Review: Good Disagreement? Pt. 1, Foreword

I have recently obtained a copy of Good Disagreement? Grace and Truth in a Divided Church. It is of current significance here in the Church of England as it informs and colours the contemporary debate about sexual ethics and gender identity in the Church. The ongoing Shared Conversations process is the current internal step for resolution, and the forthcoming meeting of the Primates in January 2016 is the last-gasp step in the wider Anglican Communion, as it currently formally exists.

I have recently obtained a copy of Good Disagreement? Grace and Truth in a Divided Church. It is of current significance here in the Church of England as it informs and colours the contemporary debate about sexual ethics and gender identity in the Church. The ongoing Shared Conversations process is the current internal step for resolution, and the forthcoming meeting of the Primates in January 2016 is the last-gasp step in the wider Anglican Communion, as it currently formally exists.

I have come to this book as someone with a deal of familiarity with the issues, but somewhat from afar. I have been following the debate since the touchstone issues of 2003 in The Episcopal Church (US). I have been involved in briefing senior figures in my former diocese with respect to the Windsor Report, Lambeth 2008, the development of the now effectively defunct Anglican Covenant, as well as the foment and formation of GAFCON and the Fellowship of Confessing Anglicans.

But I am new to the Church of England and there appears to be a deal of difference here. By my (limited and recent) observation, the rhetoric is more precise, the politics are understated, and the balance between parochial and episcopal influence is more even. The different parties exist along the spectrum here (although the edges are fuzzier) and the ability to not encroach and to live and let live runs deep… until some of the things that are held in common are touched. And then it matters. Because those common things tend to be core things.

For better or for worse, sexual ethics and gender identity is core. And so the current conflict in my mind has three different outcomes; we discern what is “really core” and resolve to move differences to the periphery and walk together; we resolve differences and either reaffirm or adjust what is core, which remains common ground; we cannot resolve our differences, which remain core, and so we agree to walk apart on different ground. In my current mind I cannot conceive how the first of these is tenable, the second would take a miracle, and the third would be regretful. To that end I admire Archbishop Welby’s resolve to sail through these waters nevertheless. I am hoping that Good Disagreement? might help plot a chart. ++Justin writes in the Foreword:

Whether each side has much or little in common with one another, whether the outcome is unanimity or separation, it seems the only way to imitate Christ in our conflicts is to invest trust, love, and time in the people from whom we are currently divided.

Could we call that grace-filled realism? Perhaps it’s just a long way of saying “speaking the truth in love”, which cannot be ad nauseaum, and does foresee an “outcome.”

Unlike other book reviews that I provide here, I am not going to reflect after the fact. I am going to consider this book chapter by chapter; it is after all a series of essays. This book will be a journey for me, and I will reflect on the journey as we go. Bon voyage.

- Part 1: Foreword by Justin Welby

- Part 2: Disagreeing with Grace by Andrew Atherstone and Andrew Goddard

- Part 3: Reconciliation in the New Testament by Ian Paul

- Part 4: Division and Discipline in the New Testament Church by Michael B. Thompson

- Part 5: Pastoral Theology for Perplexing Topics: Paul and Adiaphora by Tom Wright

- Part 6: Good Disagreement and the Reformation by Ashley Null

- Part 7: Ecumenical (Dis)agreements by Andrew Atherstone and Martin Davie

- Part 8: Good Disagreement between Religions by Toby Howarth

- Part 9: From Castles to Conversations by Lis Stoddard and Clare Hendy & Ministry in Samaria by Tory Baucum

- Part 10, Mediation and the Church’s Mission by Stephen Ruttle

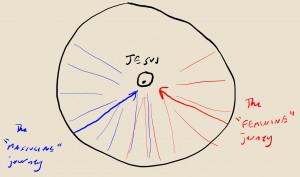

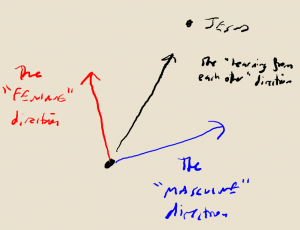

In general, men and women will grow towards Christ in different directions, like radials of a circle approaching the centre. Men and women do not absolutely need each other in order to do this, but the propensities of one, added to (not eliminating) the propensities of the other can result in a Christward direction. That’s something to work on.

In general, men and women will grow towards Christ in different directions, like radials of a circle approaching the centre. Men and women do not absolutely need each other in order to do this, but the propensities of one, added to (not eliminating) the propensities of the other can result in a Christward direction. That’s something to work on.