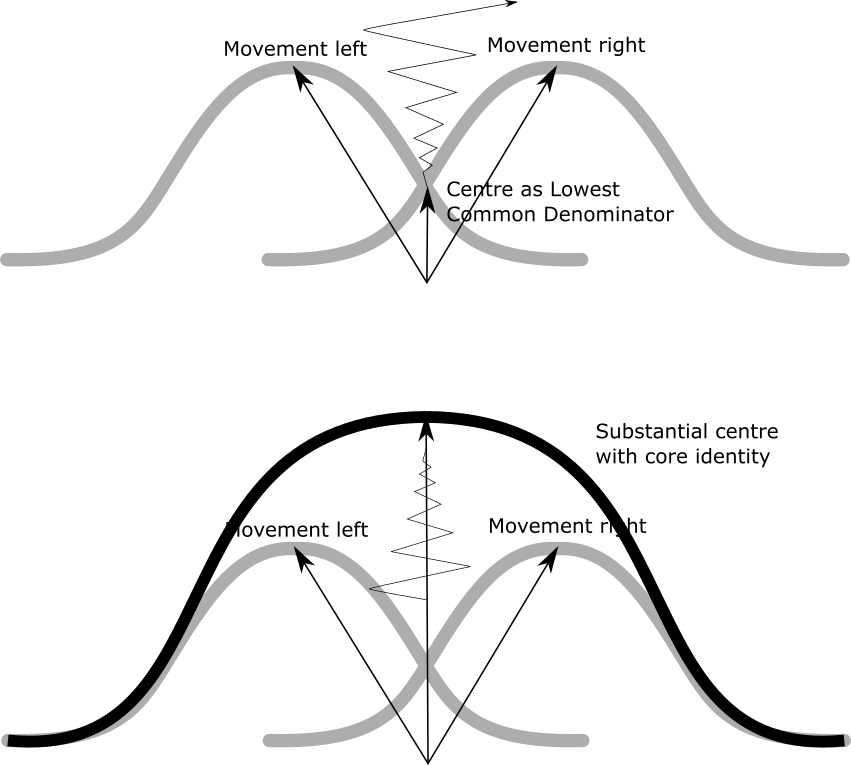

The life of a clergyperson exists in an impossibly complex interweave of pastoral, strategic, and logistical expectations. Technical changes in an institution often only add more expectation and more complexity. We have a structural problem. We have forces vectoring through things that are too old, too big, or too idolised to be modified. Instead, they are dissipated through the clergyperson, and other officeholders, but not the system itself. Personally, I’ve learned to find my place and peace with much of the machinery, and to look for the best in the persons who hold office. I have done this, in resonance with many of the testimonials in this report, by trusting real people when I can, and by not giving myself, or those I love, to the church system itself.

It’s not enough for the ecclesiastical machine to do things better. It must become different. Take heed of the testimonial on page 25 – “I wouldn’t really trust my diocese to make them aware that I have a mental health issue.” Imagine, instead, that the diocese was for that person a fount, a fallback, a refuge, or a hope! In short, imagine if the church (ecclesiastical) really aligned with being a church (theological). That’s the redemption we need. I wonder if the “big conversation” alluded to on page 6 will help.

Like most intractable problems, the hard thing is not about noting the problem. It’s not rocket science; we “just” need real Spirit-filled personal nourishment and discipleship. It’s the getting from here to there that is difficult. Difficult, but not dire. There are times when the right people are in the right place and it just works. For myself, I hold to a glimpse of how things might come to be:

What do clergy need to thrive? They don’t need an “MDR”, they need to be overseen: a regular conversation with a little-e episcopal someone who can cover them, is for them, and who has their back.

What do clergy need to thrive? They don’t need strategic plans and communication strategies, they need to be treated as the little-p presbyters they are: brought into the loop, entrusted with substantial work without being second guessed, and given space to be themselves without having to watch their back.

What do clergy need to thrive? They don’t need a “remuneration package”, they need to be provided for with decent housing that’s fit for their purpose, enough money to feed their family and prepare for the future, and an assurance that spouse and children will also be backed and supported without needing to beg or “apply.”

Footnotes

1 – National Foundation For Educational Research, 2018

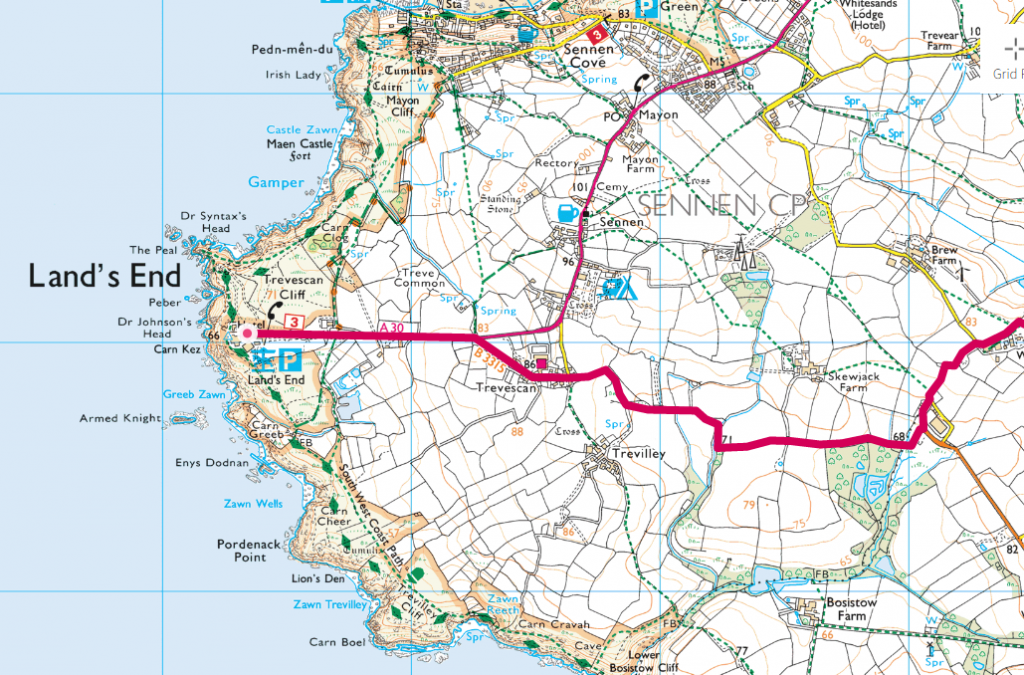

I found myself, with podcasts playing in my zoom-seasoned headphones, scanning the map of the country that I have come to call home. I “visited” Land’s End – the most Westerly point of Great Britain – and I began to ponder. How do people do that famous “LEJOG” walk, from Land’s End to John O’ Groats. What paths do they take? What does it look like?

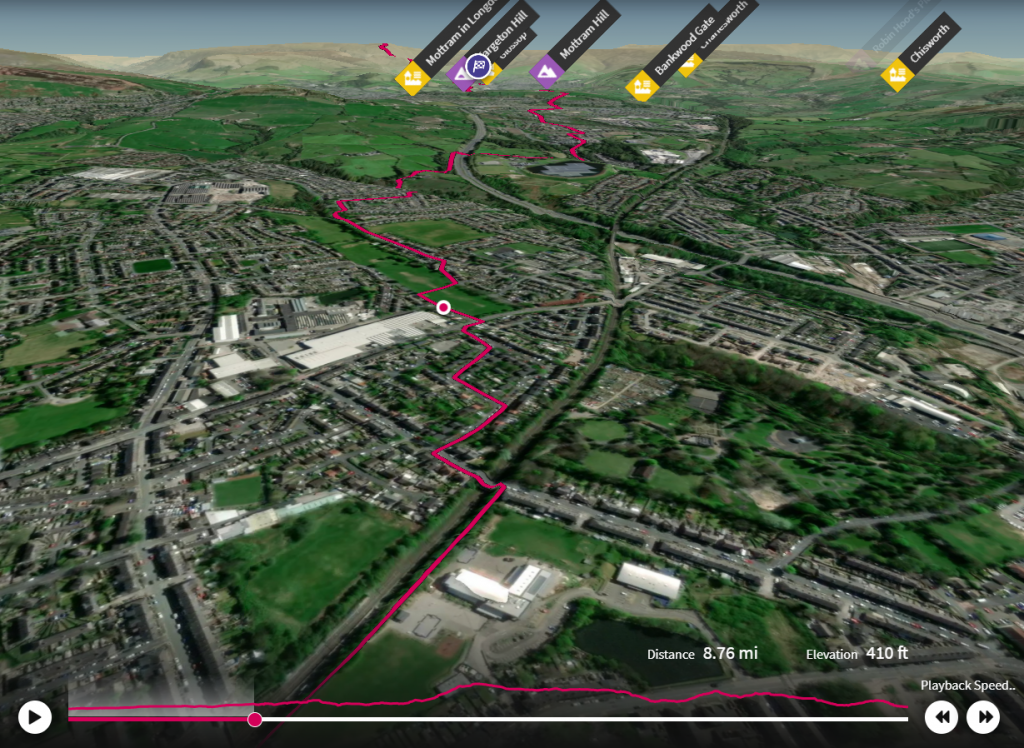

I found myself, with podcasts playing in my zoom-seasoned headphones, scanning the map of the country that I have come to call home. I “visited” Land’s End – the most Westerly point of Great Britain – and I began to ponder. How do people do that famous “LEJOG” walk, from Land’s End to John O’ Groats. What paths do they take? What does it look like? On the OS maps you can zoom right in. You can find the public rights-of-way; the green-dotted lines that give us the right to walk across fields and forests and back alleys and carparks of industrial sites. The satellite imagery lets you know if it’s paved or gravel or overgrown-tangle-of-nettles-and-brambles. You can see when the way is blocked by a river, or a motorway, a railway, or an MoD restricted zone. I began to plot a route, planning my path, imagining the place where feet might tread…

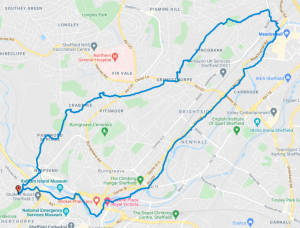

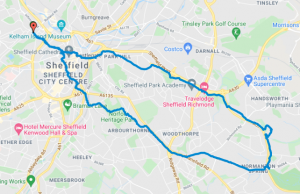

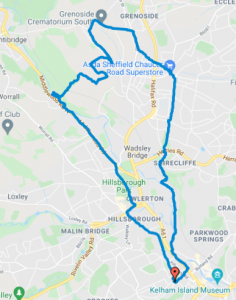

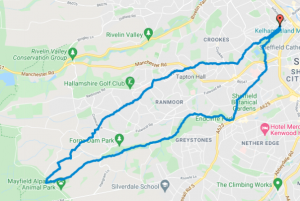

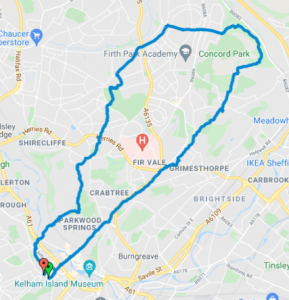

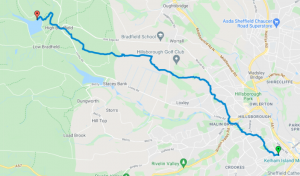

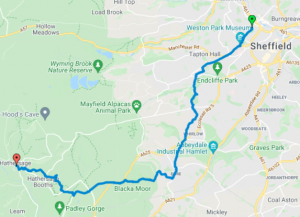

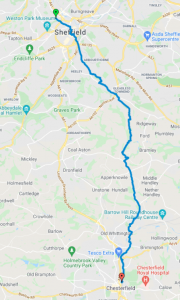

On the OS maps you can zoom right in. You can find the public rights-of-way; the green-dotted lines that give us the right to walk across fields and forests and back alleys and carparks of industrial sites. The satellite imagery lets you know if it’s paved or gravel or overgrown-tangle-of-nettles-and-brambles. You can see when the way is blocked by a river, or a motorway, a railway, or an MoD restricted zone. I began to plot a route, planning my path, imagining the place where feet might tread… But even with all the cardinal points, so much would still be missed. Praying and loving the scenery I saw (on a screen in a vicarage study in Sheffield), I found myself visiting every Cathedral in the country. It would take a zig zag up the country; two thousand miles of plotted pixels and roads to imagine.

But even with all the cardinal points, so much would still be missed. Praying and loving the scenery I saw (on a screen in a vicarage study in Sheffield), I found myself visiting every Cathedral in the country. It would take a zig zag up the country; two thousand miles of plotted pixels and roads to imagine.